Supporting imagery

Models

Released on 15/11/2001 in America, 22/02/2002 in Japan and 14/03/2002 in Europe.

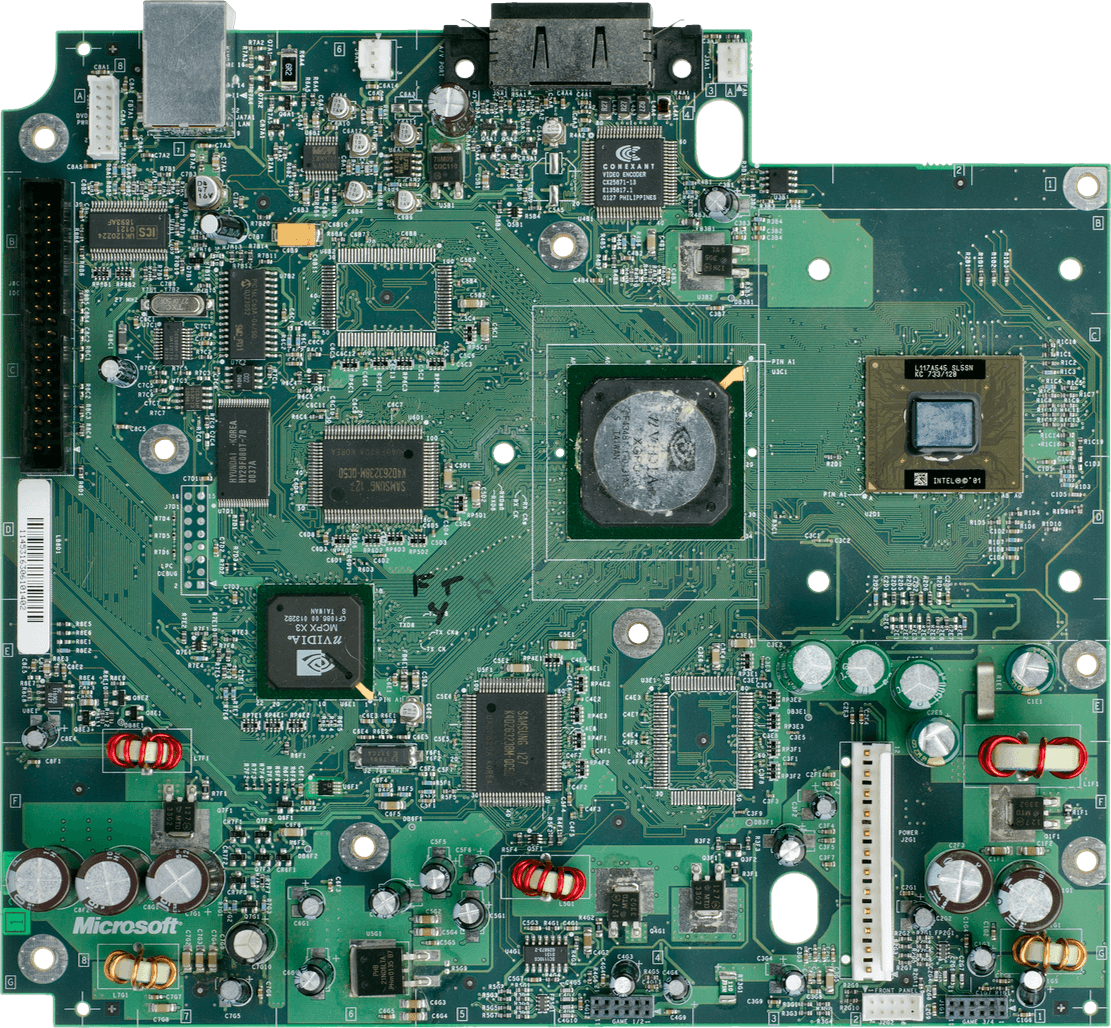

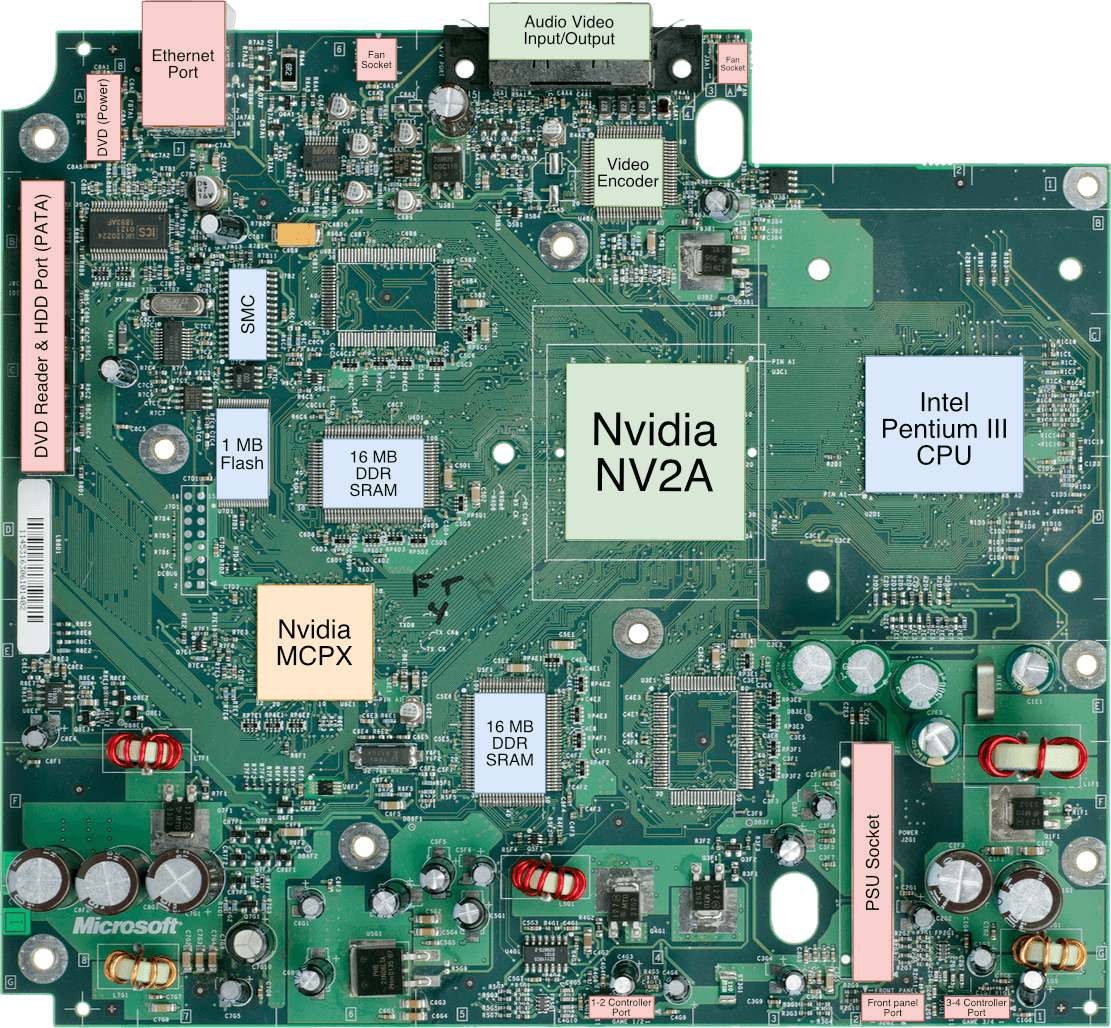

Motherboard

Showing first revision.

Controllers are plugged using a separate daughterboard.

Missing SDRAM chips are on the back and there are four unpopulated SDRAM slots.

