Supporting imagery

Model

Released on 22/11/2005 in America, 02/12/2005 in Europe and 10/12/2005 in Japan

Released on 18/06/2010 in America, 24/06/2010 in Japan and 16/07/2010 in Europe

Released on 10/06/2013 in America, 20/06/2013 in Europe and similar in Japan

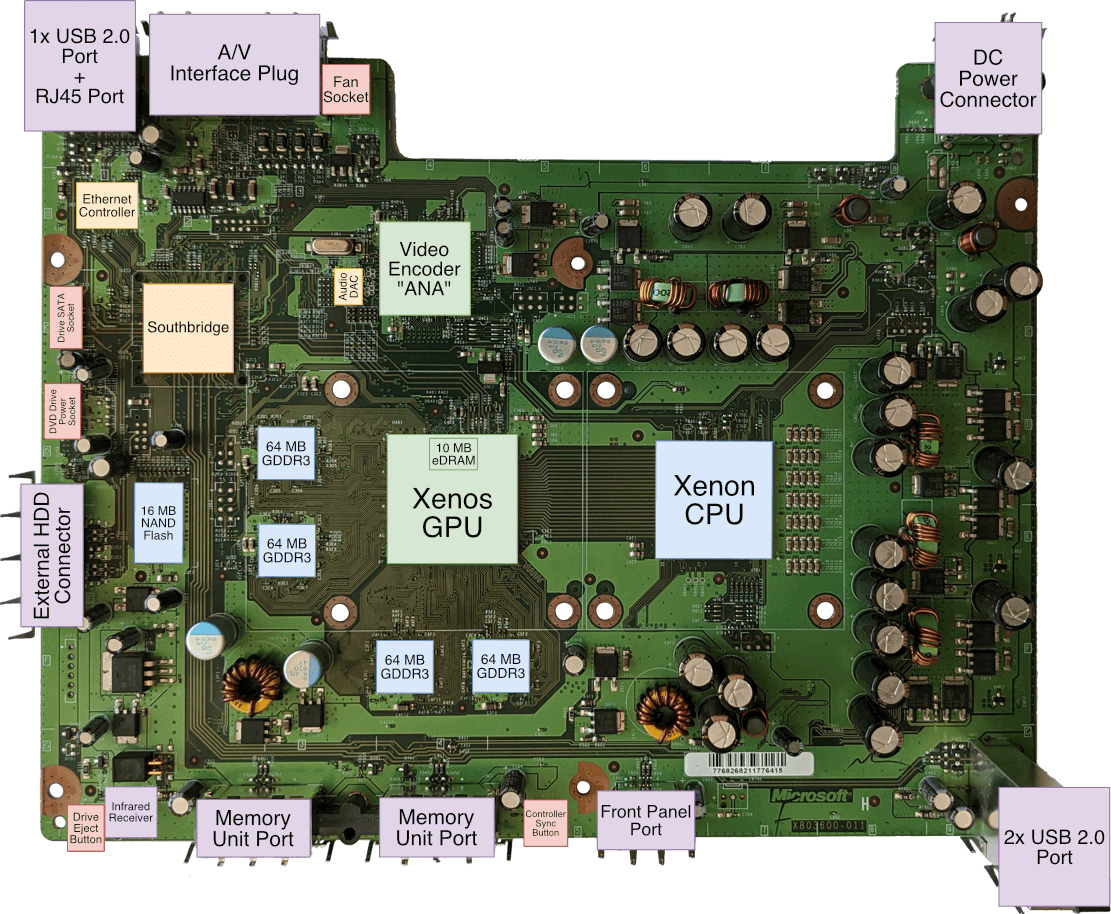

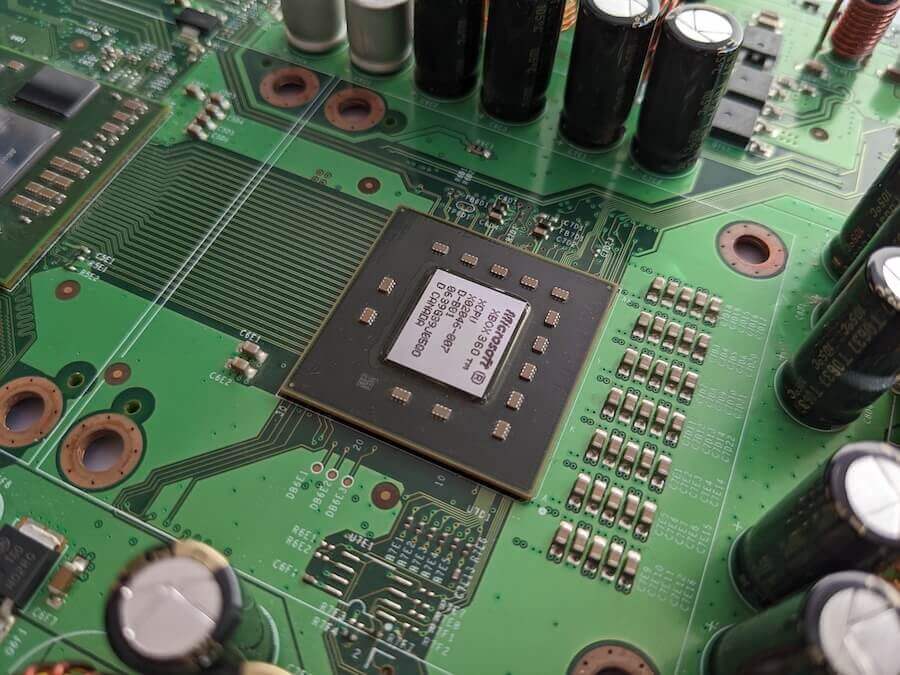

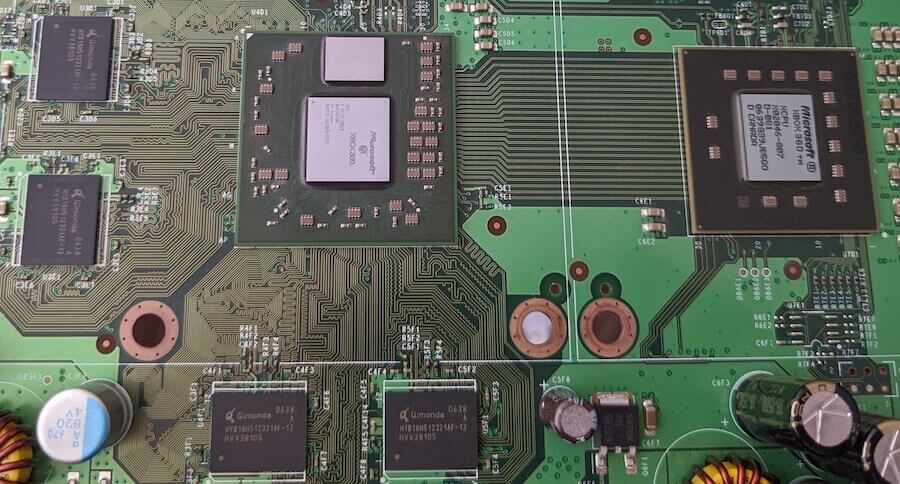

