Supporting imagery

Models

Released on 18/11/2012 in America, 30/11/2012 in Europe and 08/12/2012 in Japan.

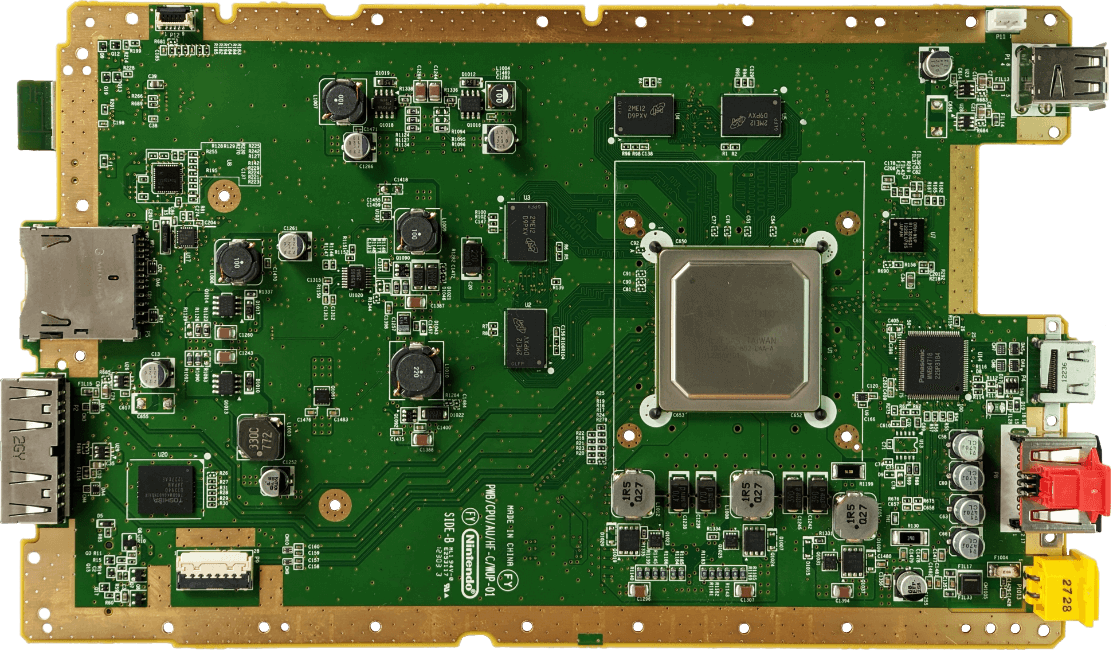

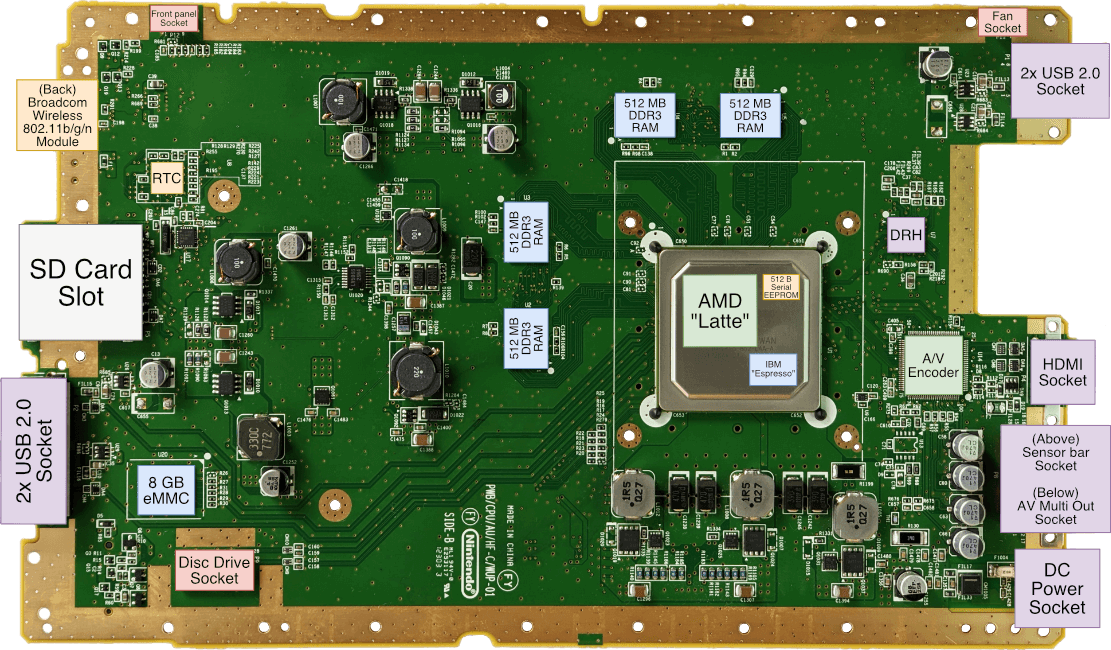

Motherboard

Interesting how there're lots of empty space, I presume the design had to be wide enough to accommodate the disc drive and the heatsink.

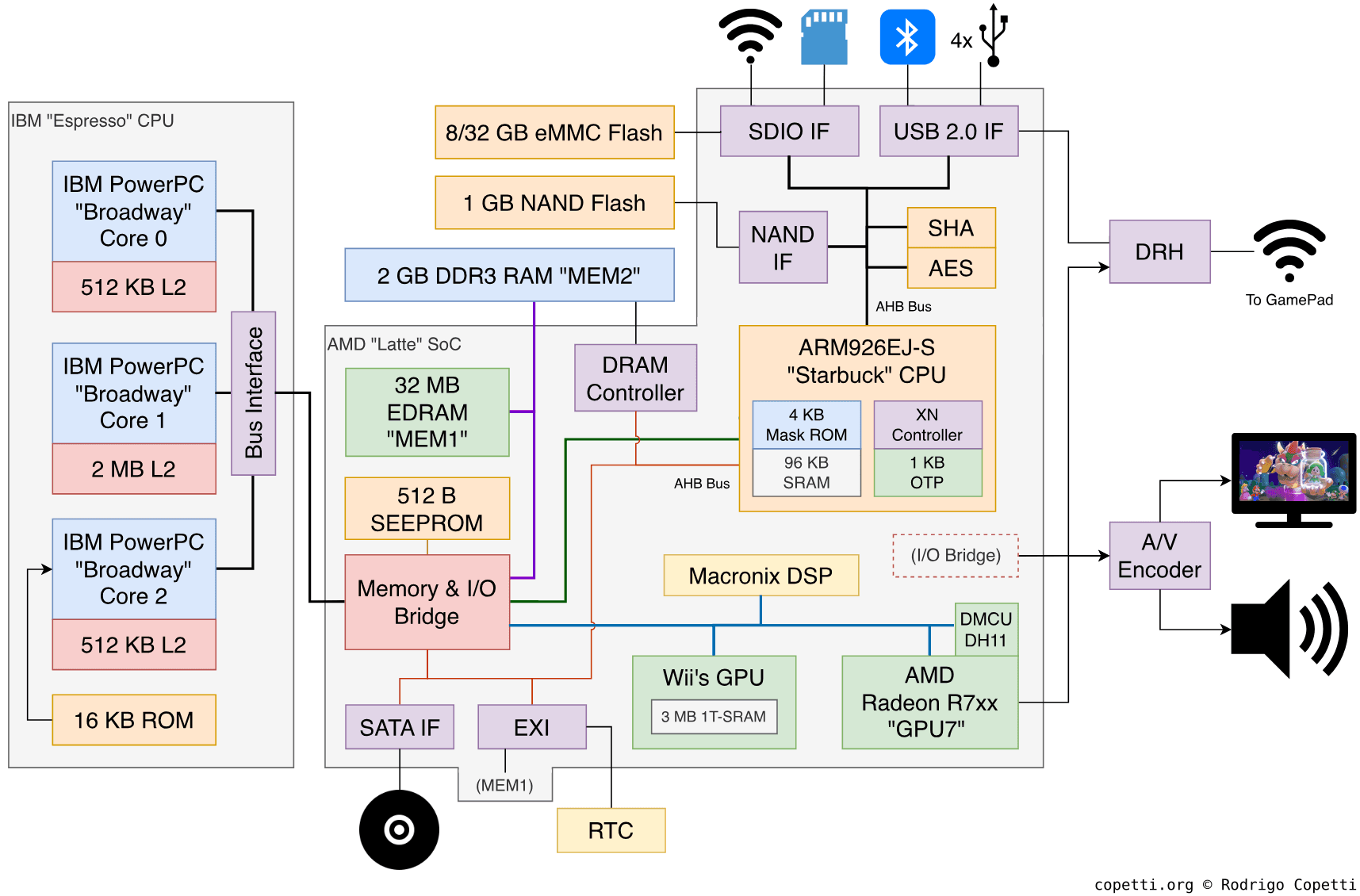

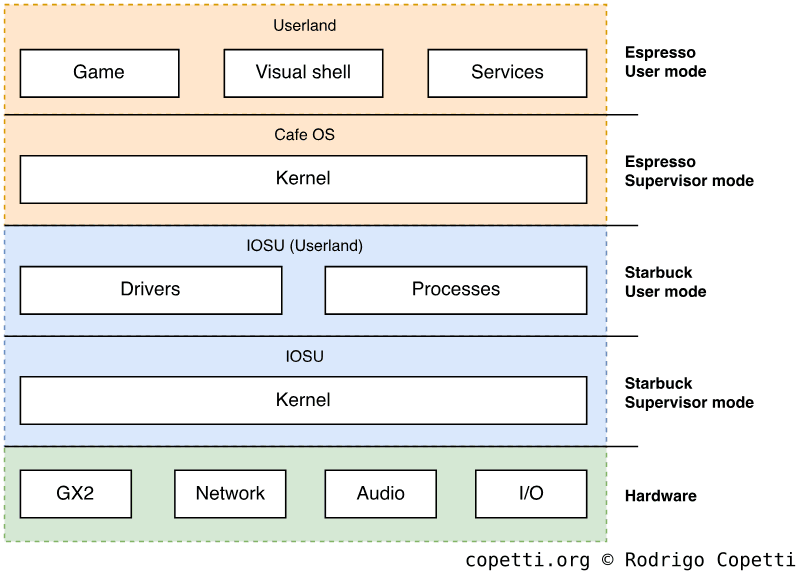

Diagram

A quick introduction

Already faced with the difficult challenge of replicating the triumph of the Wii, Nintendo’s new product also needed to save its loyal customers from the temptation of cheap smartphones and tablets. The result was a console that combines radical innovation with cost-effectiveness. In there, users found imaginative interaction methods while developers had to deal with the legacy technology underneath them.

The new issue of the Architecture of consoles has arrived. This time, we take a look at what would be Nintendo’s last joint project with IBM and AMD.

References to its predecessor and competitor

You’d be surprised that the Wii U shares its DNA with two somewhat distinct consoles: The Wii and the Xbox 360 (which, in turn, inherit technology from the GameCube and the PlayStation 3!). For that reason, I strongly recommend you read those write-ups first, as many of the technologies introduced here are related to their predecessors.

Furthermore, Wii backwards compatibility is a recurrent topic of this article. In contrast with the software emulation on the Xbox 360 and the provisional PS2 hardware on the PlayStation 3, the Wii U takes it to an obsessive level. It does come at a cost, though, which you’ll eventually see as well. In any case, the main goal of this article is to analyse the Wii U. So, Wii-related capabilities will be discussed separately from the main functions.

Next-gen controller

When it comes to Nintendo, the controller tends to be an engaging topic of discussion. Here is no exception, so I found it more captivating to start the analysis with this component before we dive into the main box.

The Wii U comes with a single wireless ‘controller’ (albeit nothing like seen before). It’s twice the size of a traditional controller but bundles twice the functionality. Its technical name is Display Remote Controller (DRC) but users better know it as GamePad. In there, we find a touchscreen, a set of buttons, a hidden stylus and many, many sensors. All in all, it’s one interesting brick.

Due to its abundance of hardware, you could consider it an independent computer by itself. However, due to its software, the GamePad ultimately behaves as a terminal linked to the console, with duties including:

- Input device by forwarding sensor data and button presses to the console.

- Output device by receiving audio and video streams from the console and reproducing them on the internal display and speakers.

- Signal processing by seamlessly encoding and decoding data streams travelling from or to the console.

In doing so, apart from being a controller, the GamePad was marketed with two functionalities in mind: A ‘second screen’ and a ‘mirror screen’. In the first case, the console may display exclusive information on the GamePad without consuming TV space. In the other, the user may use the console without requiring a TV anymore.

The GamePad’s display acts as a handy secondary screen to show the map and inventory.

Main gameplay happens on the GamePad, the TV just acts as a ‘projector’.

In practice, however, there wasn’t any standardisation in place. So, the adoption of either style completely depended on how the game was programmed.

