Supporting imagery

Models

Released on 04/03/2000 in Japan, 26/10/2000 in America and 24/11/2000 in Europe

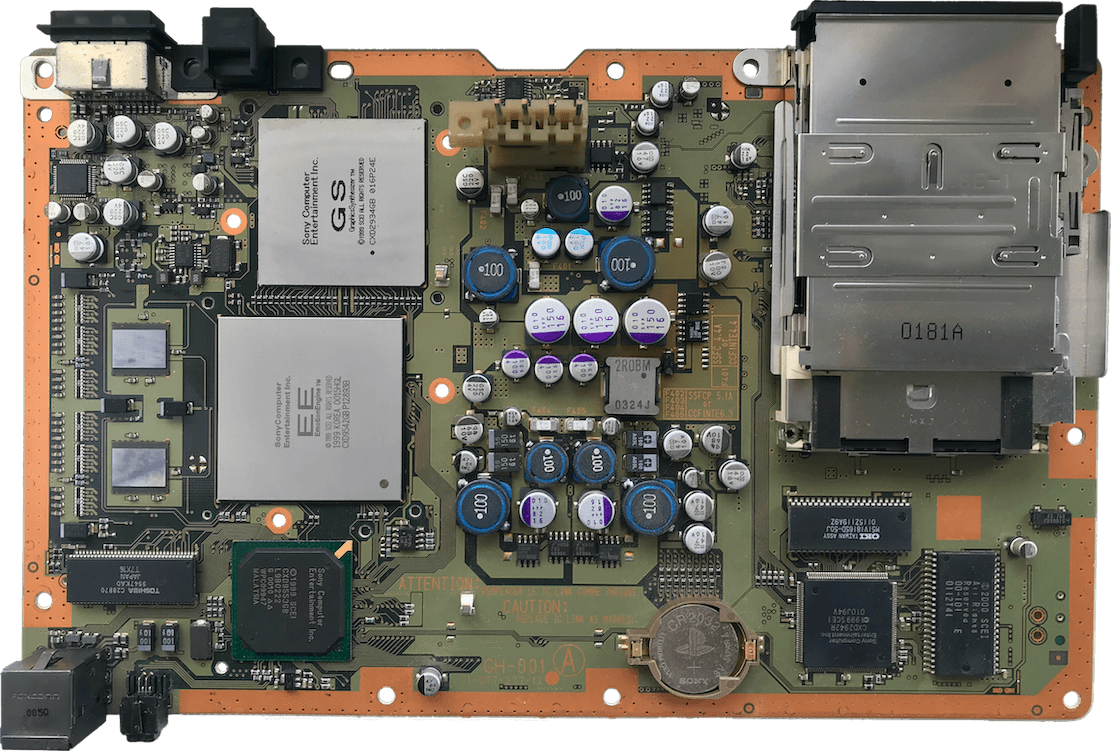

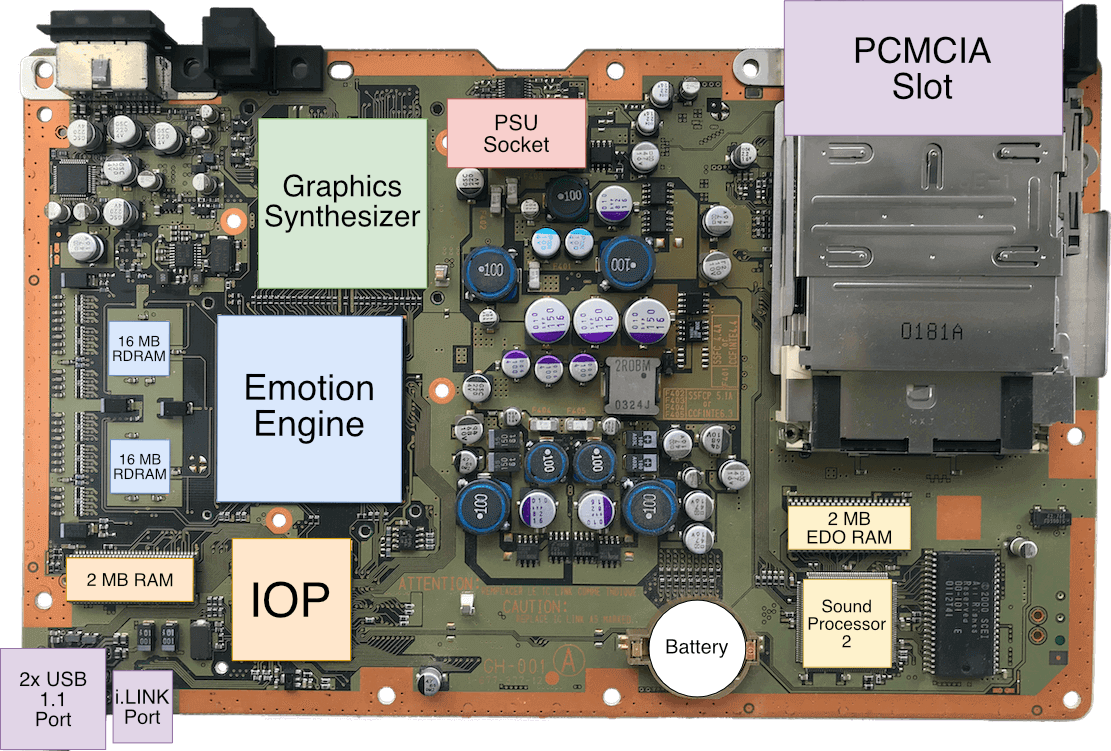

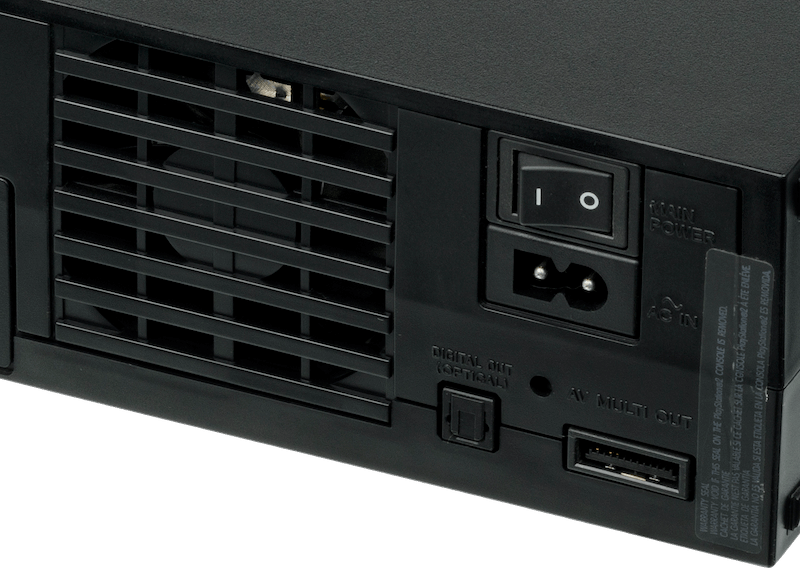

Motherboard

Showing revision 'GH-001' from model SCPH-10000 only released in Japan.

Thanks to the donations received, I was able to purchase this model and take a proper photo to allow me to identify most of the chips.