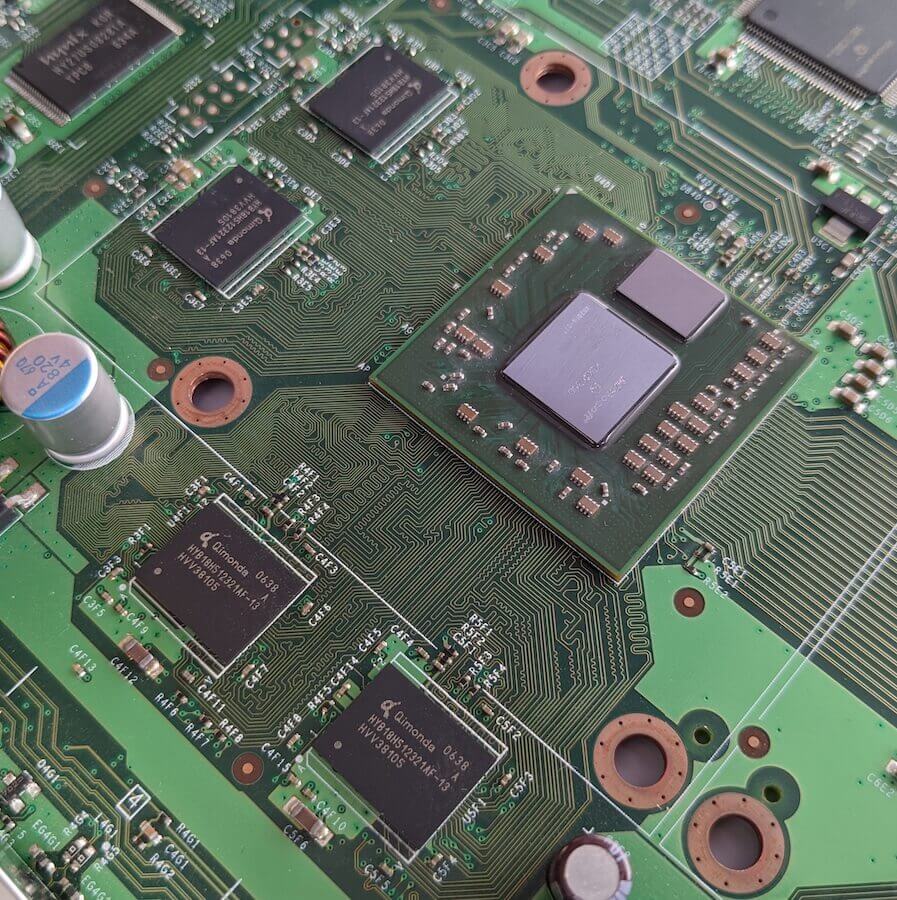

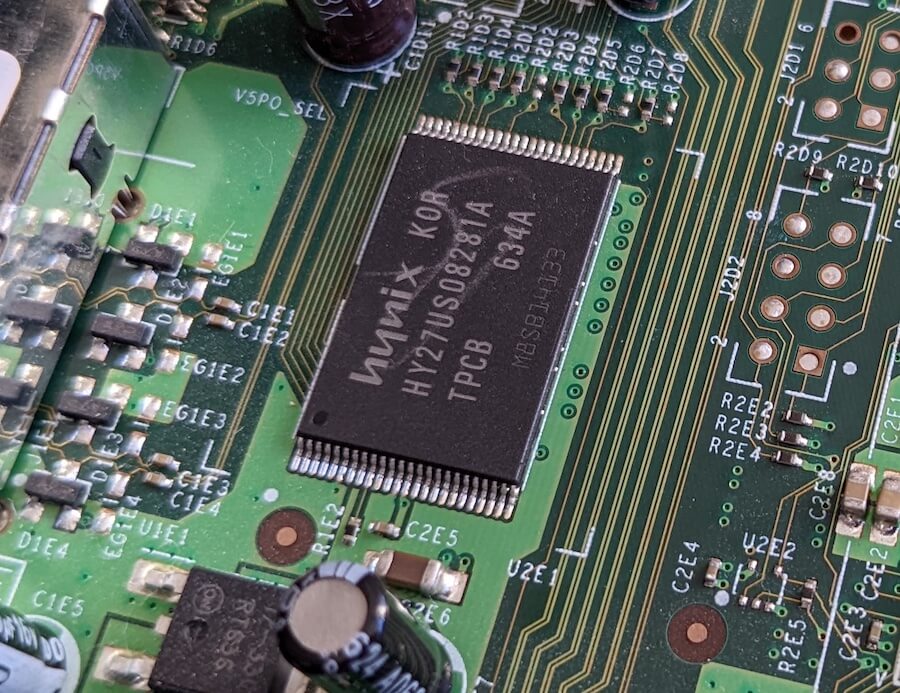

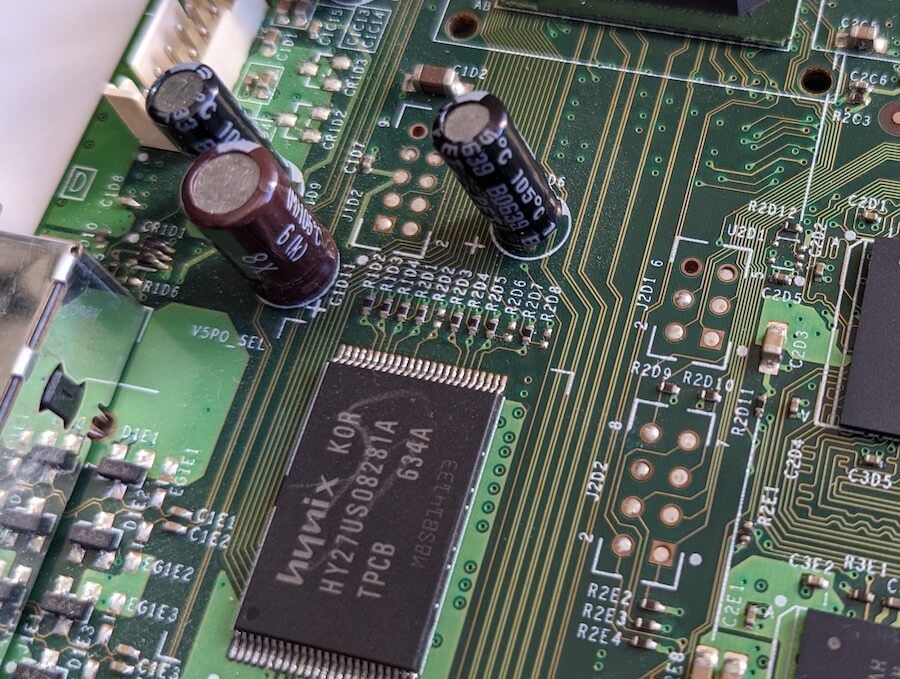

Motherboard

Showing the 'Xenon' revision (the first one), taken from my model from 2005. Xenon motherboards are also famous for being defective by design (they get too hot to play games with!). Remaining GDDR3 chips are found on the back.