Diagram

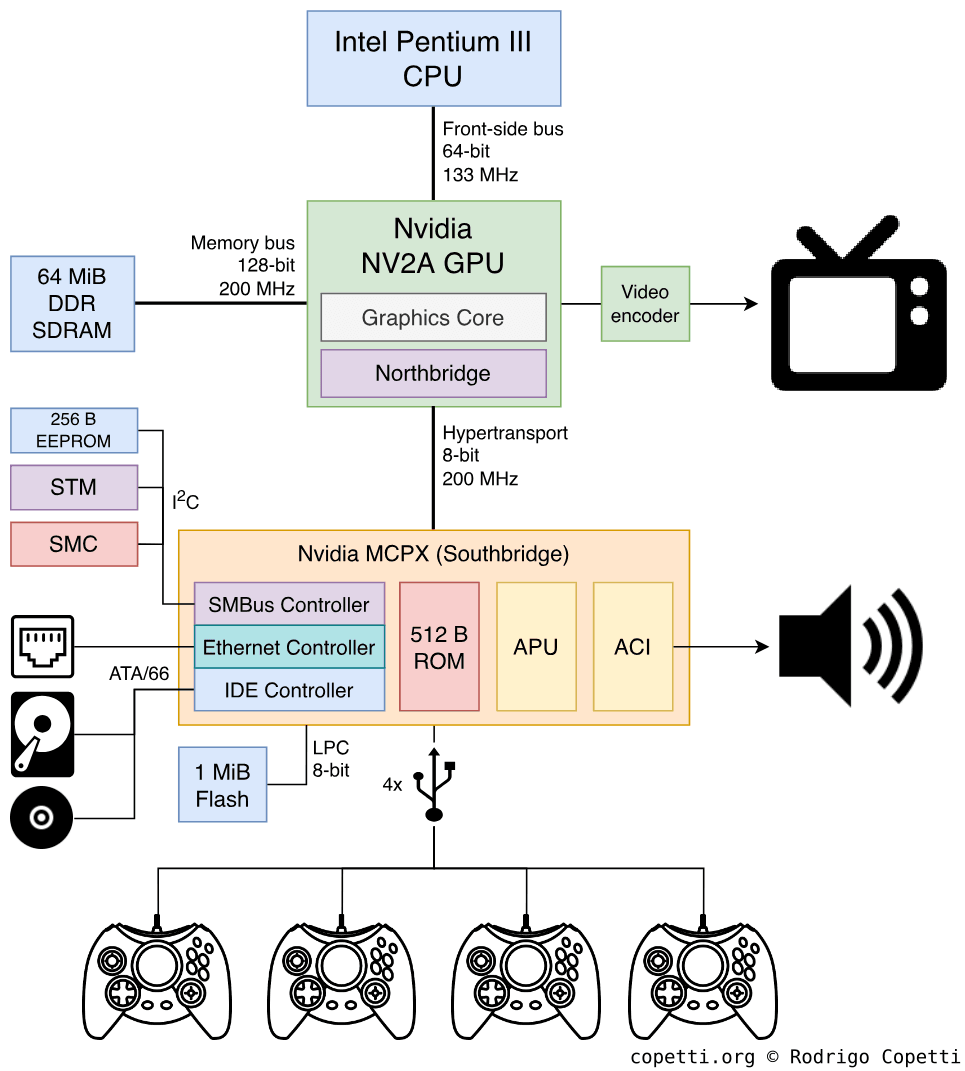

Each controller is connected to a separate USB hub.

A quick introduction

It seems that Microsoft has decided to pick up where Sega left off. Their offer? A system with familiarities appreciated by developers and online services welcomed by users.

Please note that to keep consistency with other sources, this article separates storage units between the metric prefix (i.e. megabytes or ‘MB’) and the standardised binary prefix (i.e. mebibytes or ‘MiB’), thus:

- 1 MB = 1000 KB

- 1 MiB = 1024 KiB

… and so forth.

Reading tips

Some months after writing this, I’ve realised this is one of the densest write-ups I have done. There’s just a lot of stuff happening inside the Xbox and I have tried to mention most of it.

Now, if you’re really interested in understanding this system but find this article difficult to follow, my advice to you is: Take your time, the article is not going anywhere. Focus on what you like, read at your own pace, check out the links on the ‘Sources’ section for support and finally, don’t put pressure on yourself, there’s no exam!

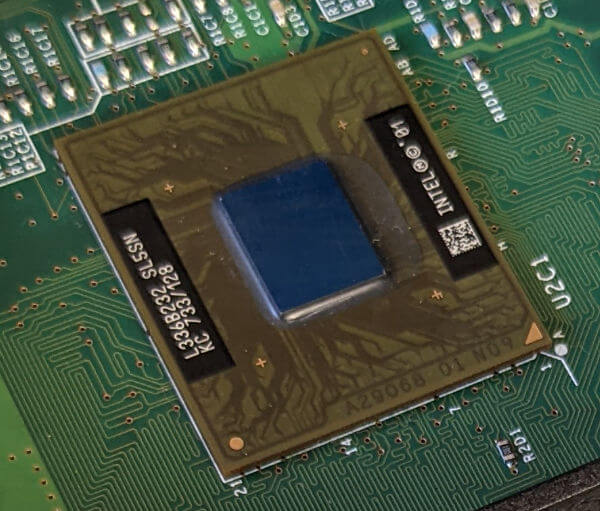

CPU

The processor included in this console is a slightly customised version of the famous Intel Pentium III (an off-the-shelf CPU for computers) running at 733 MHz. With this, one can assume this console is just a PC behind the scenes… I won’t tell you the answer, but I promise that at the end of the article you will be able to reach your own conclusion.

Anyhow, Pentiums, along with other lines of CPUs designed and manufactured by Intel, were incredibly popular in the computer market. Such was Intel’s market share that they became the de-facto reference point for quality: As a typical user, if you wanted a good computer and had the budget, you only had to look for something carrying an Intel CPU. We all know by now that there are more factors involved, but that’s what the marketing guys at Intel managed to project.

Technical information

Now that we positioned Intel on the map, let’s go back to the topic of this console. During my research, I was expecting to find documentation with the level of depth as other CPUs (MIPS, SuperH, ARM, etc), but instead, I stumbled across an excessive amount of marketing terms that only diverted my search. So, for this article, I came up with a structure to organise all the necessary information which will help to understand how this CPU works. Furthermore, I will try to introduce some terminology that Intel used to brand this CPU.

Having said that, let us take a look:

Branding

First things first, the Xbox’s CPU is identified as a Pentium III. So what does this mean? Back then (early noughties), the Pentium series represented the next generation of CPUs. They were the ‘new high-end’ that grouped all the fancy technology that made computers super-fast, plus it helped buyers decide which CPU they had to buy if they wanted the best of the best.

Pentium III replaced Pentium II, which in turn replaced the original Pentium. Moreover, when the first Pentium came out, it replaced the 80486, which in turn replaced the 80386… You get the idea. What matters is that ‘Pentium’ is mainly a brand name, it’s not directly associated with its inner workings. Therefore, we must go deeper!

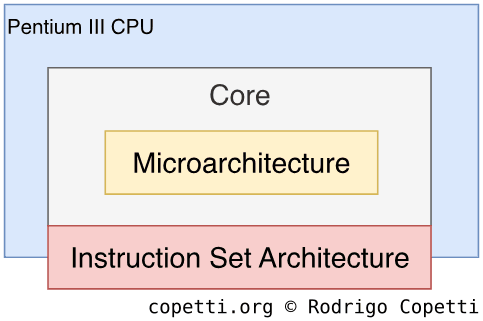

To dive further and not get lost in the way, I have catalogued the information into three sections which combined, make up the chip. The first the Instruction Set Architecture or ‘ISA’ (the group of instructions used to command the CPU), Microarchitecture (how is the ISA implemented in silicon) and the Core (what set of components are used to package the microarchitecture to form the specific CPU model).

The ISA

Indeed, once I mention ‘Intel’ it’s a matter of time before I introduce the famous x86, its instruction set.

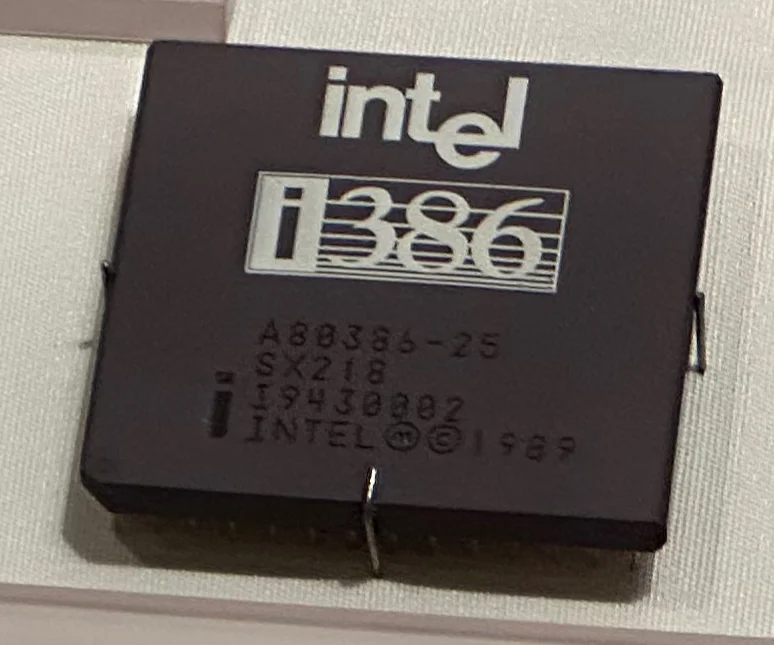

The first form of x86 debuted with the release of the Intel 8086 in 1978, a 16-bit CPU. Afterwards, the ISA was constantly expanded with more instructions as more Intel CPUs were released (80186, 80286 and so on) [1]. Consequently, x86 started to fragment as more ground-breaking features were added (i.e. ‘protected mode’ and ‘long mode’). To tackle this, modern x86 applications commonly target the 80386 ISA (also called IA-32 or i386) as a baseline, which among other things, operates in a 32-bit environment.

Subsequently, Intel enhanced the IA-32 with the use of extensions, meaning the new functions may or may not be included in an IA-32 CPU. Programs query the CPU to check if a specific enhancement is present. The Xbox’s CPU includes two extensions:

- MMX (Multimedia Extension): Adds 57 SIMD instructions and 8 64-bit registers (integers only) that can speed up vector operations.

- SSE (Streaming SIMD extension): Another SIMD-type extension that addresses the criticism of MMX (lack of floating-point support and unable to use the floating-point unit in parallel). It adds 56 new instructions and eight 128-bit registers (called ‘XMM’) that hold four 32-bit

floats.

The good news is that, since the console will always have the same CPU, programmers can optimise their code to exploit these extensions as they will always be present.