I presume the chip at the bottom right corner is the 4 MB BIOS ROM

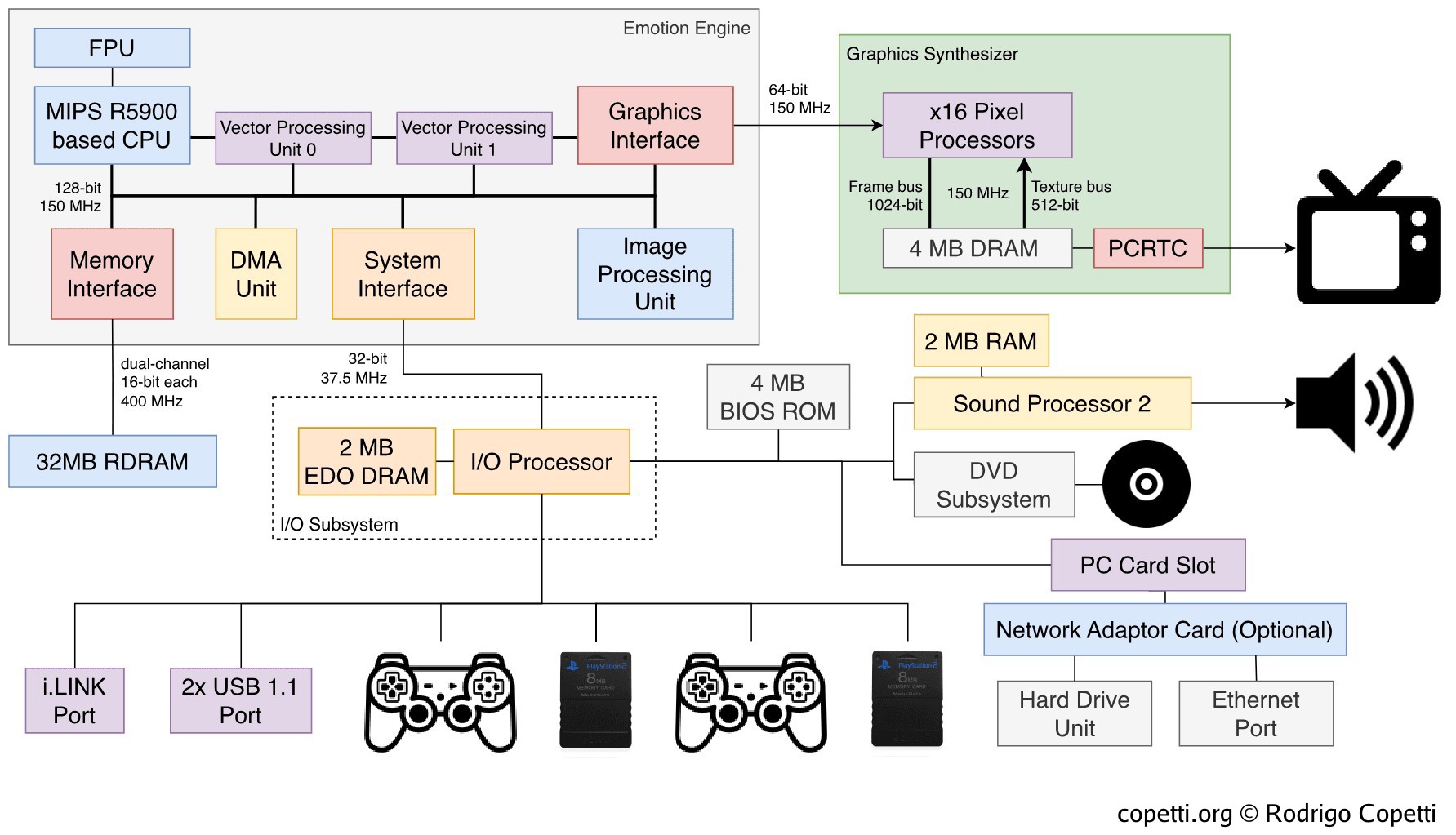

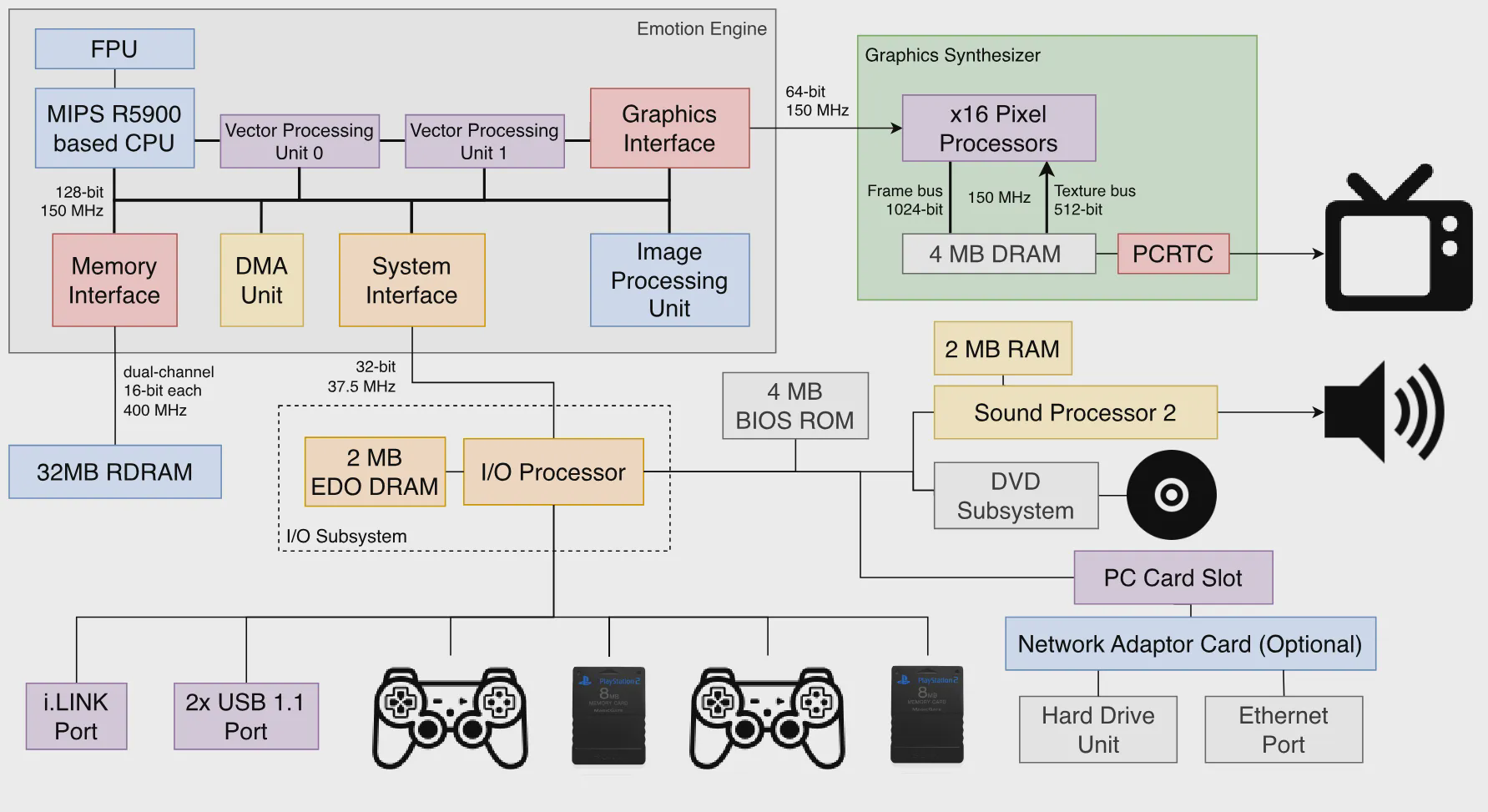

Diagram

The original design (Implemented on revision 'SCPH-10000').

Each data bus is labelled with its width and speed.

This architecture went through many revisions, more details below

A quick introduction

The PlayStation 2 was not one of the most powerful consoles of its generation, yet it managed to achieve a level of popularity unthinkable for other companies.

This machine is nowhere near as simple as the original PlayStation was, but we will see why it didn’t share the same fate as previous complicated consoles.

CPU

At the heart of this console, we find a powerful package called Emotion Engine or ‘EE’, a joint project by Toshiba and Sony [1] running at ~294.91 MHz [2].

This chipset contains numerous components, one of them being the main CPU. The rest are at the CPU’s disposal to speed up certain tasks. For this analysis, we’ll divide the EE into three sections:

- The leader: The main component that controls the entire chip.

- The memory available, a crucial ingredient so the processors can do meaningful operations.

- The co-processors: These accelerate particular computations.

The leader

In a nutshell, the main CPU is a MIPS R5900, an exclusive MIPS core designed for this console. You may recall when Sony started venturing with MIPS silicon with the very first PlayStation (where we can find a MIPS R3000A second sourced from LSI). For the next generation, we’ve got a MIPS ‘R5900’… but what does that name mean for us?

To understand what’s hidden behind the new numbers, let’s take a look at some history surrounding that era.

Outperforming success

The MIPS R4000 was a popular CPU series adopted by a wide range of systems, including a close competitor. Thanks to its success, MIPS brought a once-unaffordable range of advancements (64-bit computing, 8-stage pipelines and so forth) to the masses.

Fast forward, the next big leap arrived in 1995, with the release of the R10000. Now under the funding of SGI, MIPS produced a new processor that took the R4000’s parallelism capabilities miles further, debuting techniques like [3]:

- Speculative execution: The CPU predicts the result of conditional branches before they are computed. The predictions are based on previous results stored in an internal 512-entry table. Once the condition is computed, if the prediction turns out to be correct, the CPU has saved valuable time. Otherwise, the extra computations are discarded.

- Thanks to this, MIPS has finally turned a recurrent problem (control hazards) into an advantage.

- In other CPUs, you may find similar functionality referred to as dynamic branch prediction.

- 4-issue superscalar pipeline: On top of the pipelined design, the CPU will now fetch up to four instructions at the start of the pipeline, and distribute them across separate units, allowing the CPU to execute these instructions at the same time. In doing so, the CPU achieves a greater degree of parallelism.

- Out-of-order execution: The CPU will also re-arrange the sequence of instructions to try to fill up its units as much as possible (as long as no hazards are added).

- L2 cache with a 128-bit bus, enabling to pull more data into the CPU at a time, which becomes a requirement based on the previous enhancements.

Such innovation came at the cost of a complex design, however, and the final product was everything but cheap. SGI only bundled it in high-end equipment, and any attempt to bring it into a home console was out of the question.

High-end for the masses

Already aware of the commercial limitations of the R10000, SGI/MIPS hired Quantum Effect Devices (QED) to develop an affordable version of the R10000 for the mid-to-low-end market. As a company founded by former MIPS employees, QED was in the business of designing variants of MIPS cores for the budget sector.

In the end, QED came back with a new core called the R5000, this was an R10000 that underwent significant cutbacks [4]:

- Out-of-order execution is reverted to in-order.

- Speculative execution is removed.

- Superscalability is limited to two instructions (2-issue) and doesn’t parallelise integer instructions anymore. However, floating point instructions can still be paired with others.

- Due to the previous reductions, L2 is scaled down to a 64-bit bus instead.

Consequently, this became an ideal CPU to power economical equipment, such as SGI’s low-end workstations. In any case, notice that the cut-down pipeline still performed concurrent floating-point operations, as if QED planned to keep it an attractive product for vector/3D applications. You’ll soon see that another company quickly took note of that as well.

As a side note, it’s curious to observe that on the other side of the pond, there were similar advancements but in the opposite direction: ARM joined forces with DEC in the pursuit of lifting ARM chips into the high-end market.

A special order for Sony

Toshiba had been a MIPS licensee for some time [5] and was no stranger to manufacturing MIPS variations and packages. At one point, Sony and Toshiba joined forces to produce a CPU exclusively tailored for Sony’s upcoming console. This was a tremendous benefit for Toshiba: very often CPUs are required to fulfill a wide range of requirements coming from different stakeholders, and in doing so it constraints opportunities for specialisation. Now, there was only a single purpose: 3D gaming. Thus, granting enough room for all kinds of innovation.

That being said, Toshiba ended up grabbing the affordable R5000 design and tweaked it to accelerate vector operations. The new core is called R5900 and debuts the following ‘3D’ enhancements [6]:

- A variation of the MIPS III ISA. This includes the original 64-bit ISA previously seen on the Nintendo 64, but extended with interesting opcodes. Sony added some instructions from MIPS IV (prefetch and conditional move) along with their own SIMD extension called multimedia instructions to accelerate vector calculations (similar to the SH-4, but integer only).