Architecture

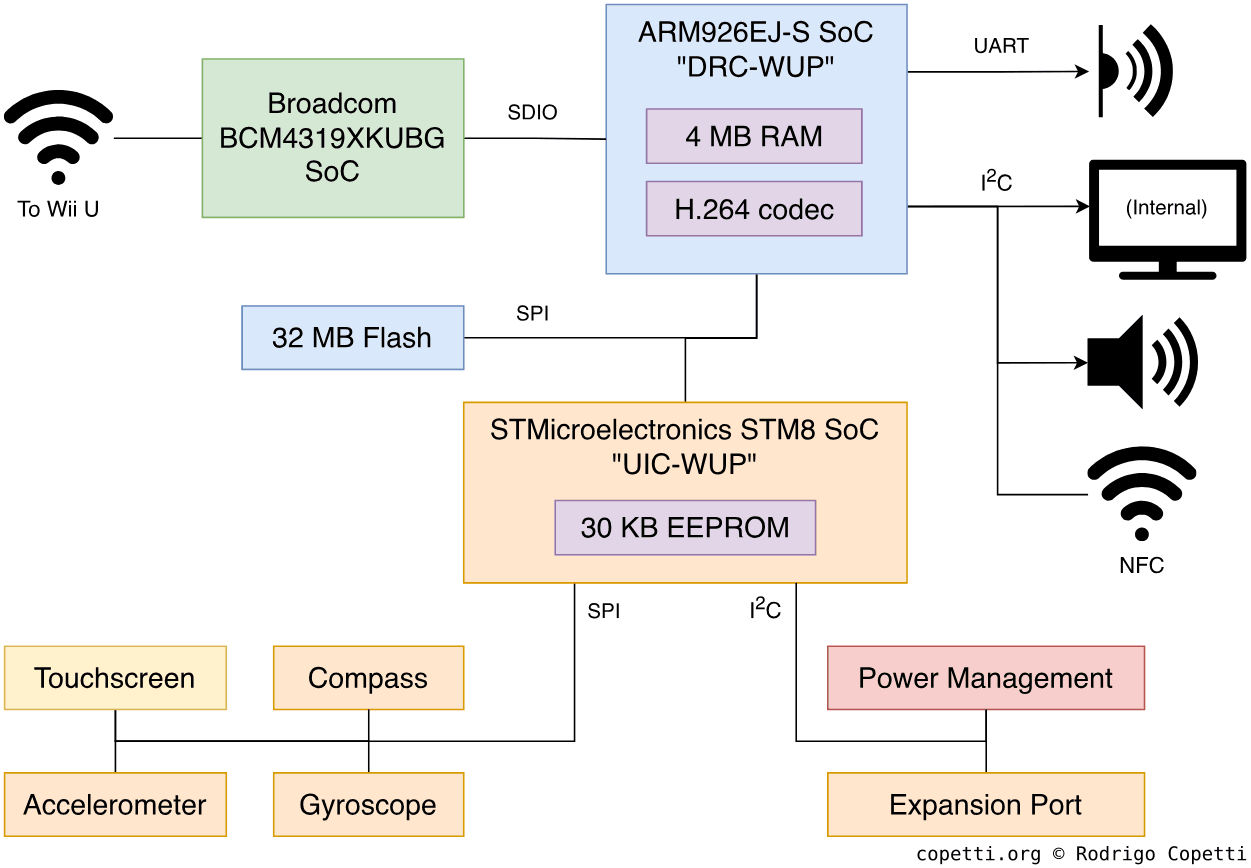

Let’s now see what the GamePad is made of, a tricky task by itself since the internals of the GamePad aren’t documented whatsoever. Luckily, a hacking group called ‘Memahaxx’ took matters into their own hands and completely reversed-engineered the device. If that wasn’t enough, they also took the time to share their discoveries with the public.

The device bundles three main chips [1] or, better yet, three independent computers:

Firstly, we’ve got DRC-WUP which is a System-on-Chip (SoC) hiding yet-another ARM926EJ-S (the same one from the Wii, how many of these do they have in stock?) along with 4 MB of RAM and a special H.264 accelerator for encoding and decoding H.264 streams. This is the main chip that controls the peripheral. It has access to the screen, audio and NFC functionality.

Next to the SoC, you’ll find the Broadcom BCM4319, another tiny computer that houses an ARM Cortex-M3 and the radio-frequency infrastructure that provides 802.11 a/b/g/n connectivity [2]. It’s worth emphasising that Broadcom’s choice of CPU is a bit more ‘contemporary’ than Nintendo’s, considering that the Cortex-M3 (with its second version of Thumb) was designed for embedded systems of the 2010s decade. To be fair, it’s known that Nintendo’s choices are not always based on ‘cutting-edginess’ but on cost and supply. In any case, the BCM4319 will be providing Wi-Fi connectivity using the 5 GHz band.

Finally, UIC-WUP is another Nintendo-branded component where we can find an STMicroelectronics STM8, 2 KB and 28 KB of EEPROM. The STM8 is one of those modern 8-bit microcontrollers used for small but repetitive tasks. That said, UIC-WUP is delegated with handling the remaining I/O.

The GamePad’s firmware (or firmwares) are stored in a separate Flash chip. This provides 32 MB worth of space accessed through an SPI bus. Curiously enough, the firmware code is not encrypted (facilitating the work of Memahaxx).

The rest of the GamePad’s motherboard is filled with I/O endpoints and unusual sensors. So, I will go over them in the ‘I/O’ part of this article.

Talking to the mothership

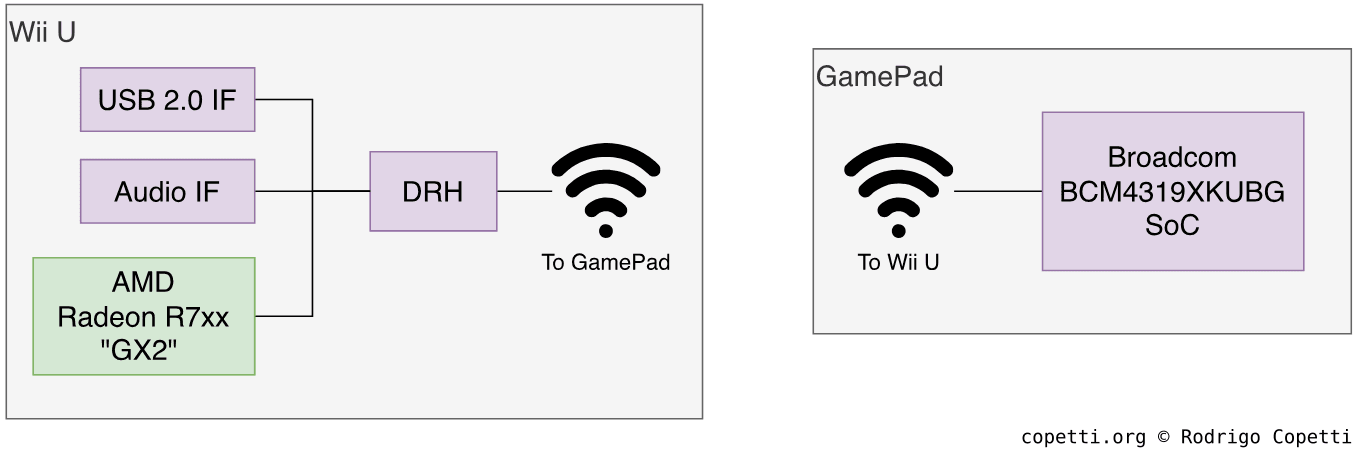

The Wii U’s motherboard includes a tiny chip called DRH which relies on the Wi-Fi protocol to communicate with the GamePad and the USB protocol to communicate with the rest of the motherboard. This includes the GPU, which streams frame-buffers directly to the DRH so they get displayed on the GamePad.

DRH runs a Real-time Operating System (RTOS) which implements the µITRON 4.0 specification. It’s quite sophisticated, offering cooperative multitasking and inter-task communication. Finally, it’s worth noting that the Wii U-GamePad communication over Wi-Fi is not mixed with the internet capabilities of the Wii U, that’s handled by a separate chip (and antenna).

Background functionality

Apart from the personalised implementation of the network stack (which will be explained in a bit), the GamePad does a lot of processing behind the scenes.

Once the GamePad is up and running, the device is capable of displaying an H.264 video stream by decoding it on-the-fly. The screen resolution is 854x480 pixels with a refresh rate of 60 Hz, which isn’t exactly HD, but it maintains 16:9 proportionality.

Strange use of standards

Similarly to how the Wii Remote mangles the Bluetooth protocol to avoid third-party usage, the GamePad breaks two Wi-Fi standards, namely WPS and WPA2-PSK, so they only work with the Wii U [3].

In summary, the Wii U and the GamePad communicate with each other using 802.11n in the 5 GHz band. The console acts as an access point (AP) and the GamePad acts as its single client. Be as it may, Memahaxx also reported that the console’s operating system implemented the possibility of using two GamePads at once, albeit left unused.

To establish a communication channel for the first time, both devices must be ‘paired’ first (in the same way a Windows laptop pairs with the Wi-Fi router by selecting the network name and supplying a password). This is done using the Wi-Fi Protected Setup (WPS) protocol, however, it’s not as easy as pressing the SYNC button and waiting until both devices pair. The process also involves the user selecting specific poker symbols shown on the GamePad as instructed on the TV (rendered by the console). Behind the scenes, the user is inputting part of the password, the GamePad then adds a hardcoded 5678 at the end of the password and sends it to the console. If the process has finished successfully, the GamePad receives the console’s SSID, BSSID and PSK values so it can automatically connect from now on.

From there on, subsequent connections rely on the WPA2-PSK protocol and both devices transfer their information using TCP/IP packets.

As a curious fact, the GamePad takes advantage of timestamps to keep Audio and Video streams synchronised. Timestamps are an attribute found on ‘Beacon Frames’, broadcast by access points for many reasons, one of which is to synchronise the internal clocks of in-range devices.

CPU

I hope you’ve got some time left as we still have to check out the internals of the Wii U, starting with the central chip.

Origins and hypotheses

Since the Wii U was announced (then known as Project Cafe), there’s been significant speculation about what would the new CPU be made of. At some point, journalists speculated that Nintendo would embrace a modern version of IBM’s POWER line [4]. I guess audiences were expecting a ground-breaking CPU as Cell and Xenon proved six years before. Moreover, with the decline of PowerPC (most apparently with Apple switching to Intel Core in 2006), the idea that any new CPU from IBM would come as a derivative of POWER wasn’t too far-fetched.

Well, there is one fault with the previous logic, which is that Nintendo doesn’t favour emerging technology. Their formula focuses instead on grabbing existing technology and finding innovative and clever uses. This is not necessarily a bad characteristic, as Nintendo engineers have been very clever in showing state-of-the-art applications with technology deemed ‘outdated’. Take a look at the Z80-hybrid of a Game Boy, or the under-clocked ARM9 on the Nintendo DS, or even the partially-updated GameCube called ‘Wii’. If there’s something common among all of these, is that all have broken sales records. Now, will the Wii U be part of that club? You’ll be the judge of that.

The 8th-generation architecture

In the past generation, Sony and Microsoft made strong bets (some riskier than others) on contemporary technologies at a reduced cost. With the Wii U, Nintendo looked at a slightly different direction, focusing on low-cost, low-power consumption and backwards compatibility [5]. The latter will have a strong impact on the final design of this console. Consequently, the new CPU doesn’t deliver any radical component and instead tries to catch up with the latest advancements in the industry (multi-core processing, GHz speeds, etc).

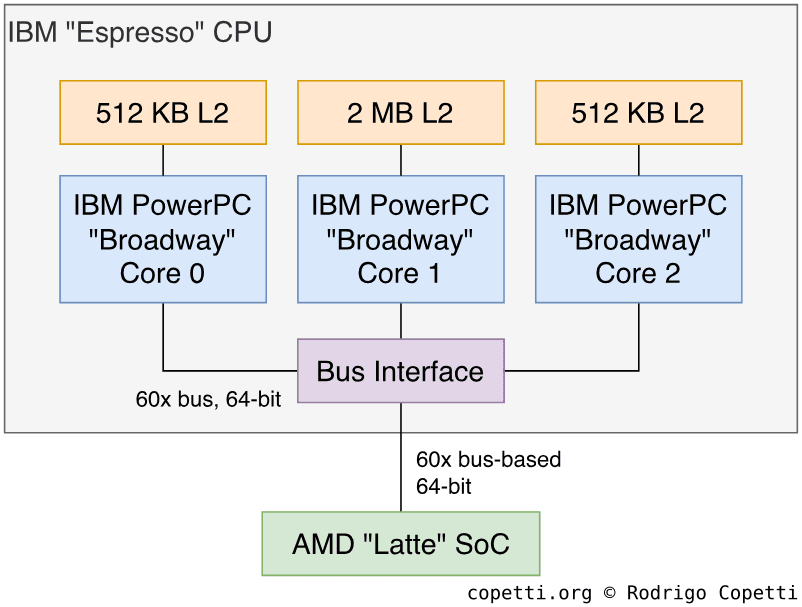

That being said, Nintendo partnered with IBM to deliver their new CPU. The result was Espresso and runs at 1.24 GHz [6].

Now, let’s bring Espresso forward:

… and as with any other article in this series, I’ll explain how it works.