The Microarchitecture

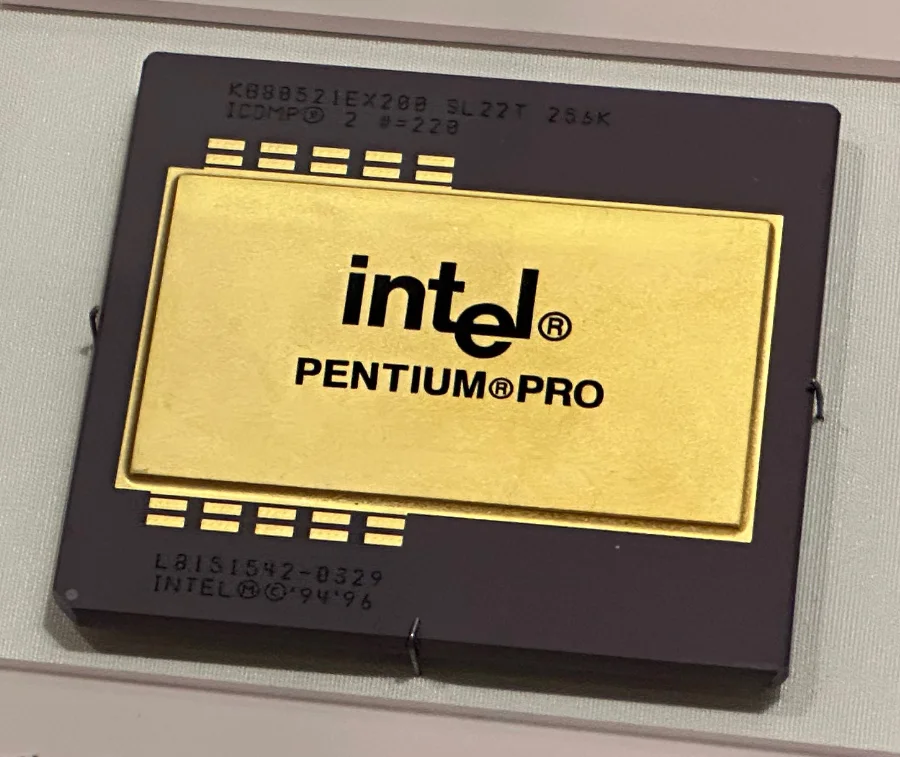

When it comes to building a circuit that can interpret x86 instructions, Intel has come up with so many different designs for their CPUs. Some designs were featured with the release of a new Pentium Series (i.e. Pentium 4) while others were featured when Intel released an ‘enhanced’ version of a Pentium (such as the ‘Pentium Pro’). Nevertheless, since the release of the first Pentium, the CPU model and microarchitecture no longer carry the same name. For example, the 80486 uses the 80486 microarchitecture (and no other), however, the original Pentium has the ‘P5’ microarchitecture.

Now, the Xbox CPU, along with the rest of Pentium III processors, use the P6 Microarchitecture (also known as ‘i686’). This is the 6th generation (counting from the 8086) which features:

- A massive 14-stage pipeline: Meaning up to 14 instructions can be processed in parallel. On the other side, individual instructions may take a lot more cycles to complete. See a previous explanation.

- Out-of-order execution: If possible, the CPU re-orders the sequence of instructions to increase efficiency and performance.

- Dynamic execution: Since the P6 is an out-of-order and superscalar design. The traditional branch predictor is now combined with other techniques (‘speculative execution’ and ‘data-flow analysis’) to take advantage of the new capabilities. In doing so, it reduces pipeline stalling even further.

Having said that, take a closer look at these features. It so happens they are very similar to previous consoles, however, the other CPUs are very different in terms of design compared to Intel ones. Historically, one could argue that the design of the x86 would’ve never allowed Intel to produce, let’s say, a pipelined CPU. Yet they managed to do so, so let us see why…

CISC or RISC

The competition happens to feature CPUs designed around the RISC guidelines, whereas Intel’s x86 is not, thereby being placed in the CISC group. RISC CPUs are known for having an intentionally simplified design compared to CISC CPUs. This includes, for instance, implementing a load–store architecture, which only provides instructions that operate values from registers (as opposed to operating directly from memory).

One of the advantages of RISC processors is that their simplistic approach enables its CPUs to be designed with a modular sense, which in turn can be exploited to improve performance with parallelism techniques. This is why we have seen CPUs like MIPS and PowerPC debuting pipeline stages, superscalar designs, out-of-order execution, branch prediction, etc. On the other side, CISC processors predate RISC ones and the former aimed to solve different needs. Consequently, their designs are not as flexible as RISC CPUs.

Back to the original question, the P6 is an interesting design, because while this CPU only understands a CISC instruction set (x86), a subset of its opcodes is interpreted using microcode. Most importantly, the unit that executes microcode is built around the load-store model [2]. This is because the P6 architecture was authored by the former engineers of the Intel i960 (a once-promising RISC CPU by Intel). All in all, this has enabled Intel to gain similar advantages to RISC processors without breaking compatibility with the historic x86 ISA. It’s fair to say that as time passed by, terms like ‘CISC’ and ‘RISC’ have become too ambiguous to categorise any modern CPU.

As a side note, microcode is already embedded in the silicon but it can be patched, allowing Intel to fix its CPUs after production whenever a bug or a security vulnerability is discovered. If you have read previous articles (i.e. N64 or PS2), bear in mind that Intel’s microcode is not publicly accessible (let alone documented) and Intel is its sole ‘maintainer’.

The Core

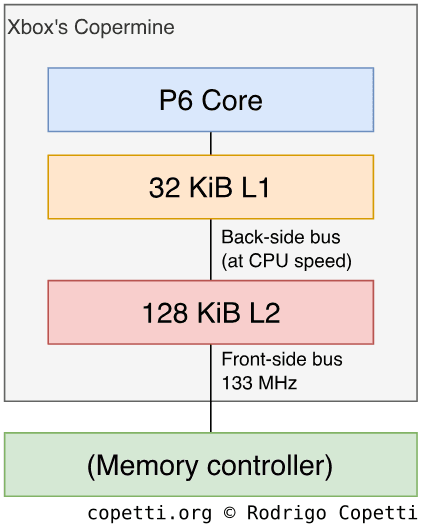

Intel shipped numerous chips that implemented the P6 microarchitecture. The Xbox includes one model called Coppermine. It was branded as the second revision of the Pentium III (replacing the ‘Katmai’ core) and features the following components:

- 32 KiB L1 cache: Divided between 16 KiB for instructions and 16 KiB for data.

- Integrated 128 KiB L2 cache: This is odd since the off-the-shelf Coppermine has 256 KiB of L2 [3]. In fact, the Coppermine128 (found in the Intel ‘Celeron’ brand, the low-end Pentium alternative) has the same amount of L2 [4]. Hence, this was probably done to reduce manufacturing costs and keep this console at a competitive price.

- 133 MHz Front-side bus: This is the bus that connects the L2 cache with the memory controller, we’ll see more about it later on.

- Intel names it ‘Front-side bus’ to distinguish it from another bus that connects L2 (external cache) with L1 (internal cache). The latter bus is called ‘Back-side bus’… and it’s an unfortunate name to use in the UK.

Coppermine also adds two ‘enhancements’ over their original implementation of L2 cache, these are the Advanced Transfer Cache and the Advanced System Buffering. To sum them up, L2 cache is on-chip and their buses are wider, which helps to reduce possible bottlenecks in the Front-side bus.

Finally, the chip uses the ‘Micro-PGA2’ socket fit on the motherboard, but like any other console, the Xbox has it soldered with a Ball Grid Array or ‘BGA’.

P6 and the end of Pentium numbers

Here’s a bit more history. After the years of the P6, Intel planned to succeed it with the ‘NetBurst’ microarchitecture (featured in the Pentium IV). However, the line of succession also ended there. Even though NetBurst implemented many contemporary techniques [5], it also suffered from excessive power consumption, heat emission (an average of 85 W [6]) and scalability issues - all of which impeded the design from being continued any further.

Consequently, this prompted an Intel team in Israel to revisit their low-powered P6 CPU - the ‘Pentium M’ - and develop a more powerful successor. The first result was the Yonah core, a slight improvement of the P6 design branded as Core Solo or Core Duo. With it, power dissipation dropped to reasonable numbers (between 27 W [7] and 31 W [8], depending on the variant). Months later, the follow-up Core microarchitecture became the flagship successor of P6 (and NetBurst) and, confusingly enough, reached the shelves in the form of the Core 2 CPU line. Over the years, subsequent microarchitectures improved on many aspects, but they also managed to re-incorporate forgotten elements from NetBurst without repeating the same mistakes.

On a curious note, I wonder if the naming of the Yonah core is meant as a metaphor for the Book of Jonah, particularly connecting the event where the prophet, in the end, managed to correct his path to save the city of Nineveh. Though it’s also possible I’m overthinking this.