- The multimedia instructions are still 32-bit wide but can operate up to three 128-bit vectors at a time. They offer operations such as vector arithmetic, min/max and many kinds of scalar combinations to form new vectors.

- 32 128-bit general-purpose registers: Another significant Toshiba-branded enhancement. Forget about the typical 32-bit storage, we’ve stepped into the 128-bit realm now. Nevertheless, the majority of operations will hardly use all the available space (MIPS words are still 64-bit long). This is when the aforementioned multimedia extension comes into the equation, as its set will make full utilisation of the extended register file.

- When using the new instructions, each register can store vectors made of many types of scalars (from two 64-bit integers to sixteen 8-bit ones).

- To prevent performance penalties, these registers are accessed through a 128-bit bus, while the rest of the CPU uses an internal 64-bit data bus.

- Two 64-bit ALUs. Each can operate 64-bit integers independently, but also combine to become a 128-bit ALU. The latter is the brain behind those shiny multimedia opcodes.

Aside from these, we also find other improvements that developers may welcome as well:

- 6-stage pipeline: That’s one additional stage compared to the predecessors.

- 2-way superscalar execution: Thanks to the two ALUs, up to two 64-bit integer operations are now executed in parallel.

- This restores another lost advantage of the MIPS R10000.

- 24 KB L1 cache: Divided into 16 KB for instructions and 8 KB for data.

- The circuitry also implements a prefetch function to cache instructions and data before they are requested. This is done by including extra logic that can identify which places in memory are more often requested.

- 16 KB of Scratchpad RAM, also known as ‘Fast RAM’.

- Memory management unit: Interfaces memory access with the rest of the system.

Moreover, the core is complemented with a dedicated floating point unit (identified as ‘COP1’) that accelerates operations with 32-bit floating-point numbers (also known as floats in C). This is a peculiar block as it doesn’t follow the IEEE 754 standard, most evident with its absence of infinity (computed as 0 instead) [7]. Apart from that, it features 32 32-bit registers.

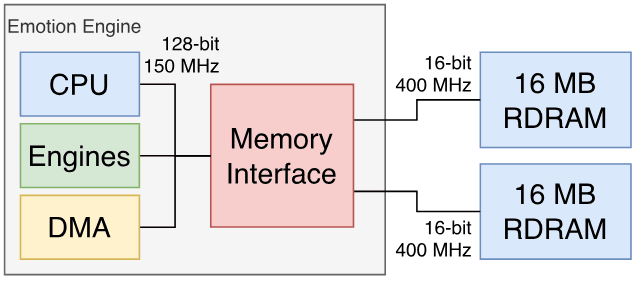

A recognisable memory choice

Next to the Emotion Engine are two blocks of 16 MB of RAM, giving a total of 32 MB of main memory. The type of memory used is RDRAM (déjà vu!) which is accessed through a 16-bit bus.

At first, this can be a little disappointing to hear, considering the internal bus of the Emotion engine is as wide as 128 bits. However, the RAM chips are strategically placed by following the dual-channel architecture, which consists of connecting both chips using two independent 16-bit buses (one bus per chip) to improve data throughput. The resulting setup provides a theoretical 3.2 GB/sec, so rest assured that memory latency is not an issue in this console!

At one corner of the Emotion engine there is a powerful DMA Controller or ‘DMAC’ that transfers data between main memory and Scratchpad; or between main memory and any component inside the EE.

Data transfers are done in batches of 128 bits, but here is the interesting part: Every eight batches, the main bus is temporarily unlocked. This leaves a small window to perform other DMA transfers in parallel (up to ten) or let the CPU use the main bus. This modus operandi is called slice mode and is one of the many modes available on this DMA unit. Bear in mind that while slice mode reduces stalls on the main bus, it does so at the cost of slowing down the overall DMA transfer.

Preventing past mishaps

Whether we want it or not, with the amount of traffic happening inside the Emotion Engine, this design will eventually suffer the consequences of the Unified memory architecture or ‘UMA’. That is: multiple independent components trying to access main memory at the same time, causing congestion. Well, to correct these issues, Sony alleviated the constant need for memory by:

- Wrapping their processors with lots of cache. Thus, only requiring access to main memory if it’s absolutely necessary.

- 99% of cache/scratchpad mentions in this article will be for this reason.

- Adding a 128-byte Write Back Buffer: Very similar to the Write Gather Pipe, but instead of waiting until it’s 25% full, it will check the state of the bus (i.e. congested or free) first.

This sounds very convenient for applications that can benefit from cache, but what about those tasks, such as manipulating Display Lists, which shouldn’t use cache at all? Luckily, the CPU provides a different memory access mode called UnCached, which only uses the Write Back Buffer. Thus, it will not waste cycles correcting the cache (product of cache misses).

Furthermore, the UnCached accelerated mode is also available. This one adds a buffer for speeding up the reading of continuous addresses in memory.

Other interesting bits

Inside the same Emotion Engine package, there is yet another processor called Image Processing Unit or ‘IPU’, this time designed for image decompression. As the successor of the MDEC, the IPU can be useful when a game needs to decode an MPEG2 movie without jamming the main CPU.

Long story short, the game sends compressed image streams to the IPU (hopefully using DMA) which are then decoded in a format that the GPU can display. The PS2’s operating system also relies on the IPU to provide DVD playback.

Finally, the IPU also operates compressed High-resolution textures, which saves CPU usage and reduces large transfers.

Co CPUs

It’s been two years since the rivals presented their latest offering. If you read the former article and just started reading this one, I presume you are still waiting for ‘the thing’ that makes the PS2 as powerful as it seemed back then. Now, let me introduce a very important set of components Sony fitted in the Emotion Engine, the Vector Processing Units or ‘VPU’.

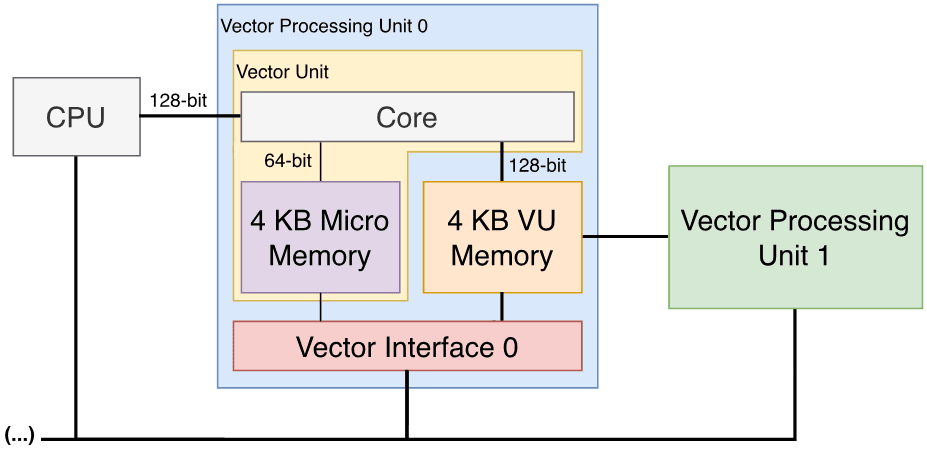

Architecture

A Vector Processing Unit is a small independent processor designed to operate vectors, in particular, vectors made of four floats. These processors are so fast that they only spend one cycle per operation, which can be extremely convenient for geometry processing. Though they exhibit similar unstandardised behaviour to the CPU’s FPU.

VPUs are made of the following components:

- Some Vector Unit Memory or ‘VU Mem’: Used as a working space for the Vector unit. It stores values needed to be operated and/or the results of previous operations.

- A Vector Unit: The core of the processor. It contains some memory (called Micro Memory) to store a program (called Microprogram) which instructs the unit on how to operate the data found in ‘VU Mem’.

- It implements a 64-bit ISA and the execution unit is split into two parallel sub-units. The first one multiplies or adds floats, while the other one divides floats or operates integers. This enables to operate both floats and integers concurrently.

- A Vector Interface: Automatically decompresses vertex data coming from main memory in a format the Vector unit can understand. This unit can also transfer microprograms to Micro Memory.

Functionality

To start working, the vector unit needs to be ‘kickstarted’. For this, the main CPU is in charge of supplying the microcode.

There are two VPUs fitted in the Emotion engine, but they are arranged differently, giving way to different uses and optimisations.

Vector Processing Unit 0

The first VPU, the VPU0, is positioned between the CPU and the other vector unit (VPU1). It provides an ‘assisting’ role to the main CPU.

The VPU0 has two modes of operation:

- Micromode: This is the ‘traditional mode’. The VPU will independently execute ‘microinstructions’ from a microprogram stored in Micro memory.

- Macromode: The VPU0 becomes the ‘COP2’ of the main CPU and executes ‘macro-instructions’, received from the main CPU through a dedicated 128-bit bus.

- Macro-instructions have the same functionality as microinstructions but use different opcodes. Nonetheless, the VPU execution unit is no longer split (meaning it can only execute one instruction at a time).

- While this mode doesn’t make full utilisation of all the components of the VPU0, it still speeds up the CPU’s vector operations. Moreover, in terms of simplicity, a co-processor is easier to program than an independent unit (something PC programmers will find helpful).

The memory map of the VPU0 also has access to some of the other VPU’s registers and flags, presumably to check its state or quickly read the results of some operations done by the other VPU.