Familiar faces

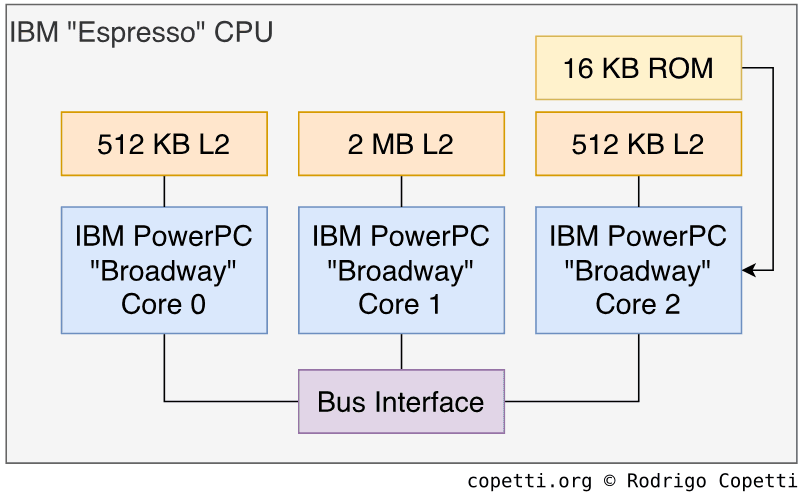

Before we start the real analysis, let me go back to the previous diagram. As you’ve seen there, Espresso is a symmetric multi-core system, just like Xenon. But that’s not all, as each of Espresso’s cores appears to be a replica of IBM’s Broadway, the exact same core used with the Wii (which in turn, is a tweaked version of Gekko, found in the GameCube).

Study of Espresso

We’ll now take a look at how Espresso is constructed. As I’ve already explained how Broadway and Gekko work, I’ll focus on the novelties of Espresso, namely its multi-core layout, cache system and memory.

At this point, it’s fair to say that neither Nintendo nor IBM have publicly documented the inner workings of Espresso (unlike Xenon and Cell from which many IBM engineers published papers on IBM’s now-defunct developerWorks portal). I guess that neither planned to commercialise Espresso outside the Wii U. As a consequence, this section has been possible due to the countless hours spent by hacking groups like fail0verflow (a.k.a Team Twiizers) which not only managed to reverse-engineer this system, but also take the time to publish documentation about it (don’t forget to look at the cited documents if you enjoy the topic). For this study, I’ve combined third-party research with public information from IBM (related to Broadway) and Freescale, and the result is what you see below.

‘Multi-coring’ Broadway

Espresso bundles three CPU cores based on the PowerPC 750CXe architecture. The design of these dates all the way back to 2001, meaning that the datapath and instruction set are roughly in the same state as they were 10 years before. For comparison, the PowerPC Processing Element (the main core of Xenon and Cell) grabbed the design of the POWER4 and re-engineered it for the requirements of the respective console.

Moving on, Espresso implements a symmetric multi-core layout… but how is this possible with those old cores? Well, in a (now defunct) FAQ portal, IBM has explained that the 750 already supports a multi-processing environment [7], it just needs extra work for maintaining cache integrity (between the different L1, L2 and the TLB). However, doing this through software cancels out the advantages of having a multi-processor design, so the idea was never taken forward… That is, until Nintendo reached IBM again.

In the end, IBM grabbed three Broadway CPUs, stepped up the clock to 1.24 GHz and wrapped them with extra L2 cache and the necessary circuitry to arbitrate bus contention and cache coherency (so it doesn’t have to be done with software). That’s Espresso.

A recallable bus

The external bus that connects the CPU cores with external components has an interesting history, dating back to 1993, with the launch of the Motorola 88110. After the formation of the AIM alliance, IBM and Motorola created a joint CPU based on their best inventions. IBM contributed with their POWER architecture and Motorola chipped in with the bus design of their 88110 CPU. In 1993, the PowerPC 601 was unveiled.

The PowerPC 601 featured a bus protocol called 60x bus. This was quite advanced and flexible for the time, already supporting 64-bit operations, fast clock speeds, cache coherency and multiprocessor configurations (hence the fact IBM stated the 750 could work with multi-CPUs right away) [8]. All of this reminds me of the anticipation of the Hitachi SH-2.

Back to the Wii U, IBM grabbed the 60x bus again to interconnect the three cores in Espresso. Additionally, they implemented a variant of the bus to connect Espresso (as a chip) with the rest of the motherboard.

If you wonder about the current adoption of the 60x bus, I’m afraid it’s been long superseded by an improved protocol called ‘MPX’ which Motorola implemented for their PowerPC 74xx line (also known as ‘G4’). The MPX bus solves deficiencies of the 60x like slow data throughputs with the use of ‘data streams’ to reduce wait states [9]. IBM, on the other side, presented their ‘Elastic Interface’ bus with their PowerPC 970 line (G5) and POWER4 [10].

More cache

With the Wii (and GameCube), Broadway/Gekko only disposed of 256 KB of L2 cache and 64 KB of L1 cache. With the Wii U, L1 cache stays the same with each core of Espresso, but two of them are now provided with 512 KB of L2 cache and the third’s got a whopping 2 MB of L2. In reality, this doesn’t mean there’s 2.5 MB of ‘practical’ cache, as different cores may need to cache the same portion from RAM, something that wouldn’t happen if cache were shared (but then, other problems would arise!).

All L2 caches found in Espresso are 4-way associative. Compare this to the 8-way associations in Xenon and Cell, which in the case of Xenon, was meant to alleviate the 3 cores competing for 1 MB of shared L2. With Espresso, iterating through cache associations will take less time, but there will be more frequent cache misses.

To handle cache coherency between the three independent L2 cache blocks, Espresso’s internal Bus Interface abides by the MERSI protocol (same as Cell/Xenon). For reference, Broadway (a single-core system) used the MEI protocol.

As a side note, L2 memory in Espresso is of type eDRAM, as opposed to SRAM. Furthermore, the L1 block still offers locked and RAM-to-L1 DMA instructions (as the GameCube’s CPU did).

Room for improvement

As emphasised by fail0verflow, the Wii U, as a system, is in fact not cache coherent. External I/O can alter memory without the awareness of Espresso, therefore cache is not automatically refreshed in those situations. By contrast, the Xbox 360’s Southbridge notifies the caches after peripherals DMA to main RAM.

Moreover, two existing PowerPC instructions made for multi-processing environments, lwarx (Load Word and Reserve Indexed) and stwcx (Store Word Conditional Indexed), no longer function as intended. As fail0verflow also noted [11], these now need a manual cache flush to work as intended. At least it’s not the first PowerPC variant to ship with broken instructions (see Xbox 360’s xdcbt).

It’s not all bad news, luckily. At least Espresso inherits Gekko’s ability for out-of-order instruction execution, something that had to be cut from Xenon and Cell.

Memory Available

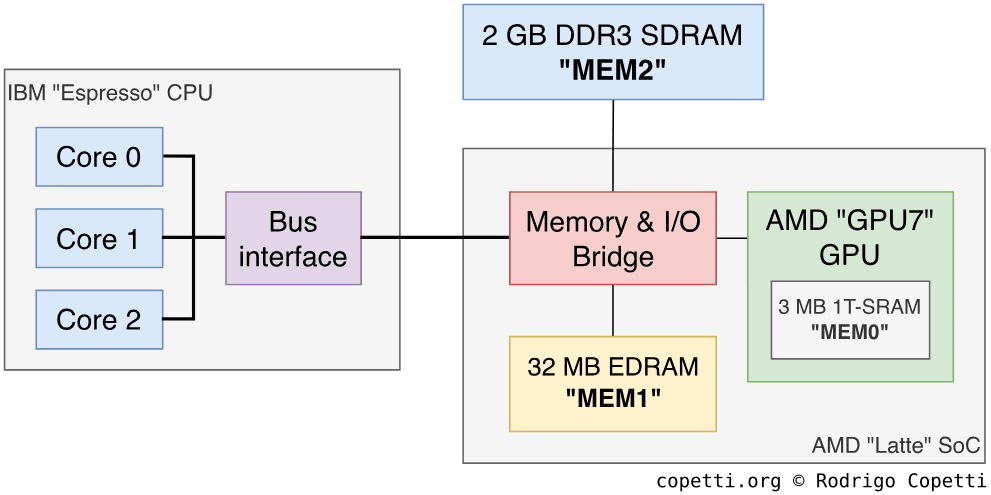

This section is simple and complicated at the same time. In summary, there are three places to store volatile data:

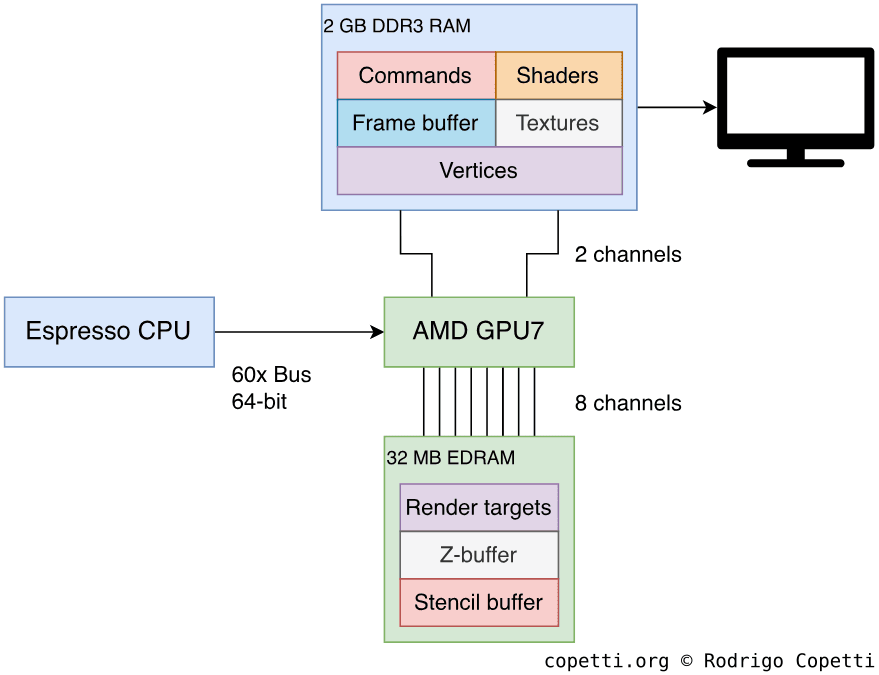

- A hefty chunk of 2 GB of DDR3 SDRAM called MEM2.

- A smaller block of 32 MB of EDRAM named MEM1.

- An even smaller piece of 3 MB of 1T-SRAM called MEM0.

The reason for such disparity is that you may remember MEM1 and MEM0 from the times of the Wii and GameCube. They’ve been carried forward with the Wii U, albeit with a slight increase of MEM1.

In any case, from the developer’s point of view, only MEM2 and MEM1 (the two bigger blocks) are accessible. The 2 GB of DDR3 may hold any kind of data (supplying both CPU and GPU), while the other two have more limited functions. MEM1 is used for graphics data (more details in the ‘Graphics’ section) and MEM0 is used by the operating system (more details in the ‘Operating System’ section).

In some ways, this system follows the Unified Memory architecture (UMA). Though, with MEM1 and MEM2 in the middle, I wouldn’t say this system is fully compliant with the UMA model (unlike some of its competitors).

GDDR3 or DDR3?

The old Wii employed GDDR3 memory, which is particularly fast for graphics operations. The Wii U’s choice is not only larger but also features a new type called DDR3 (without the ‘G’ at the start). Does this mean the Wii U has been downgraded? Confusingly enough, no.

GDDR3 memory is an improved version of DDR2 for graphics-related functions. Years later saw the arrival of DDR3, which succeeds both DDR2 and GDDR3. Have I lost you already? Well, to make matters more baffling, the follow-up GDDR4 and GDDR5 are enhancements over DDR3 and no other.

The nomenclature is unnecessarily deceptive. But let’s not lose our focus, the Wii U employs DDR3 and that means higher bandwidth compared to the Wii’s GDDR3.

Becoming a Wii

I’m eager to say that, while the new hardware may look underwhelming in some areas, the logic behind Wii backwards compatibility reaches the same level of dedication as the Nintendo DS or Game Boy Advance.

The methodology applied shares the same principles of those two consoles as well. Instead of resorting to software emulation or provisional hardware, the Wii U has been built as a superset of the Wii. Thus, it can easily replicate the hardware of the Wii by just hiding its modern features.

Having said that, whenever the Wii U decides to ‘become a Wii’, Espresso deactivates two of its cores (leaving a single Broadway core) and MEM2 hides 1984 MB of RAM (leaving the previous amount of 64 MB). Once in ‘Virtual Wii’ (vWii) mode, the old Wii game can safely assume it’s running on top of a real Wii.

There are more nooks and crannies behind this compatibility mode involving obscure I/O (explained in due time), so keep on reading if you are curious about this process!

The last venture of PowerPC

As we reach the end of the CPU section, it looks like this will be my last analysis of a PowerPC-based system (at least chronologically, I haven’t talked about the Apple Pippin yet).

The PowerPC has been an interesting development, with its ups and downs. And while it didn’t manage to dethrone x86, it did conquer three generations of consoles.