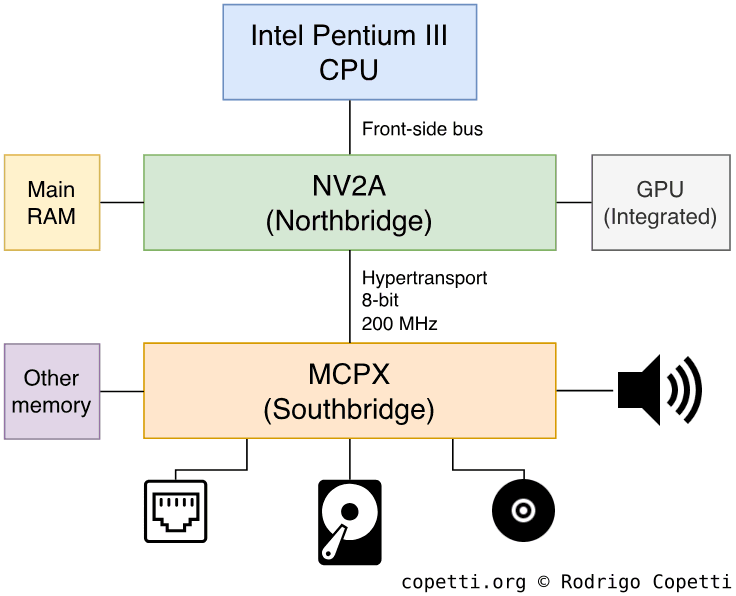

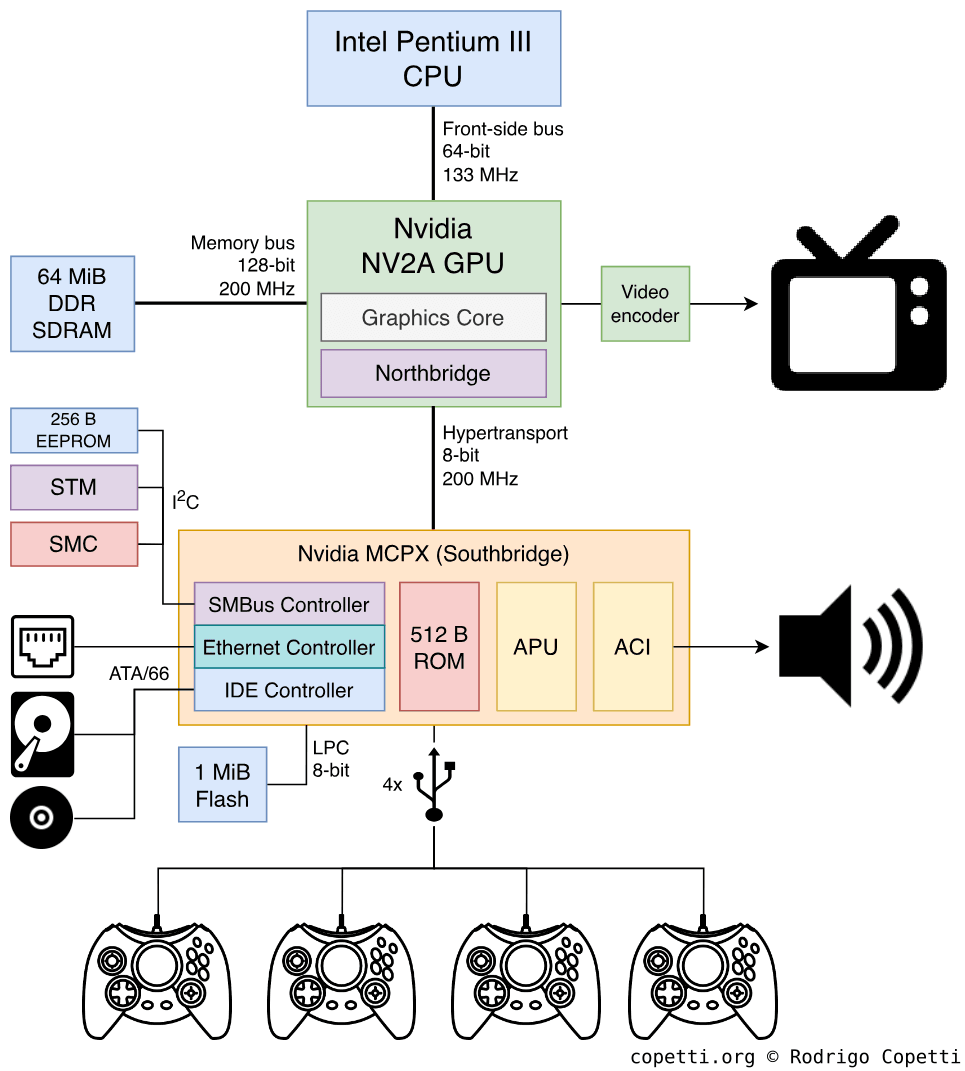

Motherboard architecture

At some point in the history of the PC, motherboards grew so much in complexity that new designs had to be developed from the ground up to efficiently tackle emerging needs.

The new standard developed relied on two dedicated chips to handle most of the motherboard functions. These chips are:

- The Northbridge: Serves as a memory controller and interfaces the GPU.

- The Southbridge: Interfaces the rest of I/O (i.e. USB, ATA/SATA, PCI, etc)

The combination of these chips is called chipset and they are important enough to condition the capabilities and performance of a motherboard. The Xbox, being so close to a PC, includes two chips as well: The NV2A, a combination of Northbridge and GPU; and the MCPX which handles the rest of I/O.

Both chips are interconnected using a specialised bus called the HyperTransport. It’s worth pointing out that some PC motherboards also included this technology, just with a different brand (nForce MCP-D).

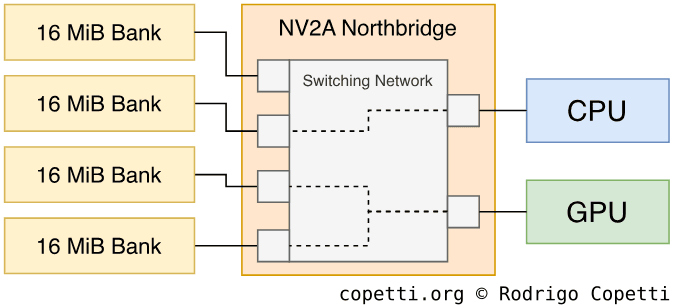

Memory layout

The Xbox includes a total of 64 MiB of DDR SDRAM, this type of RAM is very fast compared to what the competition offers. However, it’s also shared across all components of this system. Hence, once more, we find ourselves in front of another unified memory architecture or ‘UMA’ layout.

We have previously seen how troublesome this design can be sometimes. Nonetheless, programs can address this issue by spreading their data between different banks of memory. NV2A implements a switching network that enables different units (CPU, GPU, etc) to concurrently access them [9] [10].

Furthermore, the console features an internal hard disk, and it so happens to be set up with three partitions of 750 MiB each reserved for temporary storage. The CPU can offload some of its data from main RAM, then upload it back whenever it’s needed. Bear in mind this is a manual process and does not involve virtual RAM.

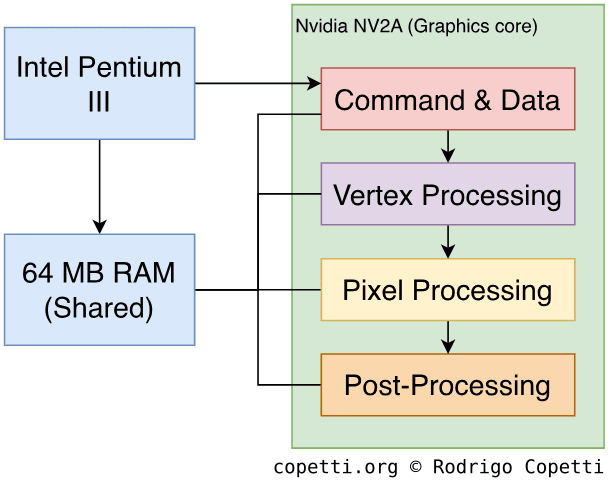

Graphics

As we’ve seen before, the graphics processor resides in the NV2A chip and, just like MCPX, it is manufactured by Nvidia.

This company has been in the graphics business for a long time, their GeForce series are one of the most popular GPU brands in the computer market, directly competing against the Radeon series from ArtX/ATI. Overall, this provides good leverage on the quality of graphics found in the Xbox, considering it’s Microsoft’s first attempt in the console market.

It all seems reasonable, but was it really a certain decision to make back then? It’s easy to rely on present history to find out why Microsoft chose Nvidia over other popular brands from the time (3dfx, PowerVR, S3, etc), but if we read more about the competition back then, the panorama of options made it much more complex.

For instance, 3dfx’s popular ‘Voodoo 2’ series had ~70% of the market share in the PC market by the end of the 90s [11], while Nvidia was struggling to promote adoption of the new ‘GeForce 256’ (the first of the GeForce series). After this, Microsoft’s choice now sounds more like a risk than a safe bet, but as we know by now, this risk eventually paid off.

Nvidia was NOT the #1 player they are now, in 1999. They were in trouble. The new GeForce architecture was still young and lots of people didn’t like it. Now it seems forgone. But you’d need to research that history to know that, and why I had to fight to use it. I was right but I didn’t know I was right; I was very worried.

– Seamus Blackley (Co-author of the original Xbox)

In the following section, we’ll examine the inner workings of this chip. Now, I’m afraid we find ourselves mixed in a lot of terminology and marketing terms just like the CPU section, but fear not! I’ll start with the basics.

Architecture and design

The GPU core found on the NV2A is based on the popular ‘GeForce3’ series of GPUs [12] [13], it’s also referred to as NV20 in Nvidia’s technical documents.

Please note that, while the pipeline of the Xbox’s GPU is based on the NV20 architecture, the NV2A has some modifications that are not compatible with the rest of the NV20 series (most importantly, it has been adapted to work in a UMA environment).