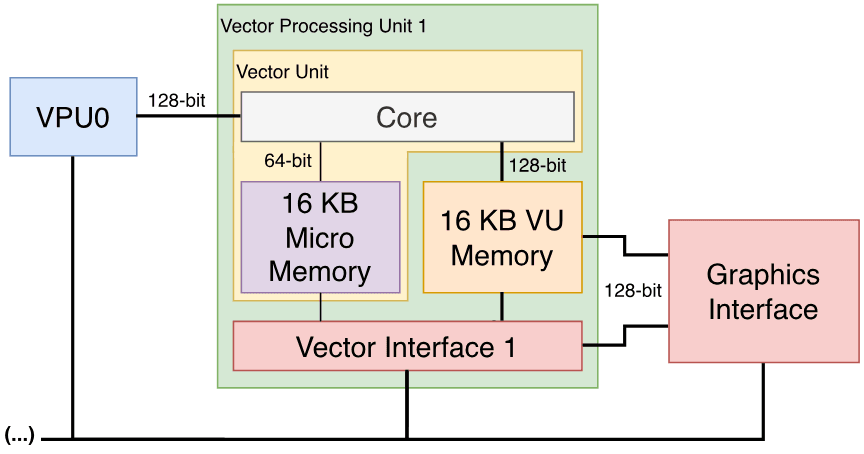

Vector Processing Unit 1

The second VPU found, the VPU1, is an enhanced version of the VPU0 with quadruple the amount of micro memory and VU memory. Moreover, this unit includes an additional component called Elementary function unit or ‘EFU’ which speeds up the execution of exponential and trigonometric functions.

The VPU1 is located between the VPU0 and the Graphics Interface (the ‘gate’ to the GPU), so it includes additional buses to feed the geometry to the GPU as quickly as possible and without using the main bus.

On the other side and due to its location, the VPU1 only operates in micromode.

It’s obvious that this VPU was designed for trigonometric operations, and may serve as a pre-processor for the GPU. Hence, it’s often put in charge of delivering the famous Display Lists.

Infinite worlds

A useful approach that can be exploited with these units is procedural generation. In other words, instead of building the scene using hard-coded geometry, let the VPUs generate it using algorithms. In this case, the VPU computes mathematical functions to produce the geometry which is then interpreted by the GPU (i.e. triangles, lines, quadrangles, etc) and ultimately used to draw the scene.

Compared to using explicit data, procedural content is ideal for parallelised tasks, it frees up bandwidth, requires very little storage and it’s dynamic (programmers can set parameters to achieve different results) [8]. Many areas can highly benefit from this technique:

- Complex surfaces (e.g. spheres and wheels).

- World rendering (e.g. terrains, particles, trees).

- Bézier curves, a very popular equation in computer graphics used to draw curves. These are turned into a Bézier patch (explicit geometry) and support different degrees of precision based on the level of detail required.

On the other side, procedural content may struggle with animations and, if the algorithm is too complex, the VPU might not generate the geometry at the required time.

To sum up, procedural rendering is not a new technique, but thanks to the VPUs, it opens the doors to further optimisations and richer graphics. Nonetheless, is not a simple technique to implement and Sony R&D published various papers describing different approaches to use on their console [9].

You define the workflow

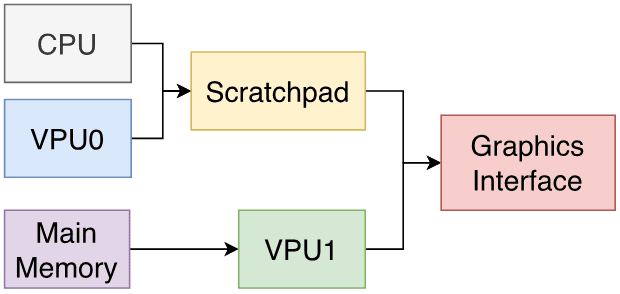

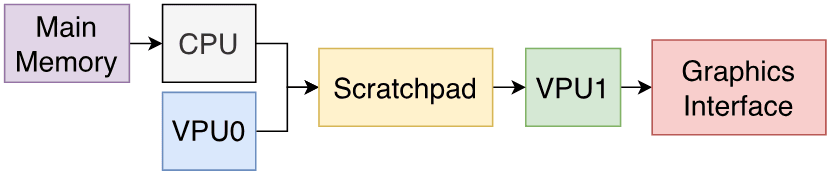

With these new additions, programmers now have a lot of flexibility to design their graphics engines. To assist with this, Sony spent additional resources to devise and document efficient pipeline designs. The following are examples of graphics pipelines optimised for different types of workloads [10]:

In the first example, the Parallel design, the CPU is combined with the VPU0 in macromode to produce geometry in parallel with the VPU1. The CPU/VPU0 group makes full utilisation of scratchpad and cache to avoid using the main bus, which the VPU1 relies on to fetch data from main memory. In the end, both rendering groups concurrently send their respective Display Lists to the GPU.

The second example, the Serial design, proposes a different approach where the CPU/VPU0 group works as a preprocessor for the VPU1. The first stage will fetch and process all the geometry that the VPU1 will subsequently turn into Display List.

These have been so far examples from the theoretical point of view, but to explain a more ‘practical’ implementation, I’m going to refer to a video Jon Burton published regarding the development of one of their PS2 games [11].

The former director of Travellers Tales explained how his team achieved a particle system fully encapsulated within the VPU1. In a nutshell, the VPU1 focused on reading a pre-populated database from its VU memory, the database was used to calculate the coordinates of particles at any given time without depending on any other component. The result of the operation could be transformed into Display Lists and sent right away.

With this approach, the CPU was significantly offloaded, allowing it to carry out other tasks like AI and physics.

There are many more examples out there, but to sum things up: It is now up to the programmer to find the optimal setup, and that, is a good thing.

Graphics

Considering all the work done by the Emotion Engine, is there something left? The last step actually: Display!

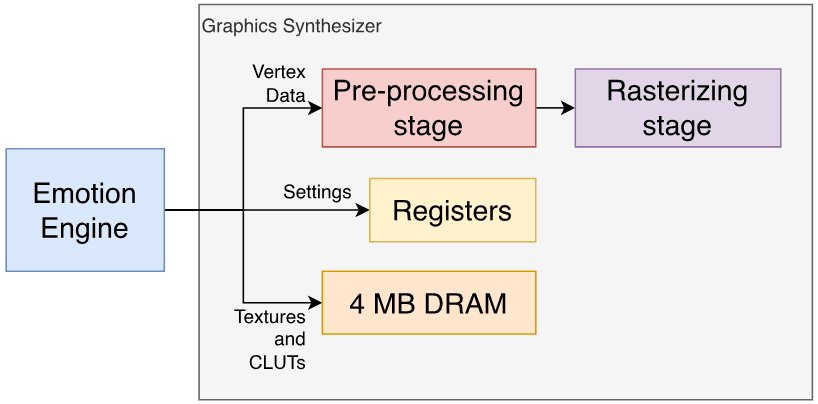

There’s a simple but speedy chip specialised in that: The Graphics Synthesizer or ‘GS’ running at ~147.46 MHz. It contains 4 MB of DRAM embedded inside to do all processing in-house. Thus, removing the need to access the main memory. The embedded RAM (eDRAM) is connected using different buses depending on the type of data needed.

The GS has fewer features than other graphics systems previously reviewed on this site. Nonetheless, it’s very fast at what it does.

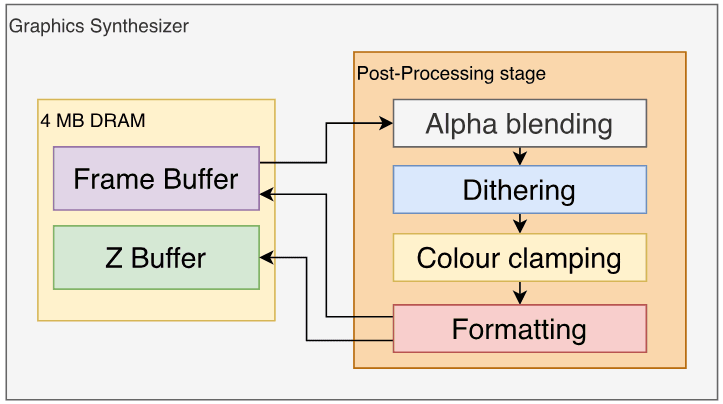

Architecture and design

This GPU only does rasterisation and that is… Generating pixels, mapping textures, applying lighting and some other effects. This means there are no vertex transformations (these are covered by the VPUs). Also, this is a fixed-function pipeline, so no fancy tweaking or shaders either, you are stuck with a fixed shading model (e.g. Gouraud).

Looks pretty simple right? Well, let’s dive deeper to see what happens at each stage.

Pre-Processing

The Emotion Engine kickstarts the Graphics Synthesizer by filling its embedded DRAM with the required materials (Texture bitmaps and Colour Lookup tables, the latter are also known as ‘CLUT’), assigning values on the GS’s registers to configure it, and finally, issuing the drawing commands (Display Lists) which instruct the GS to draw primitives (points, lines, triangles, sprites, etc) at specific locations of the screen.

Additionally, the GS will preprocess some values that will be needed for later calculations. Most notably, the Digital Differential Algorithm value, which will be used for interpolations during drawing.

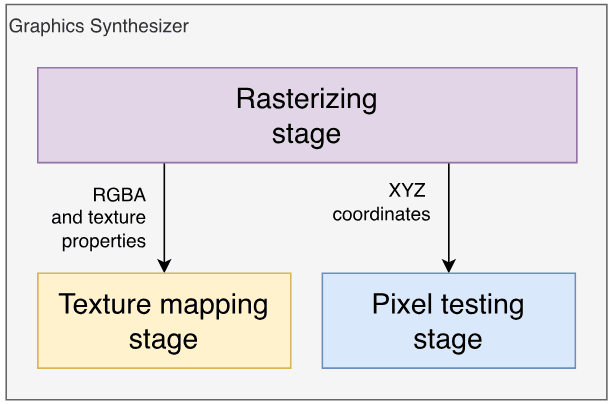

Rasterisation

Using the previous values calculated, the renderer generates pixels from the primitives. This unit can generate 8 pixels (with textures) or 16 pixels (without textures) concurrently, each pixel entry contains the following properties calculated:

- RGBA: Corresponding to the gradient of Red, Green, Blue and Alpha (transparency).

- Z-value: Used for depth testing in later stages.

- Fog: Optional, to simulate fog in the environment.