In any case, our beloved Espresso is, at its essence, a modern improvement to a fundamentally outdated platform. Both IBM and Motorola already dismissed the 750CL line in favour of the 7400 and the 970 lines, respectively. Yet, it’s curious to see how IBM had to dig up their old designs to produce a console that could compete in the 2010s. I guess the lack of a consumer version of Espresso is proof that IBM wasn’t interested in pushing Espresso any further.

But hey, just like with Xenon or Cell, it’s all part of an evolutionary line. I don’t believe these kinds of technologies are forgotten or abandoned, but their designs and expertise eventually merge into other projects.

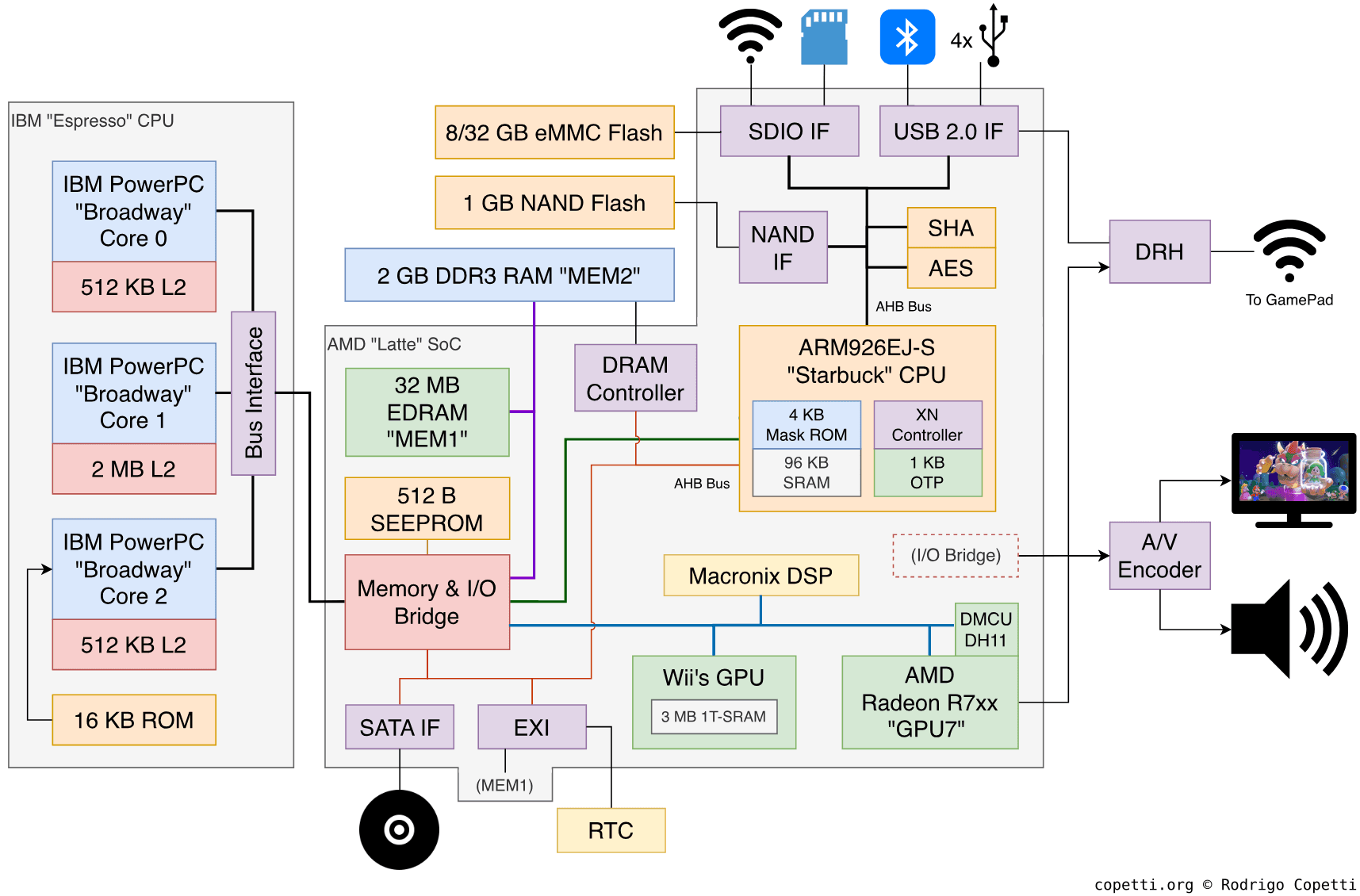

Graphics

So while the CPU can be considered a tribute to legacy technologies, let me tell you that the GPU is officially part of the next generation.

The graphics logic is found within a big silicon chip sitting next to Espresso, it’s called Latte, operates at 550 MHz [12] and, to make a long story short, it’s broad and complex. Latte houses a lot more infrastructure than just graphics, so don’t worry as the former will be explained in the next sections of the article. For now, just remember that the graphics block lives in Latte.

By the way, for the Italian readers, as you may know, the Wii U’s codenames are made of terminology related to coffee, and ‘Latte’ is no exception because that’s what non-Italians refer to ‘Latte macchiato’ :’)

Old partnerships with new challenges

Homologous to Nintendo’s good relationship with IBM, the company also maintained a unique partnership they started all the way back with the Nintendo 64.

ArtX was the group known for designing the Reality Coprocessor (then as part of Silicon Graphics) which then went on to invent Flipper, the GameCube’s unique SoC that houses its signature graphics processor. Years later, after being acquired by ‘ATI’, they supplied Hollywood for the Wii, from which we find a sped-up version of Flipper’s GPU. But most importantly and around the same time, ATI had been working on a cutting-edge invention for Microsoft. The result was Xenos and its new shader model for the masses.

Years after the release of the Xbox 360, ATI got acquired by a silicon company named ‘AMD’, which brings us to explain a bit of AMD history…

Titans in the ring

Initially known as the sidekick of Intel, AMD used to be the second supplier of Intel’s CPUs (i.e. 8086 and 80286), although this relationship broke down as soon as AMD started selling an unauthorised version of the 80386 that, to Intel’s dismay, improved upon the original designs of the chip [13]. This didn’t sit well with Intel and, soon enough, the two became head-to-head competitors.

Such was the competition, that in the late 90s, Intel’s plans to captivate the 64-bit market with their new line of ‘Itanium’ CPUs were soon thwarted by AMD’s simpler alternative: an extension of x86 called ‘amd64’ (also referred to as ‘x86-64’). Thus, Intel was forced to adopt AMD’s standard instead. For reference, amd64 still serves as the ISA of current x86 CPUs (as of 2022).

It’s never been all jolly for AMD, however. As the pressure from competing with Intel also brought a share of flops out of them (i.e. the abandoned “3DNow!” extension, the delay of Fusion, etc) and now, with the acquisition of ATI in 2006, AMD found itself facing two fronts: Intel in the CPU market and Nvidia on the graphics side.

The next Radeon

Now that we’ve positioned AMD on the map, let’s analyse the state of ATI’s Radeon line.

After the introduction of Xenos and its new architecture based on the ‘unified shaders’ model, ATI was still too busy with Microsoft’s project so they couldn’t allocate enough resources to bring Xenos to the PC market in the short term. Thus, the remaining teams focused on maintaining their classical x1000/R500 series, which left enough gap for Nvidia to ship their unified card named GeForce 8 (featuring the Tesla architecture) before ATI. Finally, in 2007 (two years after Xenos), ATI presented the Radeon 2000 series (codenamed R600) and its TeraScale architecture. The new design, now free of Microsoft’s budget and licensing control, brought all the advancements of Xenos along with optional extras for those users who were willing to pay the premium pricing.

Now, for the Wii U, ATI prepared a Terascale-based card for Nintendo, but it’s never been officially confirmed which model they based it on. Fail0verflow relates it to the Radeon HD 4000 series (codenamed R700) [14]. For reference, R700-based cards launched in 2008 and were an incremental update to the R670 and R600 series. The most apparent changes are the inclusion of faster video decoding hardware and support for OpenCL, though only the former will be usable (to some degree) on the Wii U.

In any case, the Wii U’s GPU goes by two names, Nintendo calls it GPU7 when referring to the hardware and GX2 when referring to the API. For this article, I’ll use the term ‘GPU7’ as I’ll be focusing on the physical capabilities.

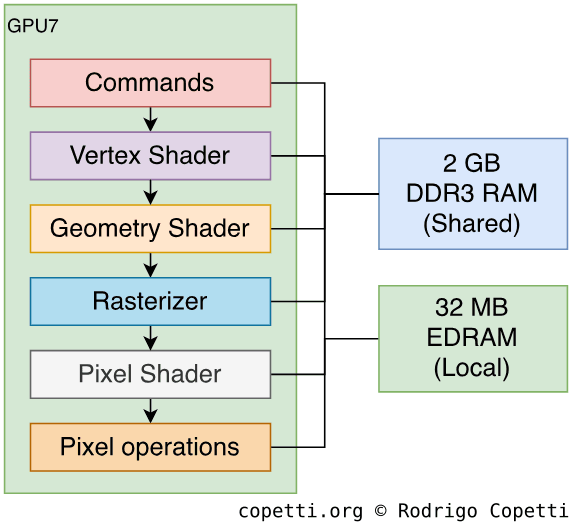

Architecture of GPU7

The TeraScale architecture is the materialisation of Xenos/Crayola ported to the PC market… and GPU7 is TeraScale brought back to a console. Its most identifiable trait is the use of a unified shader model that centralises both vertex and pixel units into a single block, now called SIMD unit.

It’s worth emphasising that when Xenos arrived, the API model was still based on the segregated shader model, so the libraries didn’t provide additional functionality that was now possible with a consolidated compute unit. Well, thanks to the subsequent updates (Direct3D 10 and OpenGL 3.3), that’s not the case anymore. Back to the Wii U, GX2 is the only API available and it’s based on OpenGL 3.3.

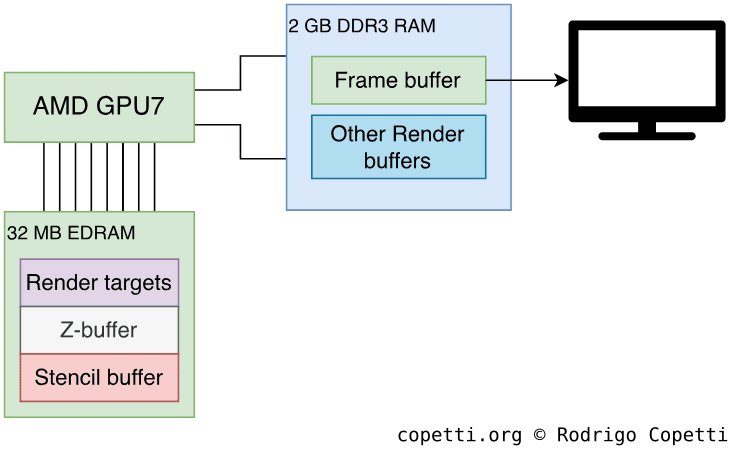

Organising the content

Most of the content related to graphics resides in the aforementioned 2 GB of DDR3 RAM called MEM2, which is shared between the CPU and GPU. That means the GPU must place its materials there, but MEM2 is relatively slow and not prepared for the contention that concurrent CPU and GPU work leads to. Therefore, Nintendo implemented something similar to the Xbox 360, and that is the inclusion of a dedicated and closer 32 MB of EDRAM (called MEM1) for fast operations (i.e. render targets and other high-demanded buffers). Consequently, not only large frames may be rendered, but also have extra space to perform post-processing (i.e. anti-aliasing) with acceptable performance.

Conversely, the Wii U’s EDRAM is larger than the Xbox 360’s (meaning the need for tiling is reduced). However, it does not include dedicated circuitry for post-processing.

Constructing the frame

This is the signature section of the Architecture of Consoles series where I attempt to explain the process of converting the geometry (coming from the CPU) into pixels (which users eventually see on the telly). Nevertheless, in this article, the explanations will be a bit different as the fundamentals of TeraScale were already explained in the Xbox 360 article.

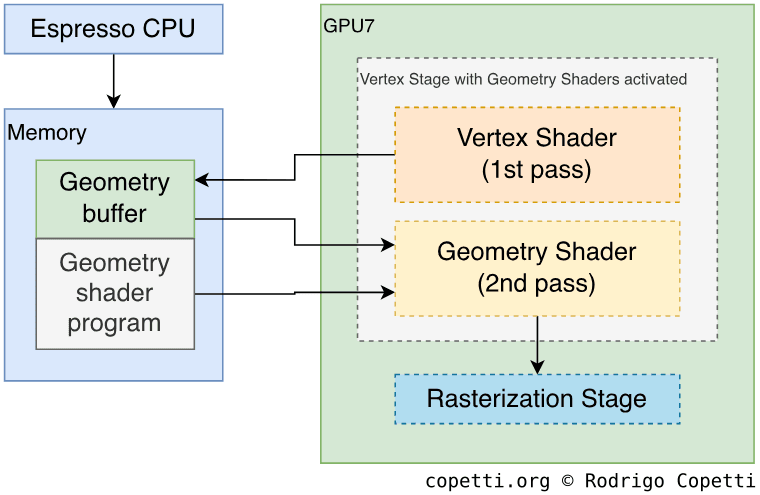

The most important changes since Xenos is the implementation (or better said, standardisation) of Geometry Shaders and Compute Shaders, both of which take advantage of the new capabilities of the unified shaders. This doesn’t mean GPU7 had to be completely redesigned to make way for these two stages, what happened is that APIs had been expanded to enable new applications without considerably changing the existing circuitry.