The units analysed contain a lot more features that go beyond the scope of this article, so I recommend checking out the sources/references if this section catches your attention. Also, since graphics-related terminology is constantly evolving (which can lead to some confusion), I’ve decided to rely on the terms used by Microsoft/Nvidia during the years of the Xbox, so remember this if you plan to read more graphics-related articles from other sources.

Having said that, let’s take a look at how frames are drawn in the Xbox. Some explanations are very similar to GameCube’s Flipper, so you may benefit from reading that article as well in case you struggle to follow this one.

Commands

First and foremost is explaining how the GPU can receive commands from the CPU. For that, the GPU contains a command processor called PFIFO that effectively fetches and processes graphics commands (called Pushbuffer) in a FIFO manner, the unpacked commands are subsequently delivered to the PGRAPH (the block in charge of graphics processing) and other engines.

Like Flipper, geometry doesn’t have to be embedded in the command. PGRAPH provides many ways to submit graphics data. For instance, the CPU can allocate a buffer in RAM containing vertex data and then instruct the GPU to fetch them from that location. This approach can be efficient, as it prevents sending duplicated geometry.

The next explanations happen in PGRAPH.

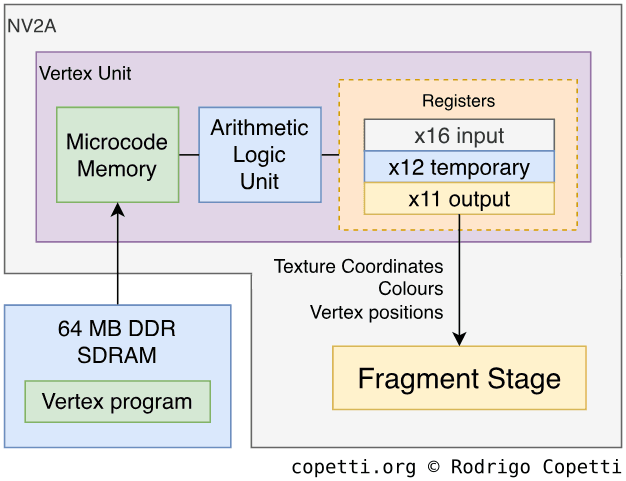

Vertex

This is an interesting section for this GPU in particular. At this stage, the GPU provides the ability to apply vertex transformations to our geometry. We’ve already seen this feature with Flipper, but unlike that GPU, this one uses a programmable engine. This means that developers may specify which vertex operations are performed and how, as opposed to relying on a predefined program. Although, the NV2A can also operate in ‘fixed’ mode, if required.

This stage is handled by a Vertex Unit and the NV2A features two of them. Each can load a program containing up to 136 instructions (also called microcode). This program is referred to as vertex program and it’s loaded at runtime. A vertex program can perform the following operations [14]:

- Arithmetic operations (i.e. addition, multiplication, minimum, etc).

- This includes ‘helper functions’ to assist graphics-related tasks, such as dot product.

- Vertex Swizzling (Rearrangement and/or duplication).

In a nutshell, the vertex unit processes vertices by manipulating them in its registers. In other words, once the program is loaded, 16 read-only registers (called ‘input registers’) are initialised with the attributes of a vertex (each vector contains four components). Afterwards, the unit performs the set of operations (instructed by the program) using the input registers. Furthermore, 12 writable registers and up to 196 constants are provided to assist the computation. Finally, the resulting vertex is stored in another block of 11 writable registers (each one limited to a specific purpose), which are passed on to the next stage. This process is repeated for every vertex received.

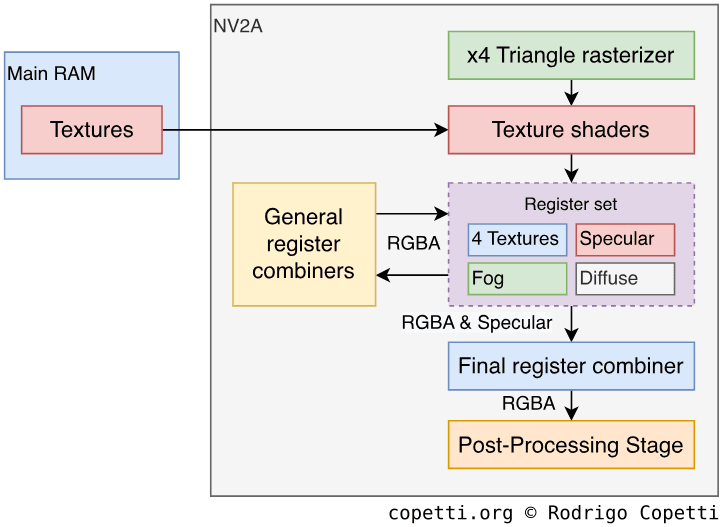

Pixel

At this stage, vertices are transformed into pixels. The process starts with a rasteriser that generates pixels to draw each triangle. The NV2A’s rasteriser can generate four pixels per cycle.

Afterwards, 4 texture shaders are used to fetch textures from memory [15], these also offer to automatically apply anisotropic filtering, mipmapping and shadow buffering. The latter one is used to test whether a pixel is visible or overshadowed by the lighting source, so the correct colour can be applied. At this point, the GPU also offers to perform clipping and an early Z-test (the NV2A compresses the Z-buffer four times its original size to save bandwidth, contributing to a lot of performance improvements).

The resulting pixels are stored in a set of shared registers and then cycled through 8 register combiners, where each one applies arithmetic operations on them. This process is programmable with the use of pixel shaders (another type of program executed by the GPU) [16]. At each cycle, each combiner receives RGBA values (RGB + Alpha) from the register set [17]. Then, based on the operation set by the shader, it will operate the values and write back the result. Finally, a larger amount of values are sent to the final combiner which can exclusively blend specular colours and/or fog.

Register combiners are programmable in a similar nature to the Texture Environment Unit. That is, by altering its registers with a specific combination of settings. In the case of the Xbox, the PFIFO reads pushbuffers to set up PGRAPH, which includes the register combiners and texture shaders.

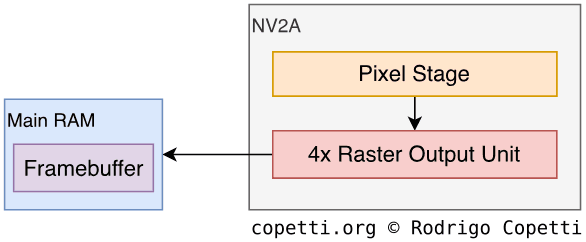

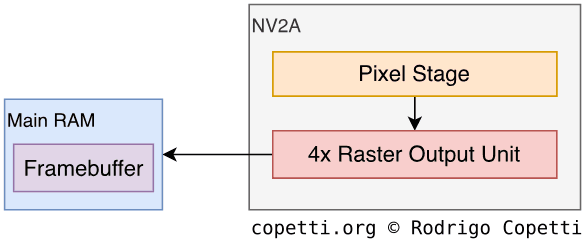

Post-processing

Before the pixels are written to the frame-buffer, the NV2A contains four dedicated engines called Raster Output Unit or ‘ROP’ which perform necessary tests (alpha, depth and stencil) using allocated blocks in main memory. Finally, batches of pixels (four per cycle) are written back only if they pass these tests.

Moreover, the frame-buffer can be anti-aliased using a technique called multisampling [18]. Essentially, this technique samples the edges of polygons multiple times with different offsets added in the process. Afterwards, all samples are averaged to form the anti-aliased image. This approach replaced the previous (and more resource-hungry) anti-aliasing function called ‘supersampling’, used by previous Nvidia GPUs.

The importance of programmability

I find it pivotal to emphasise the significance of the new programmability model that Nvidia provided to developers. Years ago, most of the graphics pipeline was computed by the CPU, leaving the GPU to accelerate rasterising operations. With the introduction of ‘shaders’ (referring to both pixel shaders and vertex programs), programmers can take advantage of the resources of the GPU to accelerate many computations in the pipeline, offloading a great amount of work from the CPU.

The concept of ‘shaders’ was introduced by Pixar in 1989 as a method to extend Renderman [19], their pioneering software used for 3D rendering. This was back in the time when 3D graphics were mainly handled by industrial equipment. Later on, we saw how certain consoles incorporated similar principles, but it wasn’t until Nvidia released their GeForce3 line, that shaders became a standard in the consumer market.

Thanks to vertex programs, the GPU can now accelerate model transformations, lighting calculations and texture coordinate generation. The latter is essential for composing Higher Order surfaces. With this, the CPU can concentrate on providing better physics, AI and scene management.

In the case of pixel shaders, programmers can manipulate and blend textures in multiple ways to achieve different effects such as multi-texturing, specular mapping, bump mapping, environment mapping and so on.

A new programming concept that emerges thanks to this approach is the General Purpose GPU or ‘GPGPU’, which consists of assigning tasks to the GPU that would have been exclusively done by the CPU. So not only the GPU has taken over most of the graphics pipeline, but now can act as an efficient co-processor for specialised computations (i.e. physics calculations). This is a new area that will evolve as GPUs become more powerful and flexible. However, the NV2A was already able to achieve this thanks to a combination of hardware capabilities (vertex & pixel shaders) and specialised APIs developed (OpenGL’s ‘state programs’).