- Texture properties: Contains the address of the texture in DRAM and other properties (coordinates, level of detail, filter, etc) that will be used in the next stage.

It also performs Scissoring Tests to discard polygons outside the frame area (based on their X/Y values), some pixel properties are forwarded to the ‘Pixel testing’ stage for further checks. Lighting is also provided by selecting one of the two choices available, Gouraud and Flat.

The pack is then delivered to the ‘Texture mapping’ engine, but each property is operated by a specialised ‘sub-engine’, which enables to process of different properties in parallel.

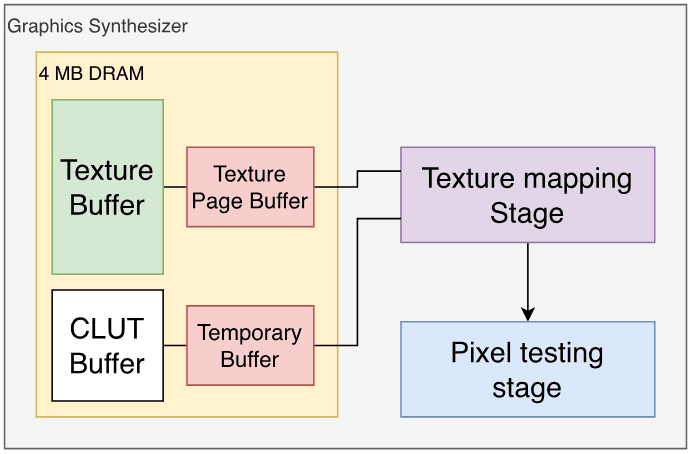

Texturing

This stage is powered by a large Pixel Unit that can compute up to 16 pixels at a time, here textures will be mapped onto the polygons (now pixels). Furthermore, fog and anti-aliasing effects are applied here.

Texture maps are fetched from DRAM in an area defined as Texture buffer, although this is interfaced by a separate area called Texture Page Buffer which seems to serve as a caching mechanism for textures. CLUTs are also mapped using this page system. Both elements are retrieved using a 512-bit bus.

The pixel unit performs perspective correction to map textures onto the primitives (a great improvement considering the previous affine mapping approach). Moreover, it also provides bilinear and trilinear filtering, the latter one is used alongside mipmapped textures.

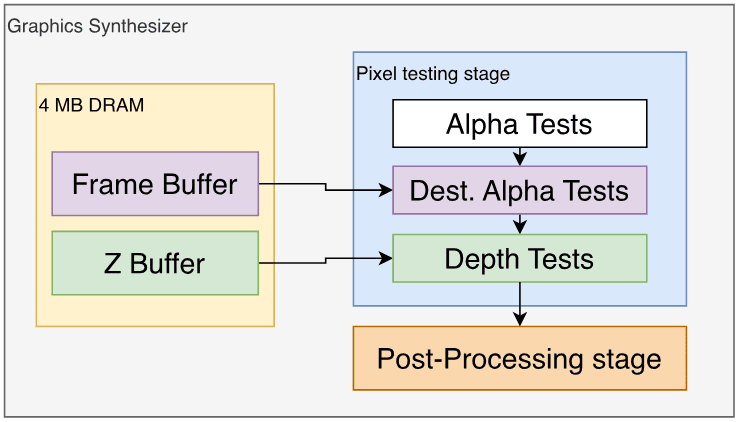

Testing

Here certain pixels will be discarded if they don’t meet several requirements. Having said that, the following tests are carried out:

- Alpha test: Compares the alpha value (transparency) of a pixel against the ‘standard’ value. This is because in some cases, the alpha value is required to be within a certain range or greater/less than an arbitrary value.

- Destination Alpha test: This checks the pixel’s alpha value again before drawing it to the frame buffer.

- Depth Test: Compares the pixel’s Z-value against the corresponding Z-value in the Z-buffer. This avoids processing pixels that would be hidden behind other pixels.

Post-Processing

The last stage can apply some effects over our new pixels using the previous frame-buffer found in local DRAM:

- Alpha Blending: Merges colours of the current buffer with the previous one in memory.

- Dithering: Large RGBA values will need to be trimmed, so dithering can be applied to soften the loss of precision.

- Colour Clamping: After applying operations like Alpha Blending, the new RGB value may exceed the valid range (0-255), so clamping sets the value within the range.

- Formatting: This converts the final frame-buffer generated in the pipeline to a format that can be stored in memory.

Finally, the new frame-buffer, along with the updated Z-buffer, are written to memory using a 1024-bit bus.

Even more post-processing

There’s a dedicated component inside the GS called Programmable CRT Controller or ‘PCRTC’ which sends the frame buffer in memory to the Video output, so you can see the frame on TV. But that’s not all: It also contains a special block called Merge Circuit that allows to alpha-blend two separate frame buffers (useful if games want to reuse the previous frame to form the new one). The resulting frame can be outputted through the video signal and/or written back to memory.

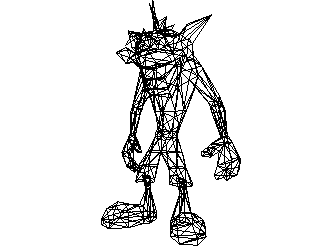

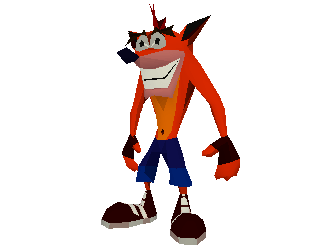

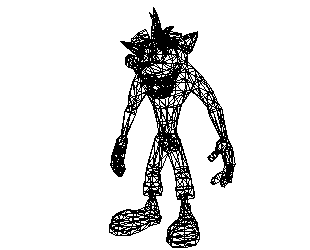

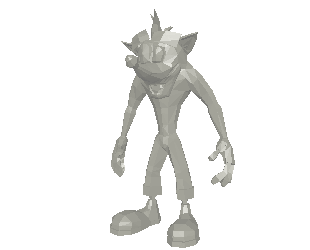

Better models

With all being said, this surely brought better designs to refresh already-famous characters. Take a look at this ‘Before & After’:

Interactive model available in the modern edition

Interactive model available in the modern edition732 triangles.

Interactive model available in the modern edition

Interactive model available in the modern edition2226 triangles.

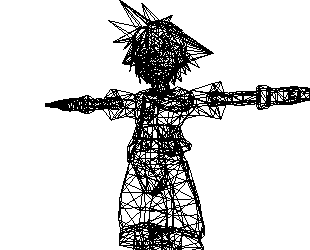

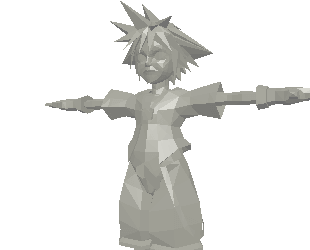

Here are characters from new game series, these were modelled with high levels of detail from the ground up:

Interactive model available in the modern edition

Interactive model available in the modern edition2744 triangles.

Interactive model available in the modern edition

Interactive model available in the modern edition2700 triangles.

It’s worth mentioning that games like Dragon Quest implemented a custom lighting model called Cel Shading (a term I have mentioned before), however, in my previous articles I explained that the GPU was mainly responsible for this. In the PS2 case, the required colour calculations are presumably done by the Emotion Engine, since the GS isn’t as flexible as other GPUs.

Video Output

As stated before, the PCRTC sends the frame buffer through the video signal. The interface can broadcast video using a wide range of formats (to work with TVs from any geographical region) [12]:

- PAL: Sends up to 640x512 pixels at 50 Hz, either progressive (576p) or interlaced (576i).

- No games found in the market use 576p. While some support progressive mode, they do so in 480p mode.

- NTSC: Up to 640x448 pixels at 60 Hz, either progressive (480p) or interlaced (480i).

- VESA: Up to 1280x1024 pixels.

- DTV: Up to the enormous amount of 720x480 pixels in progressive mode or 1920x1080 in interlaced mode.

- By tweaking the PCRTC settings, a game can also force to output in 1080p. However, this mode is undocumented and therefore subject to unpredictable behaviour.

- Does that mean the PS2 can ‘display HD’? Technically… yes, but I don’t think most game studios risked the performance penalty for a format that wasn’t popularised yet.

There’re quite a lot of modes to choose from, but it all comes down to the format adoption during the early 2000s, which narrows it down to PAL and NTSC. Also, even though PAL provided a higher resolution than NTSC, some European versions of NTSC games resorted to letterboxing to mask the unused horizontal lines and slowed down the refresh rate to fit in the 50Hz limit (I call these ‘bad ports’!).

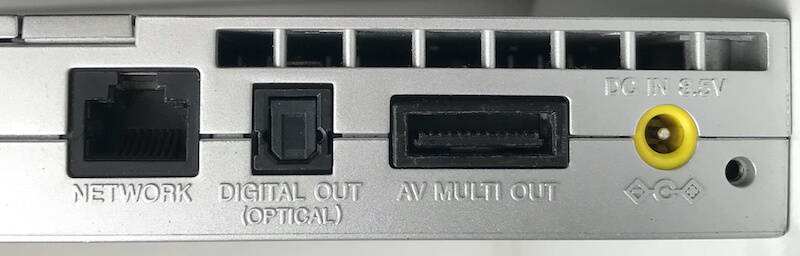

The video-out port (Multi A/V) is very convenient. It carries RGB, Component, S-Video and composite. So, all the important signals are there without requiring proprietary adapters or internal modifications.

Audio

The new audio chip is an incremental update of the old SPU called… SPU2! Improvements include the inclusion of 2 MB of internal memory and 48 channels available (two times the original amount).

The SPU2 is made of two sound processors inside, referred to as CORE0 and CORE1, and runs at ~36.86 MHz. Each one processes 24 channels.

Curiously enough, these are still two independent processors and to configure them, you have to alter their registers. However, Sony warned developers that both sets of registers have to be set with 1/48000 seconds of gap. If you hurry too much, the behaviour of the SPU2 becomes unpredictable!