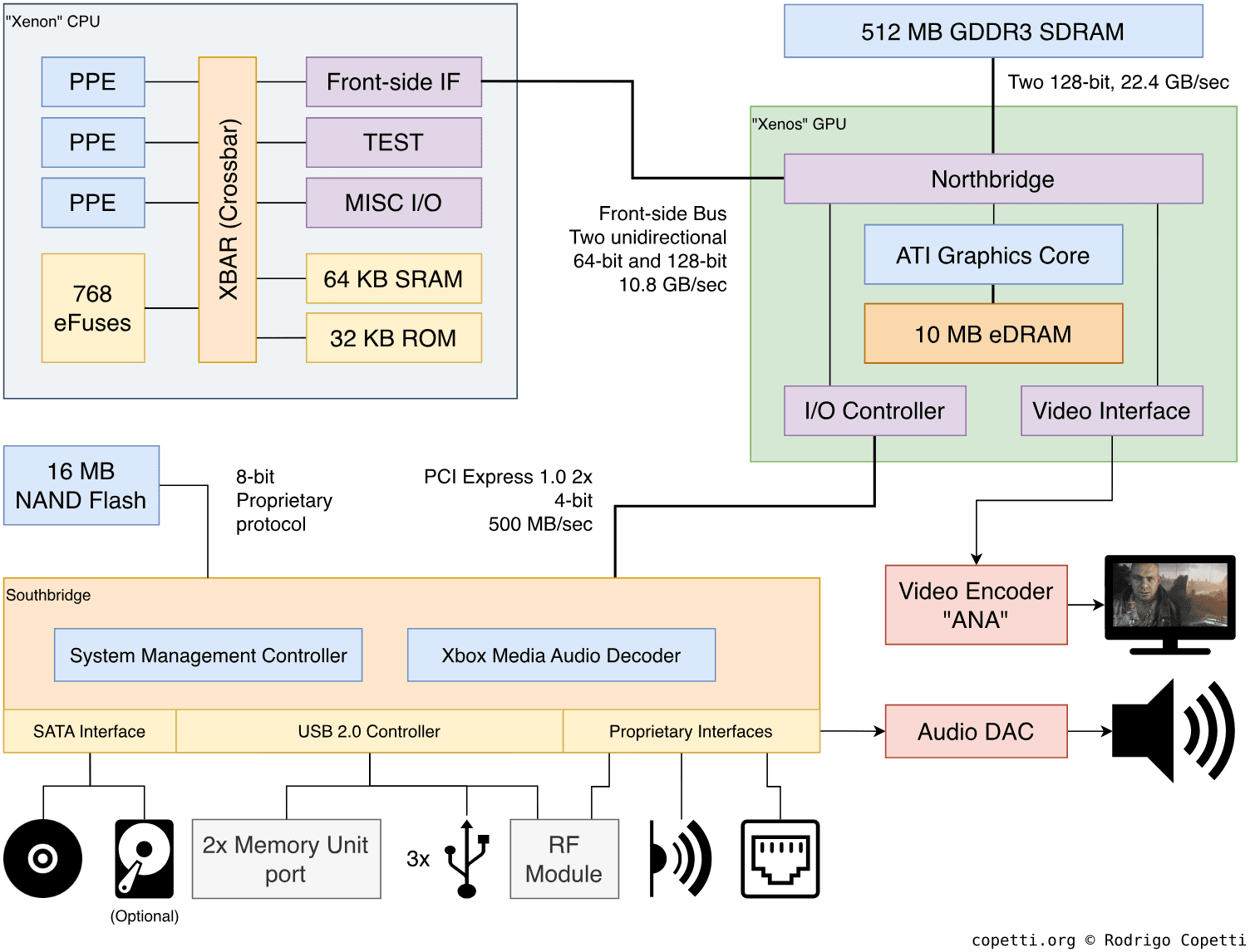

Diagram

A quick introduction

Released a year before its main competitor, the Xbox 360 was already claiming technological superiority over the yet-to-be-seen PlayStation 3. But while the Xbox 360 might be the flagship of the 7th generation, it will need to fight strongly once Nintendo and Sony take up retail space.

This new entry in the console architecture series will give you an additional perspective on how technology was envisioned during the early naughties, with emphasis on the emerging ‘multi-core’ processor and unorthodox symbiosis between components, all of which enabled engineers to tackle unsolvable challenges with cost-effective solutions.

Highly recommended pre-reading

The first section of this writing (titled ‘CPU’) makes recurring references to IBM and Sony’s joint venture, Cell. If you don’t know about that component, I highly suggest that you read my previous article about the PS3 beforehand, the latter is written as if the Xbox 360 never existed. This was intentional to avoid confusing the reader with circular references. Hence, the new article completes the timeline by adding Xbox 360 into the mix.

For those who are already familiar with the PS3’s architecture, I’ve structured this study similar to the PS3 article, so you’ll be able to compare both side-by-side objectively if you choose to do so.

Personal video introduction

Because this article is way longer than my previous ones, I also made a quick video where I (attempt to) present this article and give you an idea of the content you will find. You can watch it here. It’s my first ‘personal introduction’, so you’ll have to forgive my occasional fillers!

CPU

Once again, we find ourselves with a new type of CPU that is unlike anything seen on the store shelves. After all, this is another 7th-generation console that reflects an obsessive need for innovation, a peculiar trait during that era.

Introduction

Before we discuss the architecture, I’ll start with a bit of history to bring you up-to-speed. The following paragraphs focus on the business aspect of the Xbox 360’s CPU, whose sequence of events you may find amusing, to say the least.