I have a feeling that shaders will be regularly revisited in future articles. Please remember that in this article, however, they may be considered a bit ‘primitive’ and some people may argue that the pixel shaders are not even ‘shaders’ (compared to what GPUs offer nowadays).

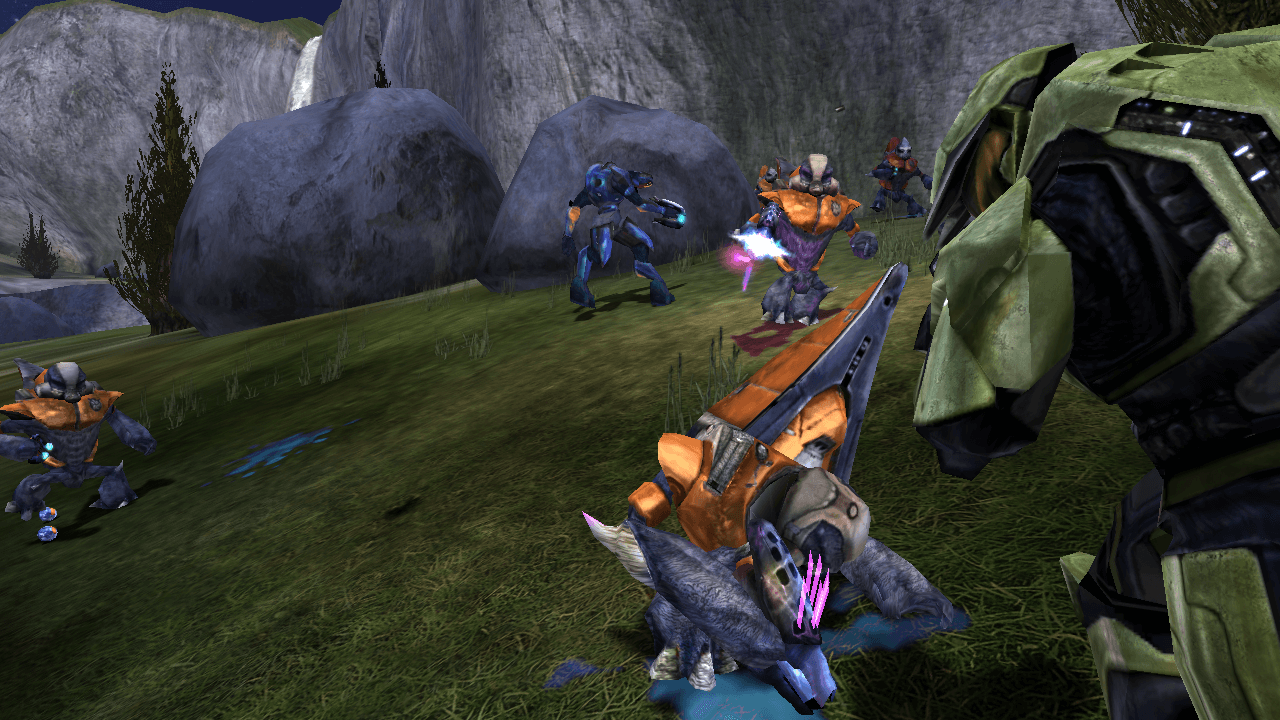

The Xbox’s frame

The standard resolution of games is 640x480, this is pretty much the standard in the sixth generation. Although, this constraint is just a number: The GPU can draw frame-buffers with up to 4096x4096, yet it doesn’t mean the hardware would provide acceptable performance. On the other side, the console allows configuring its screen setting globally, which may help to promote pioneering features (i.e. widescreen and ‘high resolution’) instead of waiting for developers to discover them (as it happened with the Gamecube/Wii).

The video encoder, on the other hand, will try to broadcast whatever there is on the frame-buffer in a format your TV will understand. That means that widescreen images will become anamorphic unless the game outputs in HD (i.e. 720p or 1080i, which only a few games do).

That being said, what kind of signals does this console broadcast? Quite a lot. Apart from the typical PAL/NTSC composite, the Xbox offers YPbPr (requiring an extra accessory to get the ‘component’ connectors) and RGB (both SCART and VGA compliant). All in all, very convenient without requiring expensive adapters and whatnot.

Audio

The audio subsystem of this console was heavily influenced by the technology of professional audio equipment and ATX motherboards, although it does contain some peculiar parts. The MCPX includes two audio components, the Audio Processing Unit and the Audio Controller Interface’.

The Audio Processing Unit or ‘APU’ is the dedicated audio processor and is composed of three sub-components:

- The Voice Processor or ‘VP’: A specialised circuit that can synthesise 256 voices at a sampling rate of 48 kHz. It also includes two DAHDSR envelope controls and various filters. Furthermore, 64 voices can be 3D (as opposed to Stereo or Mono). At the end, the processor mixes and outputs the voices through 32 channels, where groups of 8 channels have their own volume control.

- The Global Processor or ‘GP’: A programmable DSP used to process the audio data from the VP and apply various effects on it.

- Not all the channels coming from the VP have to be fed here, instead, specific groups can be sent to apply specific effects (i.e reverb) exclusively on them.

- The Encode Processor or ‘EP’: As the name indicates, it generates the final stereo signal coming from the GP and stores it in main RAM.

- Notice the operations of the EP can also be carried out by the GP, but having a separate component for encoding enables the console to strive for better audio encoding techniques, such as Dolby Digital.

The APU only processes audio data but can’t output it. The latter is the job of the ACI, which reads the audio data in RAM, decodes it and sends the resulting PCM stereo sample (16-bit resolution with a sampling rate of 48 kHz) through the audio output.

I/O

As I mentioned before, we have a ‘Southbridge’ subsystem which concentrates all I/O access. This Southbridge is implemented by the MCPX chip.

Incidentally, the MCPX derives from its PC counterpart called nVidia nForce Multimedia and Communications Processor or ‘MCP’. This is found on motherboards using the nForce 220/415/420 chipset [20].

External interfaces

The console includes the following external connectors:

- 4 USB 1.1 ports: Used to connect the controllers, however, the external shape of the port is modified to only allow Xbox controllers.

- These ports also contain an extra pin called ‘Video Sync’ to connect peripherals that interact with the screen.

- 10/100BASE-TX Ethernet port: Used for online services (more details later). The actual Ethernet function is performed by a separate transceiver found in the motherboard.

Internal interfaces

The MCPX also provides the following interfaces and protocols used to interconnect different subsystems:

- SMBus: Also referred to as I²C, it’s a serial interface that connects these components:

- System Management Controller or ‘SMC’: Manages multiple services, such as power, temperature and fan control. It’s actually a PIC16LC microcontroller.

- System Temperature Monitor or ‘STM’: A digital thermometer (ADM1032) used by the SMC to detect overheating.

- A 256 B EEPROM: A re-writable ROM that stores unique identifiers (serial number, region, Ethernet MAC address, etc).

- Video Encoder: The encoder is primarily connected to the GPU but controlled through the SMBus.

- IDE Controller: This is a standard protocol widely used on PCs to communicate with Hard drives, optical readers and so forth. A single wide ribbon cable is used to connect the motherboard with the DVD drive and the HDD.

- Low Pin Count or ‘LPC’ bus: This is another interface borrowed from the PC, but instead of connecting the good old PC BIOS, it communicates with a Flash ROM, which in turn stores the equivalent of a BIOS. The Flash is 1 MiB large.

The controller

The Xbox came with a bulky controller called The Duke, its set of inputs isn’t any different from what the other competitors had… except for the usage of analogue circuitry (8-bit wide) on the face buttons, allowing games to detect ‘half-presses’ from most of the button set. On the other side, the Duke was so widely criticised that Microsoft replaced it with a new revision called Controller S months after the release of the console.

On closer inspection, both controllers did include something special: Two Memory Unit slots to plug in a proprietary memory card, enabling to share saves between consoles. Upon realising this, I instantly assumed this feature was inherited from a previous competitor. However, days after publishing this article, I sent it to Seamus Blackley, the co-creator of this console, who quickly replied with very interesting comments. Regarding the Dreamcast similarities, he told me:

The relationship to Dreamcast is just historical bias. That was accidental.

– Seamus Blackley

A required adapter

Another interesting fact to mention about these controllers is that they can only be plugged in using a shape adapter referred to as breakaway dongle, this was designed in an effort to prevent accidents when someone tripped over.

I think they also planned for where an Xbox was on a high shelf and yanking the controller would pull the whole heavy console down on some kid’s head.

– Xbox user

Operating System

All right, let’s start by addressing the elephant in the room.

Does it run Windows?

I’m afraid this is a yes and no answer: There is a ‘Windows’ present in this console, but not in the form conventional PC users would expect.

First things first, the Xbox’s operating system is composed of a Kernel and userland applications (i.e. the Dashboard). These are stored in the 1 MiB Flash ROM and the HDD, respectively.

The Kernel borrows a significant codebase from Windows 2000’s kernel [23] (which, in turn, is based on the modern Windows NT architecture). The result is a stripped-down Windows 2000 kernel that only embeds the necessary components for the Xbox hardware. These are finally compressed and packaged in a single executable [24] for optimal memory efficiency. All in all, you can think of it as a highly-optimised Windows machine exclusively designed for gaming.

It’s worth pointing out that the Xbox project was headed by the DirectX team [25]. Thus, its origin is unrelated to the Windows CE team that brought its APIs to the Dreamcast.