The SPU2 inherits the same effects available from the original SPU. The memory provided is used as a ‘work area’: You can store raw waveform data and allocate extra space to process it and apply effects on it.

Finally, the chip can mix all channels to provide stereo output. Now, here is the interesting part: The SPU2 can feed itself the mixed stereo sample as new input, this enables the EE to access it (to mix it with even more audio, for instance), or keep adding more effects (such as reverb, echo and delay).

Audio out

The audio signal is outputted through two media:

- Digital Audio: Referred to as the Sony/Philips Digital Interface or ‘S/PDIF’.

- Analog Audio: Goes through the digital-to-analogue converter and ends at the Multi A/V port.

I/O

Initially, the I/O of the PS2 wasn’t particularly complicated. Yet, subsequent revisions of this console completely disrupted both the internal and external designs. So, overall, this console exhibits many forms of I/O distributed across different revisions.

The special CPU

To start with, there’s a dedicated processor that arbitrates the communication between different components, this CPU is no other than the original MIPS R3000-based core found in the PlayStation 1. This time, it’s called I/O Processor (IOP) and runs at 37.5 MHz attached to a 32-bit bus [14].

The IOP communicates with the Emotion Engine using a specialised I/O interface called System Interface or ‘SIF’, both endpoints use their DMA units to transfer data between each other. The IOP also comes with dedicated memory - 2 MB of EDO RAM (just like the PS1) - used as a buffer.

All in all, this processor gives access to the front ports, DVD controller, SPU2, the BIOS ROM and the PC card slot.

The special upgrade

Be as it may, one year after the ‘Slim’ revision arrived in 2005, the MIPS core was swapped for a very unusual SoC that instead houses [15]:

- A PowerPC 440x5 CPU. This chip is part of the streamlined PowerPC 4xx series led by IBM and tailored for microcontroller applications.

- An Auxiliary Processing Unit (APU), a package composed of partial MIPS R3000A circuitry (the decoder and ALU), the good-old Geometry Transformation Engine and extra registers for inter-process communication.

- An Ethernet transceiver (previously sold as an external accessory).

There’s also 4 MB of SDRAM sitting next to the chip (2 MB more than before and ‘SDRAM’ this time).

The new package is referred to as PPC-IOP and runs at a lightning 440 MHz instead. Curiously enough, the PPC CPU will still be tasked with running MIPS code [16]. This is done with the help of a MIPS emulator called DECKARD (stored in the BIOS ROM [17]), which makes use of the additional SDRAM and the APU to accelerate this.

As the inner workings and operating speed of PPC-IOP are considerably different from the original IOP, there’s an additional database of patches with entries for each affected game [18]. Furthermore, DECKARD tries to approximate timings using an event handler. However, performance degrades during certain instructions [19]. Additionally, almost 24% of SDRAM is left unused for some reason [20].

Considering all this, I wonder why Sony redesigned the I/O ecosystem in a way that not only it degrades performance but it also wastes all its perks. Perhaps, it was only done to reduce manufacturing costs while keeping backwards compatibility (I explain more in the next paragraphs). It’s worth mentioning that, around that time, Sony had recently struck a deal with IBM to build the Cell processor as well.

Inherited compatibility

For those models bundling the predecessor’s CPU, one can suspect PS1 compatibility would be part of the package. Conveniently enough, Sony did bundle a PS1 emulator (called PS1DRV) that loads whenever a PS1 disc is inserted. When this happens, the IOP is under-clocked to run at PS1 speed, the EE is ‘repurposed’ to emulate the old GPU and the SPU2 is remapped to behave like the original SPU.

With PowerPC-based models, PS1DRV runs on top of DECKARD.

Available interfaces

This console kept the previous front ports that were included in the original PlayStation, it also features a couple of ‘experimental’ interfaces that appeared very promising at first.

The most popular additions are the two USB 1.1 ports. Its theoretical speed is 12 Mbps but that’s highly dependent on the IOP’s bandwidth (which tends to be considerably slower). Nevertheless, it was widely adopted by third-party accessories.

There were also some ‘experiments’ that didn’t last very long. For instance, the front i.Link port (also known as IEEE 1394 - or ‘FireWire’ in the Apple world). This port was used to connect two PS2s for local multiplayer, but it was removed after the third revision (presumably replaced by the ‘Network card’, more details below).

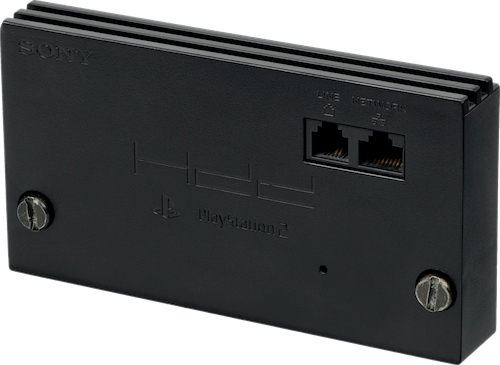

The unusual Ethernet + HDD combo

On the back of the console we also had a slot for PC cards. For this, you could buy the ‘Network Adaptor card’ from Sony that provides two extra interfaces:

- An Ethernet port, for online multiplayer.

- A proprietary and external Hard Disk Drive Unit port: This was sold by Sony and packaged a typical 3.5” ATA hard drive with 40 GB of space. It enabled games to store temporary data (or permanently install themselves there) for faster load times. Just a few games used this feature, though.

In later revisions, the PCMCIA port was replaced by an Expansion Bay where the 3.5” HDD could now be fitted inside the console. You had to buy first a Network adaptor which not only provided Modem and/or Ethernet ports (depending on the model) but also included the sockets to plug an ATA-66 hard disk.

Behind the scenes, the data in the HDD is structured using a file system called ‘PFS’ [23]. Strangely, the layout doesn’t contain a partition table, just a very primitive catalogue called ‘Aligned Partition Allocation’ (APA). This may be because Sony only shipped 40 GB drives. Hence, scalability wasn’t on their list of priorities.

The Ethernet transceiver within the adaptor supports transfer rates of up to 100 Mbps (12.5 MB/s). However, the observed rate is notoriously lower (down to 2 MB/s in some cases). The explanation for that is relatively simple: To achieve usable network communication, one is required to implement all the layers of the standard ‘OSI Model’; and the transceiver is just one piece of the puzzle. The rest is often delegated to the IOP (thus, done in software) but due to the IOP’s limited performance [26], this results in bottlenecks.

Slimming down

The Slim revision revised the whole Ethernet + HDD model: there’s no more Expansion Bay, but an Ethernet port is permanently installed on the back (particular models also included a Modem).

In addition to that, the new revision added a new infrared sensor, to be used with a Sony-branded remote controller (sold separately).

Interactive accessories

The new version of their controller, the DualShock 2, is a slightly improved version of DualShock.

During the days of the original PlayStation, multiple revisions of the original controller were released featuring different features (and also bringing fragmentation to the market). Now, for the benefit of developers, there was a single controller that unified all the previous properties.

Compared to the original DualShock, the new version features a slight redesign, it includes two analogue sticks and two vibration motors for richer input and feedback, respectively.

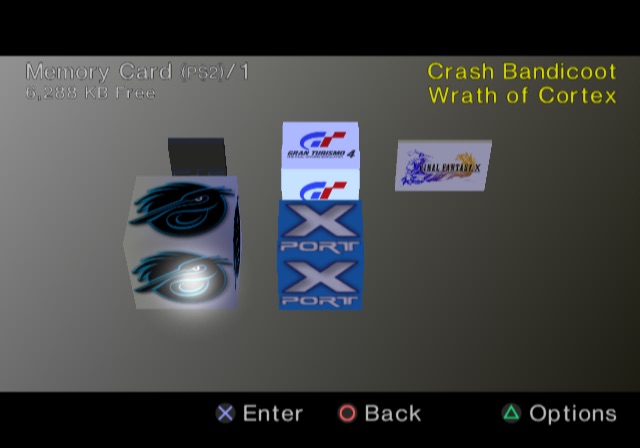

Next to the controller slot is the Memory Card one, now compatible with PS1 and PS2 cards. The latter cards embed extra circuitry for security purposes referred to as MagicGate, which enables games to restrict data transfers between different memory cards. The IOP takes care of encrypting and decrypting the content, and it does so with the help of the MagicGate chipset (found inside the Memory Card) and the DVD drive, the latter bundles the encryption keys.

Some third-party Memory Cards didn’t support MagicGate, however.

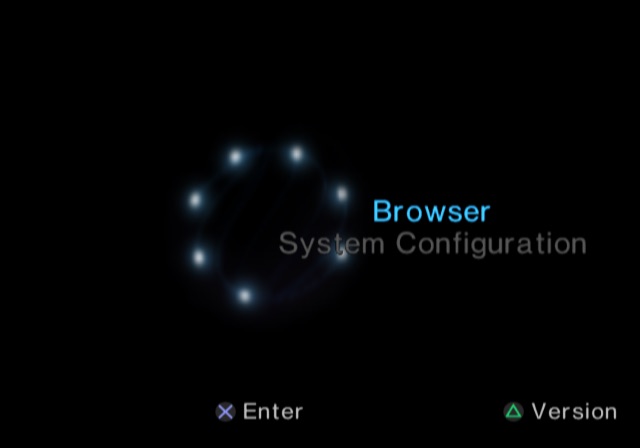

Operating System

There’s a 4 MB ROM chip fitted on the motherboard, this stores a great amount of code used to load a shell menu (that the users can interact with) but it also provides system calls to simplify I/O access [29] (which games rely on).

Upon receiving power, both the MIPS R5900 and the IOP will start at address 0xBFC00000 (that’s the signature reset vector for all MIPS CPUs). To handle the expected conflicts, however, the respective code stored in that address (pointing to the BIOS ROM) will make each CPU branch at a different location based on its identifier.

In the case of the R5900, the CPU will follow these steps [30]:

- Initialise the hardware.