Being an AMD/ATI chip built for a Nintendo console, GX2 supports two shader APIs, OpenGL’s GLSL 3.3 and OpenGL ESSL. The SDK also comes with some extensions to provide functionality only available on GPU7, but it doesn’t support OpenCL and certainly not Direct3D.

Be as it may, GPU7 still inherits the designs of the Radeon R700 series, so GPU7’s pipeline is somewhat aligned to Direct3D 10.1 and OpenGL 3.3 standards. Although, their respective shader languages aren’t natively understood by GPU7 (they require proprietary compilers shipped with the official SDK).

As a side note, typical Radeon cards for the PC market use AGP or PCI-e bus interfaces. Well, the Wii U hardware still relies on the old-school practice of exposing I/O registers as memory locations [15]. I guess neither Nintendo nor AMD were concerned as this is all part of a custom design.

Let’s now go over the pipeline, stage by stage. Since the design is very similar to the Xbox 360’s Xenos GPU, I’ll try to focus on the novelties of GPU7 instead to avoid repeating information.

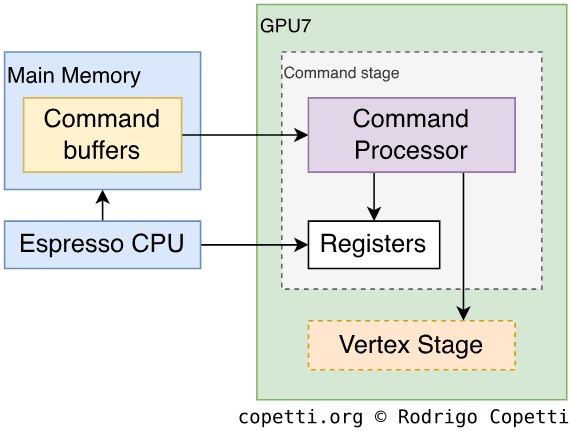

Commands

With most graphics cards, especially ATI/AMD ones, the starting point is always the Command Processor [16]. As we’ve seen many times before, this is the door between the GPU and the outside world (i.e. the CPU).

In the case of the GPU7, the Command Processor reads commands stored in RAM and activates the necessary engines within the chip. Most notably, GPU7 features a dedicated Direct Memory Access (DMA) controller to manipulate data between MEM1 and MEM2 without the intervention of the CPU.

Furthermore, DMA may work asynchronously (out of pace with the rest of the circuitry), so GPU7 provides a few commands to refresh its cache and synchronise with DMA (in the form of a semaphore) to maintain order.

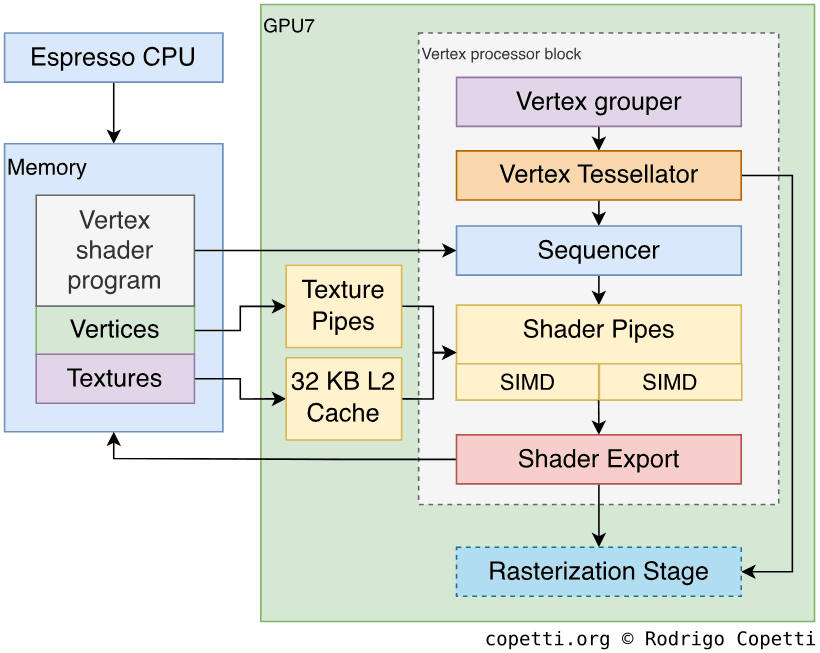

Vertex

At first glance, this stage is pretty much in line with Xenos/Crayola except that some blocks have been expanded (increased cache) while others have contracted (reduced number of ALU units and the Memory Export path is shorter). None of this necessarily means a performance decrease, however, as let’s not forget GPU7 is ~7 years ahead of Xenos.

To start with, let’s take a look at the ALUs. Xenos resorted to three shader pipes (blocks of 16 ALUs) to execute the vertex shaders. GPU7 only bundles two blocks of 16 ALUs, but each block is now wrapped around a larger circuitry named SIMD processor, which I assume denotes the addition of larger circuitry (dedicated 8 KB of L1 cache, plus the extra interfaces and control units) to sustain more concurrent traffic. Furthermore, each ALU is made of four ‘sub-ALUs’, allowing the former to compute vectors made of four scalars at once. ATI/AMD calls these sub-ALUs stream processors and it’s a common marketing term.

Now, instead of the Sequencer dispatching the calculations right away as they come, they are first combined into a larger batch of 64 vertices along with some meta-data to control the operation [17], this is called a Wavefront. The batch is then sent to the two SIMDs and, considering the fact there’re only 32 ALUs in GPU7, they take four cycles to be computed.

I assume this new design is what enables manufacturers to devise different ranges of graphics cards, with the most expensive including more SIMD units (thus taking fewer clock cycles to complete). As game consoles are not particularly famous for embedding high-end hardware (instead, they compensate by being more efficient), four clock cycles are what it takes in the Wii U to process a Wavefront.

Geometry

The geometry shader is a new stage of the graphics pipeline that appeared right after the two famous APIs (Direct3D and OpenGL) incorporated the unified shader into their specification. The purpose of this new stage is to allow developers to manipulate primitives (points, lines or triangles) as opposed to single vertices [18]. This can be useful for procedurally generating new geometry out of existing one (i.e. devise shadows, fur and so forth). The GPU7, like the Radeon R700, inherits compliance with OpenGL 3.3 and therefore supports this new shader type.

Behind the scenes, however, the geometry stage is just another ‘mode’ of the vertex stage. To make a long story short, if geometry shaders are activated, the vertex stage doesn’t forward the data for rasterisation right away. Instead, the outputted data is saved into a dedicated buffer in MEM2 and the vertex stage starts over but fetches data from the geometry buffer. Then, Wavefronts are assembled to grab the indices of up to 64 primitives along with meta-data denoting a geometry shader will be executed. Afterwards, the Sequencer reads the new Wavefront, parses the primitives and sends them to the two SIMDs for computing. The process is repeated until all primitives are processed.

Finally, the pipeline continues to the rasterisation stage.

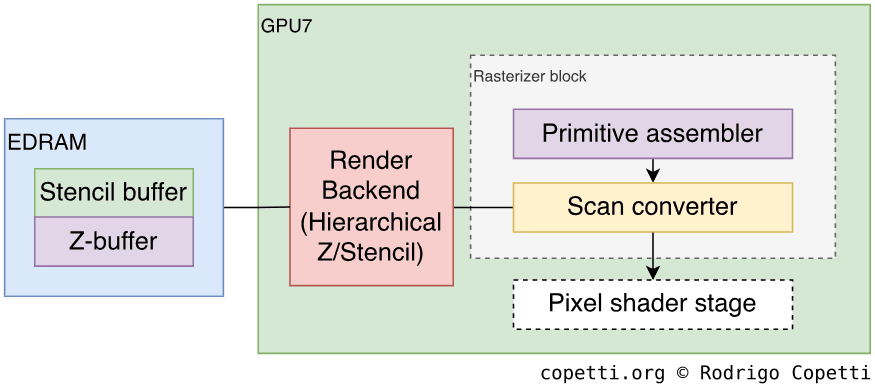

Rasteriser

The rasterisation stage tends to be much simpler than other stages. The main reason being the act of converting vertices into pixels is mostly systematic, and no extra programmability is needed (aside from a few parameters available to tweak). As such, this stage is identical to Crayola/Xenos.

Be as it may, the Z and stencil buffers are not allocated on dedicated memory anymore. Instead, the new Render backend block (performing Z and stencil testing, with support for hierarchical testing as well) must access RAM to work (either EDRAM or main RAM).

The rasteriser can compose frames of up to 8192 x 8192 pixels using 128-bit pixel formats [19]. This would allow massive frames with HDR colour quality. However and for obvious reasons, developers don’t need frames that big (1280 x 720 will suffice for this console), except HDR which will be used thoroughly.

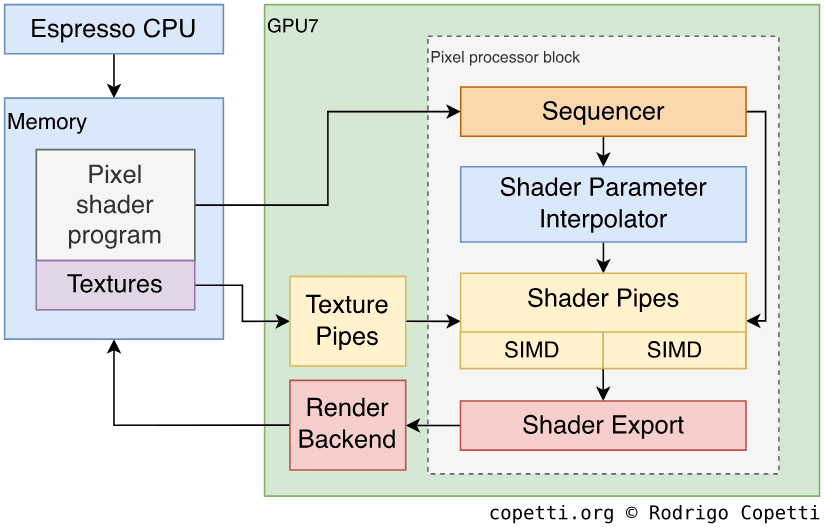

Fragment

The pixel shader stage follows the same methodology as the vertex shader except it’s now pixels being shuffled around. After going through Xenos’ pixel capabilities and GPU7’s new vertex pipeline, I’m afraid there’s not a lot left to explain here.

The block that fetches textures to the SIMD units is now called Texture Pipe and there’re two of them. Each contains 8 KB of L1 cache and they both share 32 KB of L2 cache when accessing RAM. Additionally, they can perform up to 16x Anisotropic filtering on the spot and can also fetch cube maps (used for environmental mapping/reflections).

I guess it’s worth pointing out that the shader model (OpenGL GLSL 3.3) adds an abundance of new routines (i.e. new types of texture blending, bitwise operators, texture swizzling) for manipulating textures and removes many constraints (such as the number of instructions allowed per shader). All of which makes the life of developers a bit easier.

Pixel Operations

Once the frame has been rendered, developers can apply more Z-testing (in case it wasn’t activated at an earlier stage), colour blending and, finally, export the pixels to the frame-buffer for display. This is all performed by the Render backends (there’s of two of them) which are found at the end of the Pixel shader stage.

Finally, even though the Wii U doesn’t feature the sophisticated circuitry that the Xbox 360 bundles within its EDRAM module, there are still many interesting capabilities provided by GPU7. This includes automatic Multisample Anti-aliasing of up to 16 passes (MSAA 16x) to soften edges, which surprisingly doesn’t require tiled rendering since the larger 32 MB of EDRAM (MEM1) of the Wii U is more than enough for these operations (well, maybe MSAA 16x will eat up too much MEM1, however, MSAA 8x is still acceptable).

Apart from that, we have to take into account the custom algorithms programmers may decide to implement. This is thanks to the flexibility of the APIs and the vast amount of shader operations available, including Compute Shaders (which offload CPU computations into the GPU).

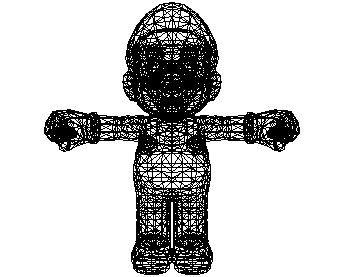

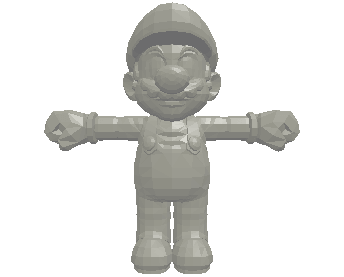

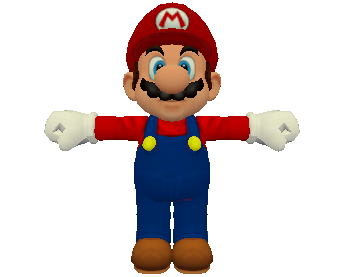

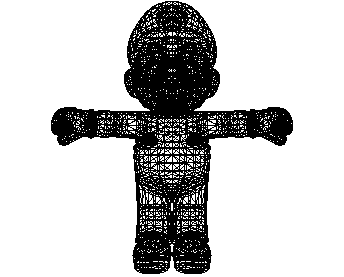

Interactive comparison

I’ve added new 3D models on the interactive viewer so you can check out the before (Hollywood’s GPU) and after (Latte’s GPU/GPU7) ‘effect’ by yourself:

Interactive model available in the modern edition

Interactive model available in the modern edition4,877 triangles.