Boot Process

As with Pentium machines, upon booting up the system, the CPU will start executing instructions found at the reset vector (address 0xFFFF.FFF0). For the Xbox, this address points to a hidden ROM found in the MCPX (more details are explained in the ‘Anti-Piracy and Homebrew’ section). The MCPX contains routines to set up the security system and continue booting from the Flash ROM instead. Inside the Flash ROM, the Xbox will initialise its hardware, boot the Kernel and show the splash animation.

During security initialisation, the CPU turns into protected mode. This is critical since x86 CPUs always start up in real mode to maintain compatibility with the first processor (the Intel 8086), however, if programmers need to access the modern features of the CPU (such as being able to access more than 1 MiB of memory), they have to manually enable them by switching to protected mode.

When the Kernel loads, it injects microcode into the CPU (not to program it, but rather to update it). Finally, the Kernel looks for the presence of a valid DVD disc. If there is one, it runs it. Otherwise, it will load a user-interactive shell stored in the Hard Drive.

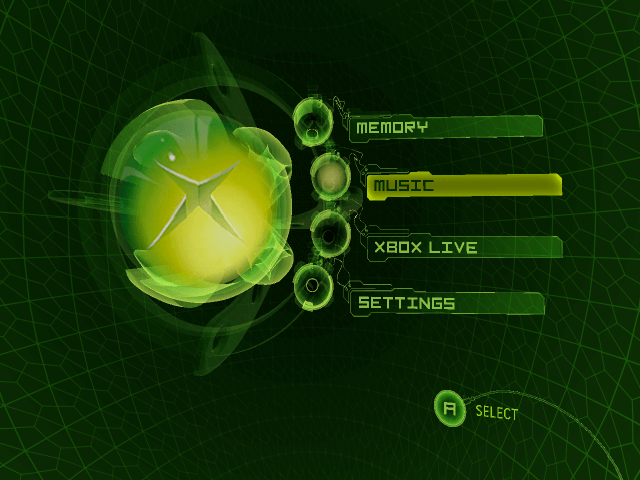

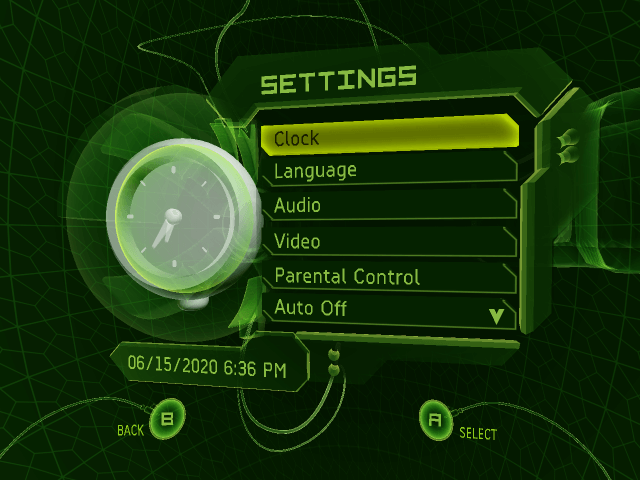

The green screen

Let’s take a look now at the program that the Xbox loads when there isn’t a game disc inserted: The Dashboard.

Interactive shell

The dashboard is not very different in terms of functionality compared to the PlayStation menu, or the GameCube’s IPL. It essentially includes all the functions typical users would expect, like being able to tweak some settings, moving saves around, playing DVD movies or CD audio; and so forth.

One thing worth mentioning is that the Dashboard also allows to rip music from an audio CD and store it in the HDD. This music can be subsequently fetched from any game to ‘personalise’ its soundtrack. Far out!

Updatability

Well yes, this is the first console of its generation to be officially updatable, but only the contents of the HDD are writable. The Kernel part (in the Flash ROM) can’t be re-written, but the system can patch it after it’s loaded in memory. Kernel patches are therefore stored in the HDD.

Updates are distributed through retail games and/or downloaded by the system after connecting to the Xbox Live network service (more about it later on).

Some updates enhanced the functionality of the system. For instance, the first Xbox units didn’t include Xbox Live, so games embedded the required files in the form of an update to install that service. Other updates focused on fixing security vulnerabilities.

Games

This part may be a bit confusing, mainly due to the lack of low-level documentation compared to other consoles. It seemed that Microsoft/Nvidia really wanted developers to use their libraries and forget about everything else. It’s an interesting strategy nonetheless.

In any case, I tried to document it as informative as possible, without going into too much depth.

Development ecosystem

Game development in this console is very complex in terms of libraries, terminology and so forth. So I have separated it by frameworks.

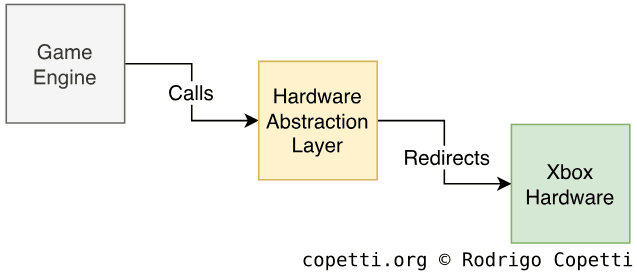

Hardware Abstraction

We have seen how elements like a ‘programmable coprocessor with microcode’ tend to come with a lot of fanfare at first, but slowly dissipates once developers discover the real complexity of the new hardware.

From the developer perspective, I think one of the selling points of this console was the inclusion of popular high-level libraries that could efficiently manage low-level functionality. Microsoft and Nvidia’s strategy consisted in, instead of documenting every low-level aspect of their hardware, they just provided a fully-functional hardware abstraction library that could perform the operations developers would expect to find without requiring complete knowledge of the inner workings of the hardware.

There are multiple SDKs available to develop for this console, some ‘official’ and restrictive, while others ‘not-so-official’ but flexible. We’ll take a look at the most popular ones.

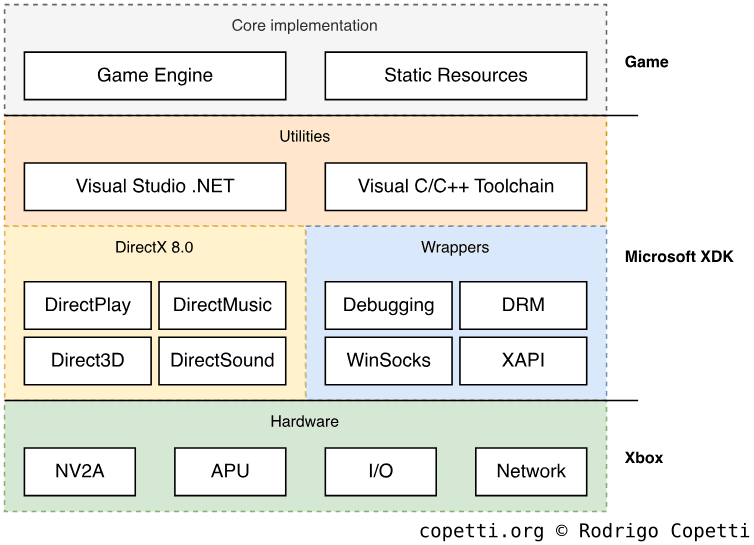

Microsoft XDK

Microsoft’s Xbox Development Kit or ‘XDK’ is the official SDK used for Xbox development. It’s a package that contains many tools, libraries and compilers. Most notably, it’s used alongside Visual Studio .NET (2002 version) which was quite an IDE from that time, for better or worse.

The graphics library is a customised implementation of Direct3D 8.0, which was extended to include Xbox-specific features. Direct3D was a very powerful API used to develop code compatible with many GPUs. With this, PC developers have the opportunity to port their PC games without too many changes (in theory!). Although, the syntax used for vertex programs and pixel shaders resembles downright assembly.

Apart from that, audio functionality is provided by DirectSound which takes care of the APU without the need to worry about moving audio data around. There are some network libraries as well, which are very convenient for achieving online functionality (i.e. multiplayer). The network API relies on Windows Sockets, which was Microsoft’s attempt to simplify network communications using a Windows-only protocol (albeit having a design based on its standardised counterpart, BSD sockets).

To try all of this out, Microsoft distributed their own development kit hardware which is just a retail unit tinted in green with double the RAM installed (128 MiB in total) and, sometimes, a different MCPX chip (called MCPX-2, which directly boots from the Flash ROM). It contains an enhanced version of the dashboard which launches executables signed by the XDK. On the other end, the Xbox Neighbourhood (a Windows application) was used to link the dev kit with Visual Studio, enabling easy deployment and debugging. To experiment with Xbox Live, Microsoft provided sandboxed servers as well.