- Load the Kernel from ROM into RAM. Once loaded, the Kernel will provide a layer of abstraction to applications (mostly games) to interact with the hardware. Additionally, it also exposes a multi-threading API (cooperative and priority-based).

- The Kernel loads

EELOAD, a kernel module which, in turn, bootstrapsOSDSYS. The latter is the program that displays the splash animation and the shell menu.

On the other side, the IOP will be initialising part of its hardware and then load multiple modules, these enable the IOP to access the hardware of this console. Once finished, the IOP will be put in a ‘waiting for command’ state.

It’s worth pointing out that the use of modules allows Sony to release new hardware revisions of the PS2 without changing the IOP (until they did), thereby lowering some production costs in the process.

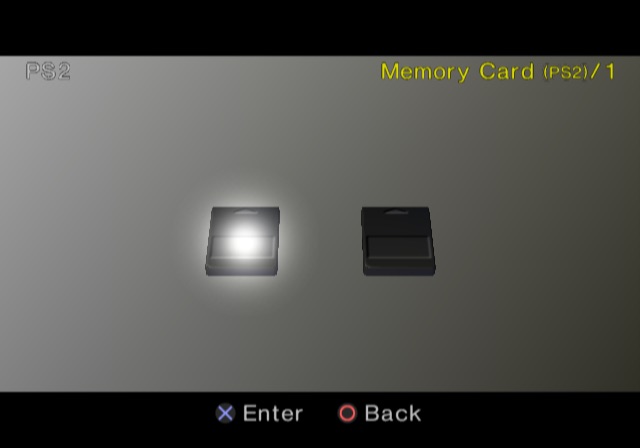

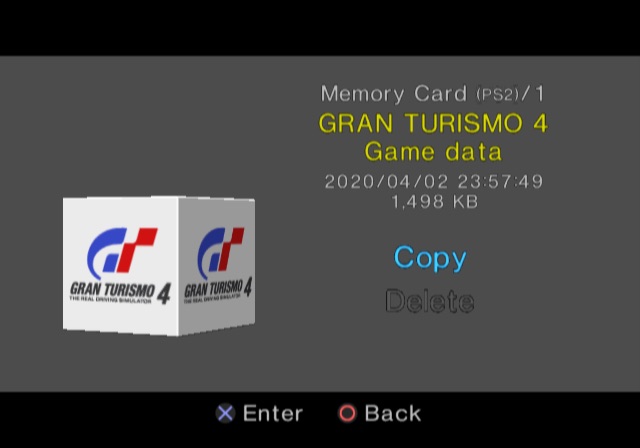

Interactive shell

The functionality of the PS2 shell is pretty much in pace with the other 6th-generation consoles.

The shell is composed of multiple user interfaces for managing typical operations, like manipulating the save data stored in the memory card or altering the clock. It also provides some advanced options, like changing the current video mode.

Updatability

The BIOS is indeed stored within read-only memory, but that didn’t stop Sony from amending it after leaving the factory. You see, behind the scenes, the BIOS left two doors open for future alterations:

- Applications (games and

OSDSYS) can monkey patch the kernel routines at runtime [31]. Both the official SDK and the unofficial ‘ps2sdk’ made extensive use of this, as Sony’s engineers subsequently discovered their Kernel to be riddled with bugs (pun intended). EELOADwill look for an updatedOSDSYSbinary stored in the Memory Card and/or the HDD [32]. Sony relied on this to add a DVD movie player and HDD support, as none of these drivers were bundled in the earlier revisions of this console.- These updates were distributed in installation discs that came with the console or the HDD kit (part of the Final Fantasy XI box set).

- Unlike the Kernel, which has to be backwards compatible with old SDKs, follow-up revisions of the console shipped previous updates in the BIOS ROM.

- To control distribution, binaries must be signed with Data Encryption Standard (DES) [33], a symmetric encryption system, using keys only known by Sony (in theory). Additionally, the binaries must be stored in a storage device with MagicGate support.

In any case, Sony eventually removed the second method in late PS2 models (with a BIOS version 2.30). I presume Sony wasn’t planning any more updates and this just added up to the attack surface.

Games

It is unprecedented the level of popularity this system achieved during the noughties, at the end of its lifespan (2013, after 13 years!) the game library was filled with 1850 titles [34].

What happened here is really impressive. The PS2 doesn’t have a ‘programmer-friendly’ architecture, (as seen from the perspective of a PC programmer) yet with such an amount of games developed, I too wonder if there were more factors involved (such as ‘licensing reliefs’, low distribution costs, cost of development, small form factor and what not).

Development ecosystem

Sony provided the hardware and software to assist game development.

On the software side, there was the PlayStation 2 SDK which included [35]:

- The Emotion Engine toolchain: A set of C and C++ compilers, assemblers, linkers and debuggers used to control each element of the EE. The main CPU was mainly programmed using C/C++, however, performance-critical components like the vector units were programmed using assembly (microcode/macrocode) instead.

- The pack also included an ‘Emotion Engine simulator’ which could roughly test out the code without sending it to the real hardware, although the simulator wasn’t as accurate as the physical EE chip.

- All of these tools worked on Linux, Solaris and Windows. The latter variant ran under the Cygnus environment.

- Low-level libraries: Interfaced many system functions (using BIOS calls).

- ‘Analysis’ tools to profile performance usage.

- Additional tools to connect with the official development hardware.

On the hardware side, Sony provided studios with dedicated hardware to run and debug games in-house. The initial devkits were bare boards stacked together to replicate the unreleased hardware of the PS2. Later kits (named Development Tool), had a more presentable appearance, enhanced I/O and combined workstation hardware (running RedHat 5.2) with PS2 hardware to build and deploy the game in the same case [36].

The combination of the Devkit, the official SDK and CodeWarrior (a famous IDE) was one of the most popular setups.

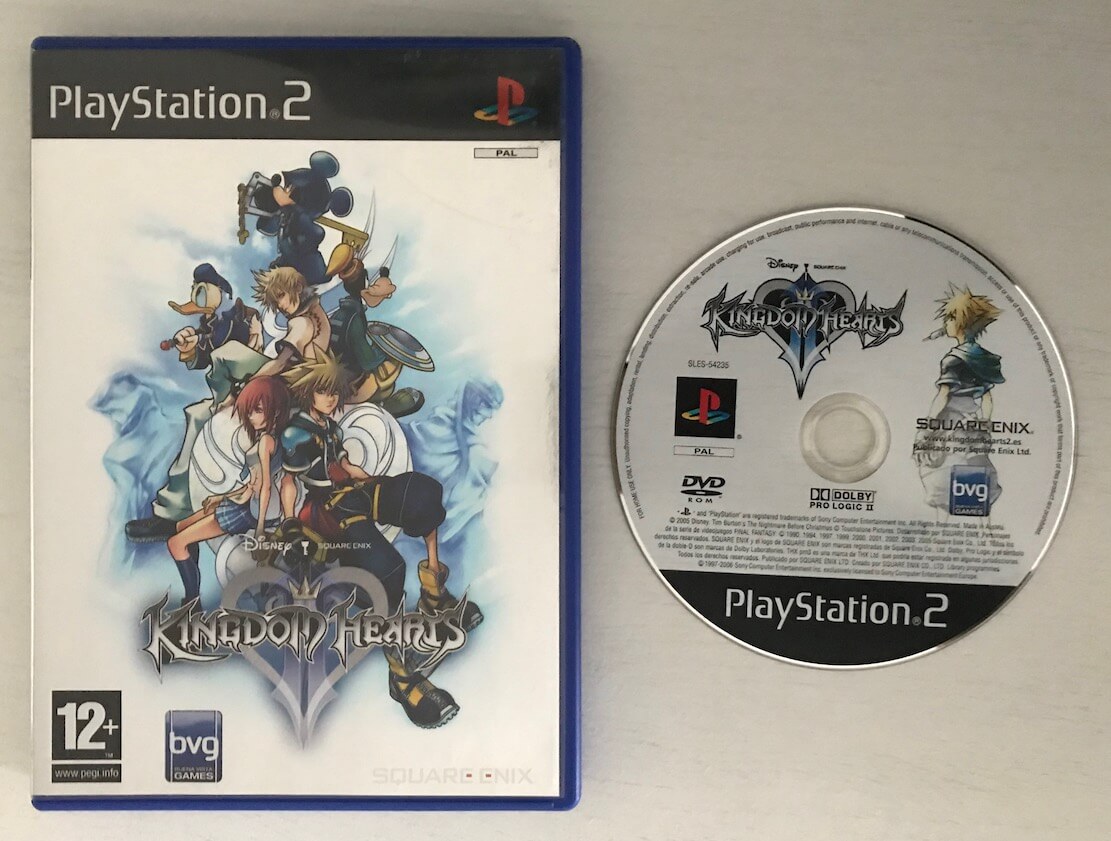

Medium

The disc drive can read both DVDs and CDs, so games could be distributed using either format, but for obvious reasons, you will find most titles in DVD format.

DVDs can hold up 4.7 GB of data in the case of DVD-5 (the most common ‘sub-format’) or 8.5 GB in the case of DVD-9 (dual-layer version, less common) [37]. There’s actually a third format, DVD-10, which is double-sided but no commercial games ever made use of it.

Due to the type of medium used, not only games could be played, but also movies. Now, this requires a decoder to be able to read the DVD movie format, and for that, the PS2 initially included the required bits installed in the memory card (after all, the card is just a storage medium) but later models came with the DVD software pre-installed in the BIOS ROM.

In terms of speed, CD-ROMs are read at 24x speed (so 3.6 MB/s) and DVD-ROMs are read at 4x speed (5.28 MB/s) [38].

Network service

As you have seen, the networking features of these consoles weren’t standardised until later revisions, which arrived four years later after the first release. Similarly, game studios were in charge of providing the necessary infrastructure if they decided to provide online services (like multiplayer). In later years, Sony deployed the Dynamic Network Authentication System or ‘DNAS’, it wasn’t an online server, but an authentication system to prevent pirated games from connecting online.