Interactive model available in the modern edition

Interactive model available in the modern edition9,304 triangles.

While Mario’s textures don’t seem to offer a lot of extras on the Wii U, GPU7’s improvements lie in the extra surfaces and bones, especially on the hands and face, which make the model react more realistically to ambient effects and animations. In doing so, scenes look more natural throughout gameplay.

Video decoding

An additional feature beyond the 3D rendering capabilities of GPU7 is the inclusion of H.264 decoding circuitry that transforms streams of H.264-compressed data into raw frames that the GPU can understand (and subsequently render on the screen). The main advantage being bandwidth efficiency without performance penalties.

Consequently, the H.264 block is used for displaying motion video on the game in any way the developer prefers (i.e. within gameplay or as a cinematic).

Video Output

Time has come for Nintendo to ditch their proprietary analogue circuitry and embrace (at least one!) video standard. Lo and behold, an HDMI 1.4 socket is finally included on the back, along with the traditional AV Multi Out as a ‘backup’.

Now, even though the output resolution can go as high as 1080p, most games resort to 720p to balance game performance with the use of anti-aliasing and a large resolution. Using 720p also helps developers to keep support for 480i and 576i without altering the game logic (as the video encoder takes care of automatically downscaling the frame). This modus operandi matches the one of the PlayStation 3 and the Xbox 360.

A secondary GPU

With all being said, how come this console can still play Wii games? Is there some sort of GPU7-to-Hollywood emulator running behind the scenes? Well, the short answer is no. It may surprise you Nintendo went straight ahead and added the old GPU circuit from Hollywood (let’s call it ‘Wii GPU’) inside Latte as well [20]. This block only works when a Wii game is running. Although, the Wii GPU houses the old 3 MB of 1T-SRAM which is the one we now know as MEM0. So, at least the extra memory is used by the new hardware.

Furthermore, Nintendo also fitted an extra chip called DMCU to replicate the old Video Interface. According to fail0verflow, the DMCU is just a Motorola 68HC11 controller programmed to behave like the precursor. Its only purpose is to receive commands from Wii games and forward the frame to GPU7, so the latter can broadcast it to the TV. Due to the fact Wii games are made for PAL/NTSC screens, the GPU7’s video encoder must upscale it (which, in my experience, is not very good at doing so…).

If you wonder, there’s no ‘Wii GPU and GPU7’ co-processing available for Wii U games. It would’ve been ‘interesting’ though, albeit knowing one would bottleneck the other…

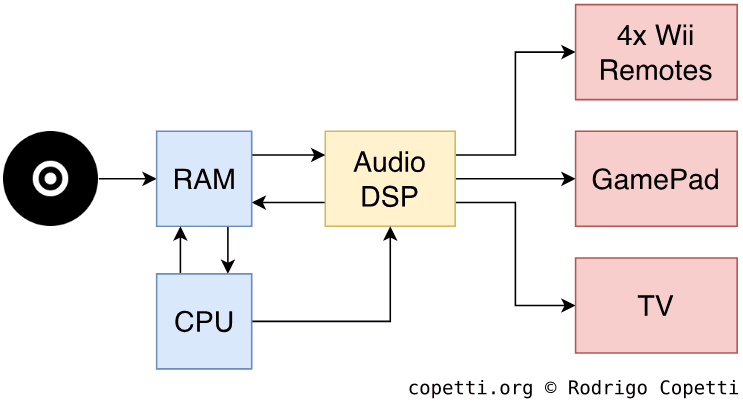

Audio

At first, I had assumed the Wii U implemented its audio functions through software (like its competitors started doing). But then, other questions arose: How is the complex DSP of the Wii emulated? Is Espresso powerful enough?

Well, that’s not all. Unlike the Wii, the audio pipeline of the Wii U must service three endpoints:

- The Television, expecting up to 6 channels (typically only 2/stereo).

- The GamePad with up to 4 channels (a.k.a surround audio).

- Up to four Wii Remotes (with one low-quality channel each).

Lo and behold, Latte also houses a custom DSP that performs audio synthesis. It’s operated through Nintendo’s libraries, although developers can extend the audio pipeline through software (at the cost of CPU cycles) if it’s not enough for them.

The DSP helps with mixing and sequencing tasks, the rest (i.e. filtering, effects, etc) is done with software (part of Espresso’s workload). Moreover, Nintendo’s libraries take care of workload management, where audio tasks are first assigned to the DSP and, in the event of full capacity, these are sent to Espresso.

The amount of workload and the resulting performance will depend on many factors, including the type of encoding streamed (i.e. ADPCM takes up more resources than PCM). Programmers must first test their code using the audio profiling tools provided to come up with an efficient implementation.

I/O

When it comes to I/O and interaction methods, Nintendo still manages to break the status quo. From the hardware perspective, the choices and internal organisation of these components tend to reach cost-effectiveness at obsessive levels. It may be because this area is under the complete direction of Nintendo’s engineers, and they strive for keeping the console at an affordable price.

A familiar ARM chip

Remember the old ARM926EJ-S that had complete control over the Wii’s hardware? Well, the same CPU is found in the Wii U. The main difference, however, is that Starlet is now surrounded by larger amounts of memory (96 KB of SRAM) and implements better algorithms for security-related tasks.

By the way, in the absence of an official name for the ARM9 CPU in the Wii U (after all, in the eyes of Nintendo, you shouldn’t know about this chip…), fail0verflow came up with their identifier: Starbuck.

That being said, Starbuck’s program has been greatly enhanced. I go over it in the ‘Operating System’ and ‘Anti-Piracy and Homebrew’ sections. For now, just remember Starbuck is the equivalent of the Southbridge.

External interfaces

Looking at this console from the outside, the Wii U offers the following interfaces:

- Four USB 2.0 ports to connect accessories or mass storage devices. Two of them are at the back and the others at the front.

- An SDHC card slot for storage.

- A proprietary Sensor bar port to plug the Sensor bar, enabling up to four Wii Remotes to control the Wii U (in addition to the GamePad). Remember the sensor bar is just four ‘dumb’ LEDs beaming infrared light, the real magic happens inside the Wii Remote!

Internal interfaces

As mentioned before, Starbuck is connected to the majority (if not all) of the I/O peripherals. Considering its strong backwards compatibility with the Wii and the inclusion of the same ARM9 core for I/O processing, I assume Starbuck still relies on AMBA buses to communicate with its peripherals, specifically the AHB type (since the new interfaces require higher amounts of bandwidth).

Having said that, Starbuck is connected to the following endpoints:

- The NAND Interface pointing to 1 GB of NAND storage. In practice, only half is used by the Wii U system and the other is reserved for backwards compatibility (the old Wii storage).

- Three SD Host Controllers, each providing access to:

- The separate Broadcom BCM43362 chip, for Wi-Fi connectivity (2.4 GHz 802.11 b/g/n).

- The SDHC card slot.

- Either 8 GB or 32 GB worth of eMMC storage for storing user data.

- Three USB 2.0 Host Controllers, each giving access to:

- The separate Bluetooth 4.0 module that wirelessly interacts with the Wii Remotes and the ‘Pro’ controller (all of them are optional).

- The aforementioned four USB ports.

- Another separate chip called DRH-WUP exchanges data with the GamePad using a 5 GHz Wi-Fi signal.

- An Advanced Host Controller Interface (AHCI), revision 1.2, to connect to the Disc Drive using the SATA protocol.

- A legacy External Interface (EXI) to access the Real-Time Clock (RTC). According to fail0overflow, the EXI block is also attached to some MEM1 for backwards compatibility reasons [21], allowing to emulate part of the legacy IPL ROM using portions of MEM1.

The supplemental interface

For another status-quo-breaking moment, let’s now go over some unusual features that the Wii U included, which at first no one knew what they would be used for.

When the Wii U reached the hand of users, they quickly noticed the GamePad had a Near-Field Communication (NFC) reader. Initially, Nintendo didn’t share the goals of such capabilities and some outlets even speculated that it would eventually enable NFC payments [23]. It wasn’t until 2014 that Nintendo finally unveiled their intentions with NFC technology: Figurines, which they called amiibos. These embed a unique NFC tag [24] and games that support them allow the user to ‘scan’ their amiibo (by placing them on top of the reader area of the GamePad). Then, the game will detect which type of figurine is placed and react accordingly (i.e. unlock premium content, create a special avatar and so forth). Tags may also bundle small storage (just 512 Bytes [25]) that games may use to store user data.

Overall, not only these figurines opened up another market for Nintendo but they also quickly turned into a rare collectible (for the enjoyment of scalpers). Though the market of these figurines wasn’t exactly ‘new’ as other companies like Activision and Disney were already commercialising this type of product.

Operating System

What if I tell you there are a total of four operating systems stored in this console? Two of them run in ‘Wii U’ mode, while the other two are only used for backwards compatibility.

As this topic can get very confusing, let’s start with the native Wii U-only systems.

With age comes wisdom

Just like in the original Wii, the Wii U runs two OSes concurrently, one in the CPU (Espresso) and another one in the I/O processor (Starbuck). However, both have been designed with thicker layers of abstraction and a more sophisticated security model. Hence, Wii U games do not run on bare metal anymore.

Starbuck’s improved OS

To start with, Starbuck’s operating system is now called IOSU (another name given by fail0verflow, meaning IOS + Wii U) and you will only find one variant of it. This means there’re no more update slots, although there’s an alternative IOSU referred to as ‘IOSU255’ which is only loaded when installing system updates.

IOSU is still composed of a multi-threaded microkernel, which is now able to allocate up to 180 threads (previously 100), along with drivers and modules to take care of I/O access and security.

One interesting aspect is that Starbuck disposes of two secured memory blocks for loading its kernel: Its internal 96 KB of SRAM and 3 MB of 1T-SRAM (known as ‘MEM0’) from the Wii GPU block. This is for performance and security reasons, as it prevents Starbuck from being exposed to tampering and reduces congestion.

Espresso’s new OS

First things first, Espresso now runs an actual operating system. That’s the most obvious change considering Wii games run on bare metal. This is called Cafe OS and it’s made of multiple components, not necessarily stored in the same medium [26]:

- A bootloader that bootstraps the system.

- A Kernel that provides a layer of abstraction between the hardware (in this case, through Starbuck) and applications. In doing so, it runs under the highest privileges of the CPU and provides many low-level functions (memory management, security, etc). Curiously enough, this component runs on the middle core (Core 1) as it provides more cache [27].

- User applications that run on top of the Kernel and provide functionality for the user. This includes the interactive shell, the game and other applications installed.

Moving on, the Kernel runs in supervisor mode and communicates with Starbuck using the same Inter-Process Communication (IPC) channel that the Wii relied on. This component can load multiple programs (processes) in memory, but it’s very limited in the number of processes it can run simultaneously (especially if they require foreground capabilities), I’ll talk more about it in a bit.

Cafe OS loads system and user applications using a proprietary binary structure called ‘RPL’, which is used for both executables and libraries. Moreover, the main executable is referred to as ‘RPX’. One of Cafe OS’ utilities, Loader, takes care of loading them up into memory (with the cooperation of IOSU) and executing them. Loader also performs dynamic linking to connect references of Cafe OS in the program with the physical Cafe OS installed in the console. Finally, applications are installed in the form of ‘channels’ which later show up in the ‘System Menu’ (the interactive shell).

Due to the way the Kernel organises the memory layout, the user is only able to run up to two types of programs at the same time. One is the ‘foreground’ program with the most amount of memory available (i.e. the game) and the other is a ‘background’ app with significantly less memory allocated (i.e. the web browser). The user may switch between the two without having to close either, but only one can be displayed at a time and, again, there can only be one ‘foreground’ and one ‘background’ app loaded. Otherwise, either gets closed/deallocated.

The big cost

It’s time to address something that may sound a bit outrageous: Cafe OS consumes 1 GB to run, that’s half of MEM2 that was supposed to be available for games. This means that the Wii U, having featured the immense amount of 2 GB of DDR3, only grants 1 GB to the most important application that users care about.

In my humble opinion, this is a real disappointment, especially considering an operating system like Mac OS X 10.4 “Tiger”, which also runs on similar PowerPC CPUs, provided a more sophisticated set of features and only asked for a minimum of 256 MB of RAM. Even so, game console manufacturers tend to design their operating systems so they consume the least amount of footprint possible, and it seems Nintendo couldn’t fulfill that requirement this time. On a curious note, it was even reported that Nintendo planned to ship new versions of SDKs and software updates that would reduce memory consumption from the OS side. Yet, here we are, with its successor already in stores and no further production of Wii Us in sight. Oh well!