I’ll try to keep it short so we can focus on the main topics of this series, but if in the end, you are interested in more, you may enjoy a book called ‘The Race For A New Game Machine’ which is written by the former executives at IBM.

From complier to ruler

After enjoying the surprising success of the original Xbox, it was time for Microsoft to work on the successor. The company started by looking for vendors that could face off against Sony’s upcoming technology, however, unlike their previous development, Microsoft now enjoyed the upper hand in forthcoming negotiations.

To put things in context, back when the original Xbox project was still at an early stage, neither Intel nor Nvidia were willing to share their intellectual property with Microsoft. This decision limited Microsoft’s capacity to mould Nvidia’s or Intel’s chips for the specific needs of the Xbox.

For instance, the security subsystem that protected the console against the execution of unauthorised code was implemented outside these two critical chips. This made it vulnerable to snooping attacks that eventually paved way for the execution of Homebrew and piracy. Moreover, Microsoft did not control the manufacturing stage either, so the production of Xbox systems was at the mercy of Intel’s and Nvidia’s supply.

Well, now that Microsoft had gained more leverage in the console market, they weren’t willing to give away those rights anymore.

Sharing common problems

As with any other company in the computer business, the innovation crisis of the early noughties affected both Microsoft and Sony indiscriminately. The difference, however, was that the two placed their bets on different designs for their CPUs. The original Xbox relied on popular off-the-shelf stock (Intel’s Pentium III) with slight customisations, this was a single-core CPU extended with vectorised instructions and a sophisticated cache design. On the other side, Sony’s vectorised venture (the Emotion Engine) consisted of a low-end CPU surrounded by proprietary but potent assistants.

For their new generation, Microsoft settled for a conservative design combined with some experimental ideas. According to their checklist, the new CPU would be multi-core (that is, a chip housing many CPU cores in a symmetrical and homogeneous layout) and the supplier would have to share their Intellectual Property (IP) with Microsoft [2].

The last condition was as critical as the first, as it would enable the Xbox team to bundle a security system inside the chip (which, unlike the original Xbox, would be properly shielded). Furthermore, the IP rights would grant Microsoft a choice of third-party manufacturers to handle demand and negotiate better costs, resulting in a new console with competitive pricing.

Thus, Microsoft began meeting with Intel, though the talks didn’t last long, as Intel wasn’t willing to give out its secret recipe. So, Microsoft kept looking.

Resentful old friends

It so happened that one of the potential candidates for Microsoft was none other than IBM. Maybe I watched too many dramatic documentaries, but I always pictured the two as the kind of passive-aggressive ‘friends’ who only smile at each other if they are among other people.

You see, in the past, IBM and Microsoft formed many partnerships that ended up with bitterness between the two. Be as it may, their agreements ended up disrupting the status quo of the global market and paved the way for new types of consumer products and developments. To name a few examples:

- The arrival of the IBM Personal Computer in 1981 led to a new market of ‘personal computers’ and the subsequent choice of Microsoft’s ‘MS-DOS’ as the default operating system. This granted Microsoft a monopolistic dominance in the PC business in the years to come.

- In the 90s, with the advent of home networking and affordable servers and workstations, IBM and Microsoft’s new venture resulted in OS/2, a new operating system targeting high-end IBM computers. However, upon the unexpected release of Microsoft’s Windows NT, IBM was left alone to fight in an arena already favouring Windows.

By the turn of the century, IBM returned its attention to in-house products, including a partnership with Apple and Motorola that resulted in a series of CPUs with a unique architecture called PowerPC.

When Microsoft approached IBM for a new frictionless venture, IBM was already working with Toshiba and Sony to create a superior PowerPC processor for scientific applications. Nevertheless, IBM was open to new business opportunities.

The new CPU partner

In a turn of events, IBM agreed to share its IP and to design a new multi-core processor, and so the Xbox 360’s CPU supplier became IBM. Although, you may remember this was the same IBM that already signed an agreement with Sony and Toshiba to produce the PlayStation’s 3 CPU (‘Cell’). Apparently, IBM assumed Microsoft was not aware of the Cell project [3], and their current contract with Sony did not forbid them from selling to third parties.