An unusual kind of game

Apart from all these games with their fancy graphics, Sony released a Linux distribution based on ‘Kondara’ (which is in turn based on Red Hat 6) available in two DVDs (the first disc is called ‘Runtime Environment’ and the second one is called ‘Software Packages’) along with a VGA adapter, USB Keyboard and Mouse; plus some developer manuals. The pack was known as Linux Kit and you could run the OS by booting the first DVD and then proceed like any old-school Linux environment. You obviously needed a Hard drive fitted in the console to install the Linux distro. Once installed, the first DVD was always required to boot this OS.

Linux Kit included compilers targeting the EE (gcc 2.95.2 with glibc 2.2.2) and assemblers targeting the vector units, along with a window system (XFree86 3.3.6) ‘accelerated’ in the Graphics Synthesizer [39]. Overall, this sounds like an interesting environment. In fact, one of the research papers I read to write this article was carried out using this setup.

Anti-Piracy and Homebrew

There’s quite a lot to talk about here, so let’s start with the DVD reader, shall we?

DVD copy protection

This area was particularly concerning for game studios, since this console used a very affordable disc format to distribute games. Thus, the risk of piracy was high.

When the OS loads a game, it does so by sending specific commands to the DVD reader. The commands specifically used to read the content of a game behave very differently from standard DVD commands (i.e. to read a DVD movie). It turns out authorised games contain an out-of-reach ‘map file’ in the inner section of the disc that indexes the filesystem by name, position and size. When the DVD is asked to read a game disc, it will always navigate through the disc using the map file, meaning that a pirated copy of a game, which could not include the map file, will be impossible to read.

This was complemented by a region lock system that prevented imported games from working in a console from a different region.

Circumventing protections

Having explained the most critical parts of this console, let’s take a look at multiple methods discovered (and commercialised) that defeated the protection mechanisms.

Attacking the DVD drive

As soon as the PS2 reached the stores, multiple third-party products appeared with the promise to ‘unlock’ the DVD drive. With no sign to support Homebrew (outside the Linux solution), piracy was the biggest beneficiary.

Modchips

As with any other console of its generation (and previous ones) using disc-based systems, it was a matter of time before third-party companies reversed-engineered the DVD subsystem. The goal here was to find a usable exploit that could force the driver to navigate through the file system without needing an out-of-reach map file.

This eventually materialised in the form of modchips, which lifted the copy protection checks and region-locking restrictions as well.

Cheats

Along with the modchips, which required soldering skills to install them, unauthorised but ‘genuine’ discs appeared in the market. These patched the Kernel to remove the region protection and use in-game cheats.

Most importantly, ‘cheat discs’ had the advantage of not requiring any modification on the console. I guess the best example to mention is CodeBreaker.

Disc swapping

In the middle of the latest advancements, yet another trick appeared. This time, exploiting the reader’s handling of faulty sectors. Swap Magic looked like another ‘genuine’ disc, but its ‘game’ tells the DVD to read a non-existent executable found on a deliberately faulty sector, halting the driver altogether [40]. This window of opportunity allowed users to swap the disc for a non-genuine one. Then Swap Magic, still loaded in memory, bootstrapped the main executable of the new disc, loading a real game at the end. All of this is carried out while the driver is still thinking a genuine disc is inserted.

This doesn’t necessarily require altering the console. However, depending on the model, the external case of the PS2 will have to be tampered with to block the eject sensors of the drive. In some models, placing pieces of cotton in certain places was part of the walkthrough.

Departing from modchips

As time passed, more research was gathered and shared about this console. Consequently, new and more sophisticated discoveries led to a new wave of development that didn’t rely on external hardware anymore, at least primarily. Furthermore, piracy wasn’t the main focus anymore. Instead, the ability to run third-party programs without the approval of Sony (called Homebrew) quickly topped the goals chart.

Independence overflow

The PS2 stores a database file called TITLE.DB in MemoryCard which contains information used to optimise the emulation of PS1 games [41]. When a PS1 game is inserted, the OS fetches the database file and loads the whole file in memory at a fixed address (strike one). The information parser is implemented using strncpy(), a function in C that copies strings (chains of characters) from one place to another.

For people familiar with C, you probably guessed where I’m going. The thing is that strncpy() doesn’t know how long is a string, so unless it’s terminated (by placing \0 at the end of the chain) the copy goes on ‘forever’ (with unpredictable results!). Luckily, this function contains an optional parameter that specifies the maximum number of bytes to be copied, protecting the copy from buffer overflows. As ludicrous as it may seem, Sony didn’t use this parameter, even though each database entry has a fixed size of 256 bytes (strike two).

Upon closer inspection in RAM, TITLE.DB happens to be copied next to a saved register, $ra, which states the address to return after the current function being executed finishes (strike three), leading up to The independence exploit [42]: Craft a TITLE.DB with a large string, embed an executable in it and design that string so $ra will be overridden to point to the executable. If you manage to upload that file to your Memory Card (through another exploit or a PC USB adapter) you got yourself a simple Homebrew launcher.

The discovery was published in 2003. Consequently, with the slim revision, Sony shipped a new BIOS ROM revision that patched this exploit. Curiously enough, it wasn’t the last blunder that exposed clumsy code.

The signature exploit

In November 2007, a hacking group started selling Memor32 [43], just another typical third-party Memory Card, except that for some reason it housed an FPGA and a USB port. It wasn’t until a firmware called Memento appeared on internet forums that the real nature of Memor32 became clear: To run unauthorised executables from the memory card, just like the Independence exploit.

The implementation of Memento relied on a flaw in the way the signature of the DVD player is checked. It was discovered that, while binaries have to be signed using Sony’s keys, the integrity of the binary is not checked. So, anyone could replace the executable code with something else (that still fits in the same space) and the operating system will happily run it. The Memento firmware used this exploit to disguise its payload within the DVD player, and bundles a couple of utilities that would allow users to load games (either from the disc drive or the HDD).

However, the popularity of Memor32 and Memento was soon displaced once a free (and initially open-source) alternative arrived: FreeMCBoot.

The universal solution

Once Memento got reverse-engineered, an alternative that didn’t require Memor32 appeared on the internet. FreeMCBoot exploited the same vulnerability except it could be installed on any MagicGate Memory Card. The only drawback is that another exploit (e.g. disc swapping) was still required to bootstrap the installer.

Interestingly enough, FreeMCBoot’s user interface borrows assets from OSDSYS, thereby providing a familiar menu to launch other Homebrew. It also patches the Kernel to add APIs to access mass storage devices in the USB 1.1 ports, something many homebrew apps relied on to locate additional files.

Additionally, the installer provides two options: to install only the files needed for the current console, or install a global setup for all PS2 variants. Curiously enough, the latter option was challenging to accomplish [44]. Initially, the installer would fiddle with the partition table of the Memory Card to avoid running out of space, something that wasn’t particularly safe.

As luck would have it, in 2011, the security system of the PlayStation 3 had just been compromised, exposing many secrets hidden within. Among others, a collection of MagicGate keys globaly used for PS2 backwards compatibility. From then on, it was no longer needed to resort to the limited DVD binary signature trick to craft PS2 executables. And so, since version 1.8b, FreeMCBoot has maintained its position as the safest and most popular method for running any type of Homebrew on a PlayStation 2.

Follow-up developments

Once the avenue for running Homebrew became more accessible, progress continued in the form of polishing previous exploits and developing Homebrew applications. Some of the latter ultimately facilitated piracy-related functionality, but they also expanded the limited capabilities of the operating system (i.e. by providing patches on games), I guess it ultimately depended on the intentions of its users.

To name a few notable examples of homebrew-related developments:

- FreeHDBoot: A variant of FreeMCBoot that instead installs on the HDD, where the system will also try to boot from.

- ps2sdk by the ps2dev group [45]: The defacto unofficial SDK for writing PS2 Homebrew without risk of copyright infringement. The project dates back to 2000, when it was only found in the form of loose libraries for accessing particular components [46] and over time unified into a single package for the benefit of Homebrew developers.

- LaunchELF by multiple authors [47]: A file manager with extra utilities. It was then continued as ‘uLaunchELF’ and, finally, ‘wLaunchELF’.

- Open USB Loader (OPL) by multiple authors [48]: Enables to boot disc images from multiple sources (HDD, USB, i.Link and even SMB and NMB over Ethernet) with patching capabilities.

- ESR by ffgriever [49]: Originally called ‘Vast CDVDV’, this is an application that tricks the whole system (including the DVD drive) into running a burned copy of a game without hardware modification. The original game content must be patched to disguise itself as a DVD movie (so the DVD drive doesn’t reject it), while ESR takes control of the Emotion Engine and IOP to redirect execution to the actual game.

Later years will also see new exploits uncovered:

- Fortuna by krat0s [50]: An alternative Homebrew launcher published in 2019 that relies on a completely different exploit. This time, it’s a buffer overflow in the icon parser of the saves manager (part of

OSDSYS) [51]. Its main advantage is compatibility with late PS2 models that removed support for externalOSDSYSupdates (thus, incompatible with FreeMCBoot). - OpenTuna by alexparrado [52]: An open-source alternative to Fortuna originated from reverse-engineering the latter.

- FreeDVDBoot by cturt [53]: A new vulnerability published in 2020. It consists of a new buffer overflow in the DVD player that can be exploited to perform arbitrary code execution. Users only need to burn a DVD with FreeDVDBoot to execute any binary they want, including the FreeMCBoot installer or even ESR (Sony was very lucky that this wasn’t discovered many years earlier! as others weren’t).

That’s all folks

Congratulations and thank you for reaching the end of the article! To be honest, there was so much to talk about that I wondered if readers would eventually get tired of PlayStation-related stuff after finishing this.

Anyway, in all seriousness, I do hope you discovered new things after reading this article and if you have any comments, don’t hesitate to contact me.

Until next time!

Rodrigo