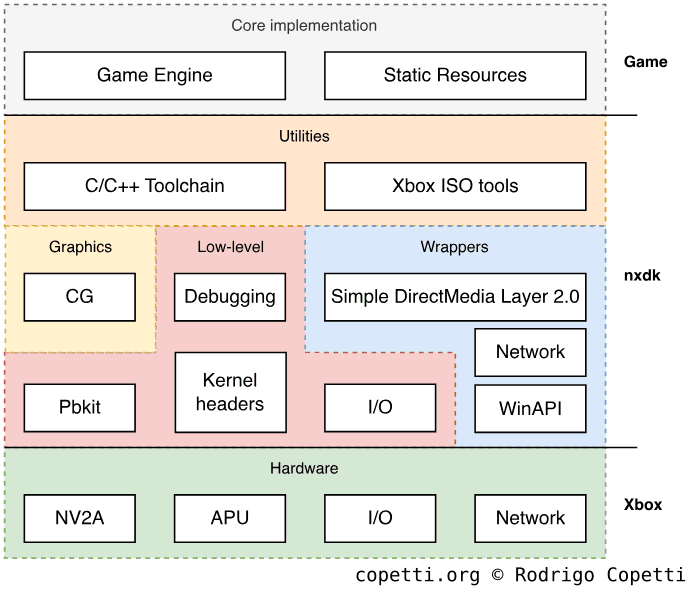

NXDK

To avoid Copyright litigation to Homebrew developers using the official SDK, a group of developers unaffiliated with Microsoft created a replacement of the official SDK called Open XDK. After some years, its development stopped, so another group picked it up from there and named the new fork New XDK or ‘nxdk’.

The ongoing project reverse-engineered the low-level hardware components (microcode, push-buffers, etc) and designed a new API in C/C++ which provides high-level calls to each portion of the system.

To simplify the graphics layer without relying on Direct3D, nxdk uses the CG compiler [26]. CG is a language created by Nvidia for developing shaders. CG is chained with other compilers to generate Xbox-compatible code. During compilation, CG code is converted into NV20-compatible assembly, then, this is translated again using a custom compiler to generate NV2A-compatible microcode and pushbuffer. For those who don’t want to use CG, nxdk also exposes the rest of the compilers to write low-level shaders.

The rest of the APIs available handle other services (audio, networking, etc). All in all, this library gives more control of the hardware (as opposed to the official SDK) at the exchange of not using Microsoft’s APIs (the de-facto standard, albeit completely proprietary). However, nxdk remains the most adequate option for developing legal Homebrew programs.

Medium

Games are distributed on dual-layer DVD discs (with up to 8.5 GB!), and they are subsequently read by a customised DVD drive that includes anti-piracy protections (despite using a standard interface, ATA). It’s worth mentioning that the XDK included some tools to customise the layout of data in the disc, enabling programmers to improve read speeds!

Now, the console also includes an internal 8 GB HDD, games use it to store saves or cache temporary content. The system, on the other hand, stores the dashboard, Xbox Live settings and network settings.

Network service

Forget about modems or experimental services. The Xbox included everything that nowadays we take for granted to provide a decent online service: Ethernet connection and a centralised online infrastructure (called Xbox Live).

Furthermore, not only Xbox Live enabled online multiplayer but it also included other features like audio streaming for real-time voice chat.

But what exactly is Xbox Live? Well, it’s just a collection of interconnected online services that companies can use to build their online platform. For instance, one of the services provides user profiles, so studios can use it as an authentication method when accessing the online functionalities of a game. In the official SDK, Microsoft includes some APIs to talk with the Xbox Live servers.

It’s important to point out that Microsoft controls whom to grant Xbox Live access to, so developers will have to register with Microsoft to obtain the authentication keys that will be used by their games.

The real online experience happens in the Title Server, which is the type of server that answers to clients (Xbox consoles) around the world and handles real-time communication. Microsoft included in their SDK some samples to show how to build these servers, although they relied on Windows systems and were meant to be deployed in data centres running Windows Server.

The start of a new trend

After analysing Microsoft’s implementation of Xbox Live and looking at the impact it had on the industry. It now sounds pretty obvious, right? As if the recipe for ‘proper online gaming’ (a.k.a Ethernet + Infrastructure) was always there, but not every company wanted to invest in it.

It turns out it’s not that simple: Microsoft also had to convince users they ‘needed’ this functionality, that online multiplayer wasn’t just an optional addition, but a fundamental part of some games. Otherwise, Microsoft’s efforts would just account for another ‘online attempt’.

Try imagining a world where no console gamer wanted online games, and where nobody believed a PC architecture could be a console. That was really how it was. Now it seems obvious BUT IT WASN’T.

– Seamus Blackley

Anti-Piracy and Homebrew

Independently whether this console contains off-the-shelf components or not, there’s a fair amount of security measures implemented.

Please note that RSA encryption is a recurring topic here, I previously introduced it in the Wii article, so if you are not familiar with RSA or any other symmetric/asymmetric encryption systems please take a look at that article first.

That being said, let’s take a look.

DVD copy protection

Game discs are protected both logically and physically to prevent unauthorised duplication (this shouldn’t be a surprise by now).

On the logical side, game discs include a couple of ‘traps’ to trick conventional DVD readers so they can’t find the actual game content. For instance, the first area of the disc is formatted like a conventional DVD, and inside that section, there’s a warning message that plays if it’s inserted in a non-Xbox system. In reality, game data is found on a second partition, but the metadata required to find that partition is not encoded in a format conventional DVD readers expect, so only a specialised reader (hence the Xbox’s) will find the game.

On the physical side, I’m afraid that at this time, it’s not publicly known yet what data the driver and the disc exchange to perform validation. The disc contains an inaccessible inner ring (by conventional readers) that stores unique identifiers, but it’s not known how this data is used.

System protection

Let us go over the rest of the security measures that this system originally implemented.

Introduction

The Flash ROM and EEPROM containing the ‘BIOS’ and sensible data, respectively, are encrypted using a RC-4 key. After the Kernel is booted from the BIOS, it will only launch executables signed by Microsoft using RSA encryption.

The HDD, on the other side, is formatted with a completely proprietary and undocumented filesystem called FATX.

This was a brief introduction to the chain of trust that Microsoft implemented. Seems pretty simple right? Well, something’s odd: The execution is controlled by the CPU, but this is an off-the-shelf chip, so how does it understand data encrypted with RC-4? The answer is that it doesn’t, so somewhere in this console is an unencrypted piece of code that sets up the first stage of encryption. This code, in particular, was the target for most hackers who strived to crack this console after it launched.

Bootstrap search

Since it’s officially documented by Intel that their processors will start execution at address 0xFFFF.FFF0, hackers focused on searching for that code in the Flash ROM (which in turn will lead to the RC-4 key). This is what a popular hacker and researcher named Andrew ‘bunnie’ Huang attempted during his academic research. The findings were quite interesting: The upper 512 bytes of the Flash ROM contains security routines including the key, but it doesn’t work for the retail system [27]. I speculate that Microsoft may have left that code from prototype/debug units (possibly accidental, since this block exposes the algorithms that Microsoft applied). In conclusion, this was considered garbage code so bunnie realised the real 0xFFFF.FFF0 wasn’t in the Flash ROM.

To make a long story short, 0xFFFF.FFF0 was hidden in the MCPX chip: It contained a hidden 512 B ROM that would be executed once and hidden afterwards. This ROM was not easy to extract, so bunnie resorted to tapping the HyperTransport bus to catch the RC-4 key once it was transmitted.

And so it happened, bunnie published the key as part of his research and Microsoft was not happy about this. Thus, the hacking community found a way to gain control of the first security layer of this console, which included the Kernel.

Permanent unlock

Cracking the RSA layer was never meant to be easy, but since hackers gained access to the Kernel, it would now be possible to reverse engineer it and develop patches that could nullify RSA altogether. Lo and behold, this eventually happened and opened the door to the Homebrew community. Anyone could now develop programs that could be executed on a modified Xbox without the approval of Microsoft. Some groups developed replacements for the original Dashboard which could do more functions, such as executing Linux!

This, however, required users to modify their BIOS using specialised hardware, which not everyone could do. In later years, new exploits were discovered that could easily bootstrap the main hack, one of them consisted of inserting a forged save-game of ‘007: Agent Under Fire’ or ‘Splinter Cell’ that would generate a buffer overflow to kickstart a homebrew tool that could install a permanent exploit in the hard disk. The ‘permanent exploit’ was possible because the original Dashboard was subject to yet another buffer overflow using a forged font file [28] (note that fonts didn’t need to be signed).

Modchips

From the piracy side of things, Modchips also appeared: Instead of tampering with the DVD drive, modchips overlapped the Flash ROM by exploiting the fact that the MCPX ROM could boot a secondary BIOS if it was found on an unused LPC port.

The substitute BIOS contained patched routines that could enable reading any type of game disc (especially the conventional ones).

The response

Microsoft released many hardware revisions reducing the amount of exposure in their electronics and saving up costs. Meanwhile, software updates were released that updated both the Kernel and the Dashboard in an effort to reduce the number of vulnerabilities. However, some game exploits still managed to persist and what remained was another ‘cat-and-mouse’ game.

Another point to mention is that Xbox Live was itself an effective prevention mechanism against piracy. Microsoft was able to block Xbox Live to those consoles with unauthorised modifications, which was a trade-off that typical users had to consider before hacking their consoles with the only goal of playing pirated copies.

That’s all folks

After a couple of months with deadlines and exams in the middle, the next article has finally been finished. I admit this one continues the trend of adding too much information and trivia, but while this research started with small (and frustrating) steps, I’m glad I found a lot of support from one special community, XboxDev, that helped me gather lots of information.

For anyone who would like to know more about this console, XboxDev is actively working on nxdk (along with different emulators) which strives to do things that were previously considered impossible in Xbox homebrew, so I suggest visiting their community for more information.

From my side, I’m going to take a few days to think carefully about the next article (and potentially go back a couple of generations to analyse a console I forgot about).

Until next time!

Rodrigo