Be as it may, there’s a slight compromise: ‘foreground’ apps may claim an extra 40 MB as long as they are being displayed (a.k.a shown in the foreground). However, as soon as the user switches to a background app, this block gets automatically deallocated. This is not exactly a ‘simple’ feature, leaving it up to developers to find good use.

Maintaining traditions

It all changes when a Wii game is played, as the Wii U enters a state called ‘Virtual Wii’ (vWii). There’s no emulator present, but re-shuffled hardware that makes Wii games think they are running on the original platform.

To enter vWii mode, Starbuck executes a program called cafe2wii that takes care of morphing the console into a Wii (a.k.a de-activating all the modern features) [28]. Now, there are different sets of binaries available to use (each with a variant of cafe2wii), specifically, OSv0 and OSv1. The choice depends on the type of vWii mode needed. In summary:

- Normal vWii launches the good-old System Menu, exactly what a real Wii does after pressing the power button. This is useful for playing a disc-based Wii game or for launching any channel installed.

- HAI vWii directly launches a Wii game (bypassing the System Menu). This is used for executing Wii games bought from the Virtual Console store. Hence, the Wii game may be installed in the Wii U’s dedicated storage (eMMC or external USB).

Luckily, not all the modern hardware in vWii mode is wasted, as the GamePad can turn into a mirrored screen with a controller as well. If that’s not enough, the front of the GamePad contains infrared lights that behave as a sensor bar, so Wii Remotes don’t require a TV at all.

Just like with any Nintendo console with backwards compatibility, once in Wii mode, the only way back is by rebooting the console.

Storage Medium

The Wii wasn’t shy in providing multimedia-centred storage options (the SD card was a nice addition). And so, the Wii U builds on top of that.

Having said that, let’s now see what storage options are spread throughout this console:

Boot ROMs

The 6th generation cemented the concept of an operating system in a video game console. Yet, the appliance was still exposed to the vulnerabilities resulting from combining off-the-shelf components with in-house ones. As console manufacturers couldn’t tailor the design of third-party chips, custom security components had to reside in separate locations within the motherboard, thereby being exposed to tampering and reverse engineering.

With the 7th generation, IBM presented a new range of PowerPC CPUs that embedded a hidden mask ROM within the silicon. This enabled the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 to house sensitive code in plain form (as CPUs only understand unencrypted code) without fear of being read by hackers. That being said, it’s now the turn for the Wii U so IBM also had something prepared for it: Inside Espresso, there is a hidden 16 KB of ROM connected to one of the cores. This is used as the first boot stage of Espresso and, once it’s been executed, it makes sure subsequent binaries are approved by Nintendo.

Combined this with Starbuck’s own 4 KB of Boot ROM (inherited from the previous Wii model), you’ve got two CPUs enforcing Nintendo’s security model as soon as they start up.

Sensitive ROMs

Nintendo also bundled other ROMs scattered around Latte containing very sensitive information.

The first one is 1 KB of One-Time-Programmable (OTP) memory where many encryption keys are stored. This memory was also found on the Wii but in a smaller size (128 Bytes). OTP stores the information used to encrypt/decrypt data and verify the integrity of existing data [29]. It also stores flags for enabling/disabling low-level functionality of the motherboard (i.e. JTAG). Additionally, OTP is segregated between Espresso’s bank and Starbuck’s one [30], as both will need to read different keys and subsequently lock OTP access at different points in time.

The second is 512 Bytes of SPI EEPROM (SEEPROM) which is writable (albeit not all of it is edited) and houses many configuration flags and miscellaneous meta-data [31]. Some data in SEEPROM is encrypted with keys found in OTP memory.

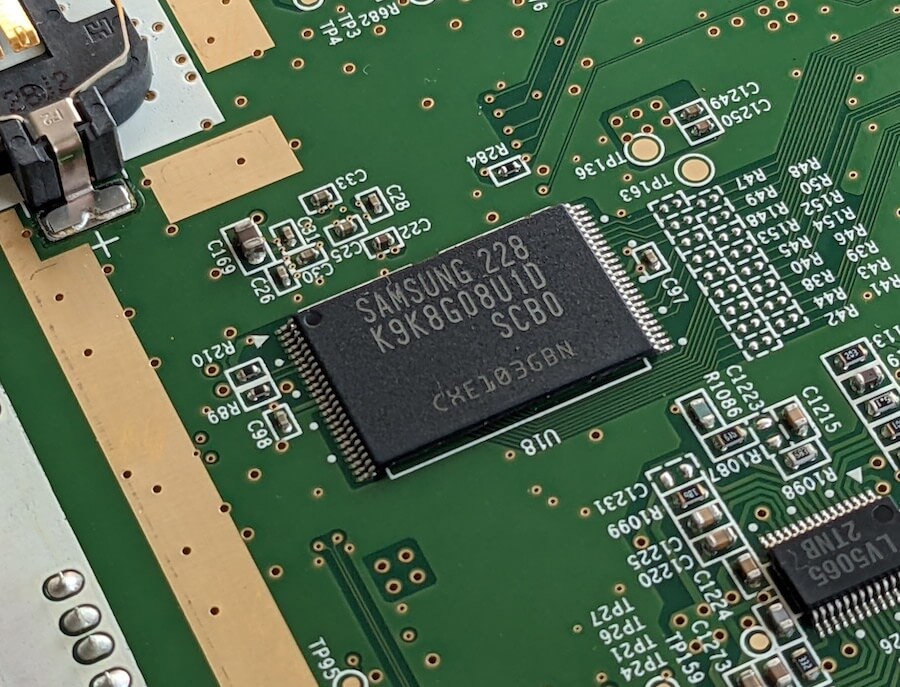

Diversified NAND

Having talked about the low-level part of the system, let’s take a look now at where the ‘visible’ part is stored. There are two storage spaces found on the motherboard:

Firstly, we’ve got 1 GB of NAND divided into two banks:

- The first 512 MB store the Wii U’s operating system (later-stage bootloaders and Cafe OS).

- The second 512 MB house the software that makes up the Wii’s operating system (System menu, IOS slots and channels) except the original bootloaders.

Secondly, either 8 GB or 32 GB of embedded MultiMediaCard (eMMC) depending on the model purchased, is available for user data only (downloaded titles, DLCs and game updates). Remember this may also include Wii titles downloaded from the Virtual Console store (which can only be launched from the Wii U’s System Menu).

Extra storage

For those users that run out of space pretty quickly, the Wii U came with support for external USB storage out-of-the-box. The only limitations, however, are that the medium will have to be formatted using the Wii U’s proprietary file system and only user data can be stored. As a side note, the Wii U’s USB ports only output up to 500mA of current [32], which ironically is not enough for typical USB HDDs (around 900mA). So, users had to resort to USB Y cables to combine the current of two USB ports.

Moving on, there’s also an SD card slot, but that’s only taken advantage of by certain programs and games that store exchangeable multimedia (such as images). Luckily, it supports FAT32 so no formatting will be needed.

Boot process

Having two independent CPUs can be difficult the setup. Still, Nintendo is no stranger to this practice. So, how does the Wii U manage to coordinate Espresso and Starbuck so the console ends up running an interactive shell on top of a secured environment? Let’s take a look.

Multicore chaos

Before we start I want to address the same problem that was present on other symmetric architectures like the Xbox 360: Symmetric cores must be coordinated so each one doesn’t take over the system at the same time. Well, Espresso adopts similar practices to x86, where only one core is activated upon switching on the CPU. Then, it’s up to the program loading in the master core to wake up the other two [33].

Nonetheless, all cores contain the same reset vector. Consequently, the program is responsible for asking itself which type it is running from and then proceed based on the answer. This modus operandi is similar to ARMv7.

Boot procedure

It’s time to see the boot routines and, let me tell you, they are not particularly simple. After all, it’s two independent processors with their unique security model being initialised in a serialised way, so that requires a lot of coordination. For simplicity’s sake, my summary is somewhat shortened to avoid feeding you up with lots of information, so don’t forget to check out the citations if you are curious for more.

On the other side, you don’t need to completely understand this to follow the rest of the article, so feel free to move on if it’s not your area of interest!

Alrighty, let’s begin already. Once the user presses the power button, the following happens [34]:

- Starbuck wakes up and proceeds to…

- Execute code found in its reset vector (

0xFFFF0000) [35], which points to its mask ROM (where the first boot stage,boot0, is). The first routine tells Starbuck to copyboot0into Starbuck’s SRAM, so it runs faster. boot0then initialises part of the I/O and nearby blocks by reading the flags found on OTP memory and SEEPROM. It then proceeds to fetch the next bootloader stage (boot1) from NAND.boot1is encrypted and signed, so Starbuck first checks its signature (RSA type), the integrity of the content (by comparing the SHA-1 hashes) and then proceeds to decrypt it (using AES). All of the keys and certificates needed are fetched from OTP memory.- More I/O is initialised. Then, SEEPROM and part of OTP is locked down from being accessed again. Finally,

boot1kicks off. boot1initialises even more I/O and prepares MEM2 and MEM0 for use [36]. It then transfersIOSU Firmwarefrom NAND to MEM1 and performs the same verification & decryption process. If everything went well, Starbuck disables the used OTP memory and zeroes out sensitive data. Finally, it jumps toIOSU Firmware.IOSU Firmwareis a collection of binaries. The first one launched isIOSU Loader, which moves the rest of the firmware (a.k.aIOSU) to specific memory locations (SRAM and MEM0). It then clears itself from MEM1 and jumps to SRAM, whereIOSU Kernelawaits.- The

IOSU Kernelfirst does a quick MEM1 check [37], but after that finishes, that’s Starbuck up and running with IOSU. To perform its functions, IOSU’s modules are found on MEM0. - Espresso is next, so IOSU copies

Cafe OS(in encrypted form) into MEM2 and kickstarts Espresso.

- Execute code found in its reset vector (

- The first core of Espresso powers on, then…

- The reset vector is at address

0x00000100, which at this point is masked by the Boot ROM, so it starts execution there. - MMU, L1/L2 caches and registers are cleared. Then, Espresso switches to ‘Translated mode’ (activates virtual memory).

- By fiddling with locked L1 cache and empty memory writes, the BootROM is copied to L1 (to run faster) without reaching external RAM.

- The reset vector becomes an infinite loop (to prevent intruders from attempting to reset the CPU).

- AES keys from OTP are copied into L1. Then, OTP is disabled.

Cafe OS Kernel’s header is copied to L1 and its signature is verified using the stored keys.Cafe OS Kernel’s data is hashed and decrypted by using the DMA engine to send blocks to L1 back and forth.- The now-unencrypted

Cafe OS Kernel, in RAM, is mapped and ready for execution. L1 and L2 are flushed; and the Boot ROM is disabled. Finally, execution jumps toCafe OS Kernel. - Espresso, now running

Cafe OS Kernel, checks configuration files that instruct it to launch theSystem Menuapplication. System Menuis fetched from NAND into MEM2 and processed like any other encrypted binary. If that goes well,System Menuis launched.

- The reset vector is at address

- The user is now in control!

vWii boot process

As soon as a Wii title is launched, the system proceeds with an ‘extra’ loader stage that turns the Wii U into a Wii. The process starts with Starbuck executing cafe2wii, which proceeds to [38]:

- Reboot Espresso.

- Slow down Espresso and disable the two extra cores.

- Upload a firmware for the DMCU video encoder.

- Upload the old fonts into an area of MEM1, which can them be accessed from the EXI interface (to replicate the old EXI route).

- Activate a compatibility mode on the AHCI interface (where the SATA disc drive is connected to) so it can be commanded using the old Disc Interface (DI) protocol.

- Copy the keys from OTP memory to its internal SRAM, as vWii will think the internal SRAM is the legacy SEEPROM.

- Disable Wii U-exclusive I/O, except the GamePad (unless it’s deactivated by the user or game metadata).

- Boot IOS. The choice of IOS slot depends on the vWii mode used and, if in HAI mode, the game.

- The IOS package for vWii has been slightly modified with additional modules. This includes

DI2SDto emulate the disc drive andOHCI1to translate the input from the GamePad into Bluetooth commands (thus, replicating the Wii Remote controller) [39].

- The IOS package for vWii has been slightly modified with additional modules. This includes

- Upload either the

Wii System MenuorNAND Boot Program(the binary that runs Wii titles) to MEM2, the choice depends on the vWii mode used.- As Espresso will have booted from its boot ROM first, it will only accept binaries using the Wii U’s security model. Therefore, both Wii binaries have been modified to comply with this.

- Kickstart Espresso and let it process and run the designated binary.

- The user is now in control (again!).

Interactive shell

The Wii U’s graphical user interface is called System Menu (or ‘Wii U Menu’) which, as you’ve seen before, it’s an application launched right after Cafe OS finishes loading.

Most of the services that the Wii U offers (i.e. disc game launcher, settings, online store, etc) are found in the form of foreground applications, the user can pick either from the System Menu. On the other side, a small set of functions (like an Internet Browser) are implemented as background applications and can only be launched from the ‘Home’ menu.

The System Menu interface has been designed with Touchscreen in mind. It also supports screen pointing interaction (as the Wii did) although its main controller is the GamePad.

On other news, Miis (Nintendo’s signature avatars) have also been ported to the Wii U. Not many games seem to care about them, but there are many system applications that use the Miis (mainly for decoration purposes).

For the first time in a Nintendo home console, the GUI is multi-user, thereby requiring users to set up a System account upon first launch (similarly to Sony and Microsoft’s interfaces).

After personally fiddling with the GUI, I was surprised at how slow navigation is. The experience is not sluggish, but switching between the apps (a necessary common recurrence) takes considerable time. This may be due to the security model in place (recall the bootstrapping process of Espresso and Starbuck binaries) being required to run every single time. Plus, it seems Espresso is not particularly fast for the algorithms implemented (an overview of the security model will be explained in the ‘Anti-piracy / Homebrew’ section).

The legacy shell

The System Menu comes with a particular app called Wii mode. This is the one that kickstarts the old System Menu to play Wii titles. Behind the scenes, this app bootstraps the aforementioned cafe2wii binary and we’ve already seen how this works.

Once in vWii mode, the Wii’s Home Menu is also capable of altering the console’s settings (i.e. the Wii Remote pairing information and settings). So, to avoid conflicting with the (native) Wii U configurations, IOSU’s kernel modules take care of synchronising both settings beforehand [40].

vWii mode doesn’t necessarily require a TV to use. If the user chooses to activate the GamePad, this will work as a display, sensor bar and ‘classic controller’ (an optional accessory during the Wii days). The last function, however, is only available for Wii games purchased from the eShop (part of the Virtual Console catalogue).

Nintendo also took care of bundling new Wii U-related channels in vWii to make the user’s experience a bit more enjoyable.

Finally, the settings button on the System Menu will only allow to manage save data (the ‘Wii System Settings’ screen has been removed for practical reasons).

Updatability

Both operating systems are very much ‘updatable’ with Nintendo issuing software updates online and through game discs. In doing so, new accessories can be supported, apart from improving the software and/or patching system vulnerabilities.

When the updater is launched, Starbuck loads a different variant of IOSU called ‘IOSU255’ and proceeds to install updates from there [41]. The update package can include both updates for Wii U and vWii mode.

Games

In here we scratch the surface of Wii U game development, distribution and subsequent online services provided by Nintendo.

Development ecosystem

Game studios were offered two sets of products to develop Wii U games, one was a selection hardware units and the other was a bespoke software package.

Hardware Kits

Similarly to the Wii, Nintendo distributed multiple development units, to name a few [42]:

- The Cafe Tool for Development (CAT-DEV) is the flagship devkit for development, debugging and profiling. It houses larger amounts of memory and enhanced I/O to assist with prototyping. The CAT-DEV communicates to a PC over TCP/IP.

- Once development reaches its testing stage, Cafe Tool Reader (CAT-R) is available to testers to try out beta builds without requiring to purchase the more expensive CAT-DEV. CAT-R is shaped like a retail Wii U and the only changes are found in its software. Its disc drive can only read CAT-R Discs which are identical to retail discs but engrave alternative signatures made for development units. An equivalent GamePad accessory was also shipped and purchased separately.

Software Kits

The official Software Development Kit (SDK) was called Cafe SDK and came bundled with:

- The set of libraries that interact with Cafe OS and therefore, the console itself.

- Green Hill’s MULTI compilers and Integrated Development Environment (IDE), now that CodeWarrior reached obsolescence.

- It’s worth noting the competition relied on Visual Studio as their IDE of choice.

- Various utilities to connect to CAT-DEV equipment.

- A GLSL shader compiler and an HLSL→GLSL shader transpiler. This is the reason GPU7 is said to be compatible with GLSL (OpenGL’s shaders) or even HLSL (Direct3D’s shaders). However, programmers can’t use GLSL and/or HLSL shaders on GPU7 without compiling them into native GPU7 code first.

- Proprietary linkers to package up Wii U executables/libraries (in the form of

RPXandRPLfiles).

These tools expect a host running the 64-bit version of Windows 7 along with Cygwin installed.

Finally, it’s worth reminding that, since games now run on top of Cafe OS, libraries are not linked statically anymore (a.k.a bundled into the binary). All Cafe OS references are linked dynamically and the OS now takes care of runtime linking.

Medium

This section is very much aligned with the 7th generation of consoles. In summary, there were two types of game distribution: Retail and Online.

Retail stores sold Wii U optical disc, a proprietary disc medium designed by Panasonic in an attempt to replicate many capabilities of the Blu-ray disc… without using Blu-ray discs. These can hold ~24 GB of data but only ~20 GB is available for actual game data, the rest is used for storing software update files, meta-data and other information Cafe OS needs to read.

The same drive is also able to read Wii optical discs which, in turn, are similar to the standard DVD format. However, the drive doesn’t support either DVD or Blu-ray’s playback capabilities.

Apart from discs, users had the option to buy Wii U games and expansions (a.k.a DLCs) using the eShop channel. The catalogue also included Virtual Console games.

On the surprising side, the Virtual console inventory has been expanded with Wii, Nintendo DS and Game Boy Advance titles. In the case of DS and GBA ones, the structure of a VC game is the same as their predecessors’ (Wii’s VC games), where both the emulator and game are packaged up as a game title. In other words, there’s no shared emulator, unlike the PlayStation 3.

Finally, eShop purchases are installed into the eMMC storage or external USB devices, whichever the user prefers.

Game updates

Games are updatable using ‘Update files’. These are offered to download, if available, by the System Menu right before the game is launched.

Behind the scenes, update files are installed on user storage like eShop games or DLC. Cafe OS supports two types of updates: Replacement files and delta patches.

Network service

It’s been good fun with WiiConnect24, but Nintendo has since replaced it with a new set of services grouped under the Nintendo Network brand.

The first apparent difference is that, in order to access online services (including eShop and multi-playing), users must first register a Nintendo Network Account. This account is then paired with the previously created System account.

From the developer’s perspective, the official SDK bundles libraries that interact with Nintendo’s authentication servers. Developers then use the authentication data to interact with their own servers and provide whatever online functionality they offer.

As a side note, Nintendo also ventured into social media services by bundling new types of applications like Miiverse. Analogous to Facebook walls, Miiverse enabled users to post notes and make comments about their favourite games. To liven things up, these messages would later appear at random on the System menu or supporting games.

Be as it may, Miiverse didn’t enjoy a long lifespan and it shut down in late 2017 (months after I finally managed to get a Wii U…).

Anti-Piracy and Homebrew

Welcome to the last section of this article (and thanks for making it this far!). Here is where we analyse how resilient the Wii U proved itself against the attempts of hackers. To be fair, no console (in this article series) has ever achieved 100% success rate. Yet, it’s the amount of time a console remains ‘unhackable’ and the effort required that will, to some degree, affect whether game studios will invest in the platform.

Having said that, let’s get on with the analysis!

Main targets

Nintendo had to defend three fronts with code-execution capabilities:

- The optical drive with its capacity of reading game discs.

- IOSU (running on Starbuck) with its exclusive ability to access most of the I/O and memory; and control Espresso.

- Cafe OS (running on Espresso) which is where the game runs on top of.

Protection implemented

First things first: The disc drive.

… Well, to this date, the drive hasn’t been publicly cracked. There have been reports about the development of ‘WiiKeyU’ [43], a drive emulator that can load disc images, but nothing ever reached the stores.

Considering the low adoption of Blu-ray drives throughout the Wii U’s lifecycle, I presume there wasn’t enough enthusiasm to crack the drive and/or deeply research its new protection methods. For the curious, the Wii U’s motherboard now authenticates with the drive in a similar way to the Xbox 360’s drive and, from there, all communication appears encrypted [44].

That leaves us with two remaining targets (IOSU and Cafe OS) and, this time, there’s plenty of research done.

Dedicated hardware

In general, there are many methodologies IBM and Nintendo employed to secure this console efficiently and cost-effectively.

First is a separation of concerns model present to limit hardware access between Espresso and Starbuck. This makes sure that if the main CPU (Espresso) is ever hijacked, the I/O is still protected somehow. Additionally, both CPUs contain a Memory Management Unit to disguise the physical memory map as they see fit.

Secondly, as I mentioned before, both Espresso and Starbuck bundle their own hidden Boot ROMs (with 16 KB and 4 KB, respectively) so they always come prepared with some degree of protection (RSA and AES encryption) before reaching out outer areas that are susceptible to tampering. In doing so, all subsequent code processed must be encrypted and only authored by Nintendo.

Thirdly, Starbuck disposes of considerable amounts of memory within Latte to boot up its operating system (IOSU) without having to reach out to external memory. This adds another layer of tampering protection.

Next, Starbuck embeds SHA-1 and AES-128 accelerators on its hardware to hash, encrypt and decrypt data without performance penalties.

Moving on, while Starbuck is technically an outdated ARM9 CPU, Nintendo enhanced it with a custom eXecute Never (XN) controller that restricts which memory locations Starbuck may execute [45]. The XN block fulfils the role of an NX bit.

Finally, encryption keys and certificates are stored in OTP memory inside Latte and both Espresso and Starbuck can seal access to each entry as soon as they are finished with it.

Chain of trust

As per any software involving signatures and encryption, there must be a hierarchy in place from which signatures are trusted.

From Espresso’s side, the master core always starts in a blank state, but as soon as it finishes executing the Boot ROM, it will only run binaries in the form of Ancast images (fail0overflow’s nomenclature). Ancast images contain a header signed by Nintendo using a RSA-2048 private key (which only Nintendo knows) and its payload (the actual program) is signed with an AES-128 key. The OTP block provides Espresso with the AES key to decrypt Cafe OS’ Kernel (the starting point of Espresso in Wii U mode). Afterwards, it’s up to Cafe OS to enforce the security model.

Starbuck, on the other hand, uses the Ancast image format for their bootloader stages after the Boot ROM. After IOSU is loaded up and running, one of its kernel modules called IOS-MCP is responsible for verifying and decrypting the AES key. Afterwards, the encrypted Ancast image and AES key are uploaded to MEM2 for Espresso to finish decrypting it and finally execute the payload.

Applications in Wii mode share the same nature, Espresso is provided with a separate key for decrypting the Wii System Menu or NAND Boot Program [46], thereby enabling Espresso to execute Wii applications without downgrading its security model. Starbuck is also provided with two extra keys in OTP to decrypt cafe2wii (in Ancast format) and Wii system updates (installed as part of a larger bulk of Wii U updates), respectively.

Operating System protection

To further complement the chain of trust, each operating system adds extra layers on top of it.

To start with, Cafe OS implements process isolation so programs under Espresso can’t fiddle with the memory space of their neighbours.

Moreover, the manipulation of Cafe OS applications is a complex process involving the two CPUs and different security mechanisms. To make a long story short, to install and/or boot up applications, the IOS-MCP kernel module is responsible for all the necessary routines [47]. Before being installed, the application’s signature (found in its header) is checked against the respective certificate stored in OTP, thereby making sure the application has been approved by Nintendo (as they are the sole possessors of the certificate’s private key). Afterwards, the title key of the application is decrypted using the OTP-stored Wii Common key, this allows Espresso to execute the binary later on (as the payload is still encrypted). Finally, whenever the application is launched at any time, Cafe OS’ Launcher is used to prepare the binary for execution and linking. Nevertheless, IOSU checks the signature again before transferring it to Espresso.

Finally, IOSU is aware of Espresso’s applications and only grants certain I/O permissions depending on the app’s entitlements. That means that particular applications like the Web browser will never have access to the SD card.

Flaws

At first glance, the Wii U’s security model looks more resilient and gratefully solves many deficiencies of its predecessor. However, it’s not without apparent flaws:

- Espresso, being an off-the-shelf CPU at its heart, only understands unencrypted code and, unlike the Xbox 360’s Xenon with its hidden encryption logic, Espresso will have to store the unencrypted data somewhere after decrypting it. In practice, that data is exposed on MEM2, meaning it’s at the mercy of external tampering.

- OTP lacks console-unique encryption keys (a big difference from the Xbox 360 and PS3), meaning that if they are ever extracted on a remote console, they will work on others.

- The Boot ROMs are secure media, but the code itself may contain vulnerabilities. Plus, the way the chain of trust is constructed makes the boot code a single point of failure.

- Data encryption/decryption relies on AES-128, a symmetric encryption system. While AES is faster than the asymmetric RSA, if the AES keys ever get extracted somehow, all encryption is therefore nullified.

- One of the pre-installed applications is a Web browser. Its rendering engine is a fork of WebKit and JavaScriptCore. The WebKit project provides a public report of security vulnerabilities continuously being discovered and fixed (as expected from any responsible and large open-source project). However, this also makes it an attractive starting point with many potential attack surfaces. To make matters worse, JavaScript engines tend to bypass memory execution protections as the engine needs to compile streams of JavaScript code on-the-fly (it’s worth emphasising that’s code coming from an arbitrary network server).

- Cafe OS lacks Address Space Layout Randomisation (ASLR), enabling exploits based on Return Oriented Programming (ROP).

- The Wii has already been completely hacked in advance, which leads us to think that vWii mode will share the same fate (and potentially spread to take over Wii U mode as well).