All three companies [IBM, Toshiba and Sony]… legally all had rights to go and put any of that technology, any of those processor cores into other spaces. (…) It is very common to develop an interesting, leading-edge new technology and then utilize that technology across multiple platforms. (…) I guess what everyone didn’t anticipate was – before we even got done with the Cell chip and PS3 product – that we’d be showing this off specifically to a competitor. [4]

– David Shippy, chief architect of the Power Processing Unit (PPU)

Ironically, as of 2022, IBM’s PowerPC chips have vanished from both desktop computers and video consoles, maybe this set a bad precedent and greatly affected IBM’s trust in future businesses? I go over this effect later on.

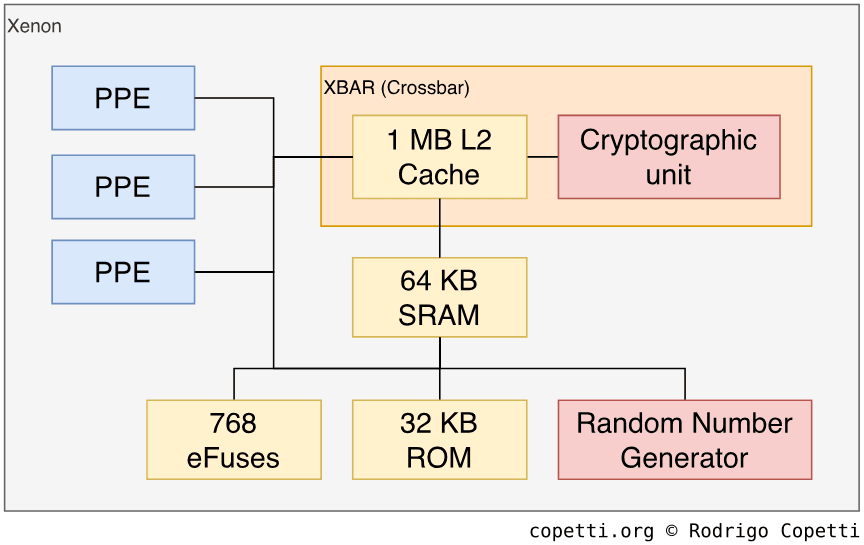

To sum it up, IBM signed an agreement with Sony and Toshiba to develop Cell in 2001. Two years later, in 2003, IBM agreed to supply Microsoft with a new low-powered multi-core CPU. Microsoft’s CPU will be called Xenon and will inherit part of Cell’s technology, with extra input from Microsoft (focusing on multi-core homogeneous computing and bespoke security). Also, while IBM would brand Cell with its ‘BladeCenter’ line of servers, Xenon could only be fitted on an Xbox 360 motherboard.

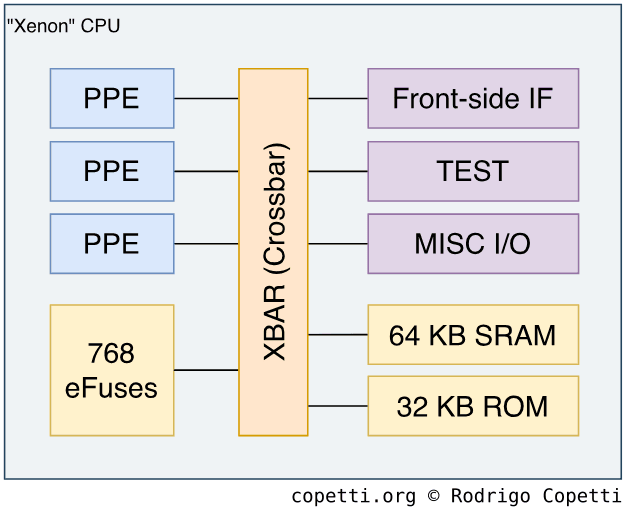

Cell’s half-sibling

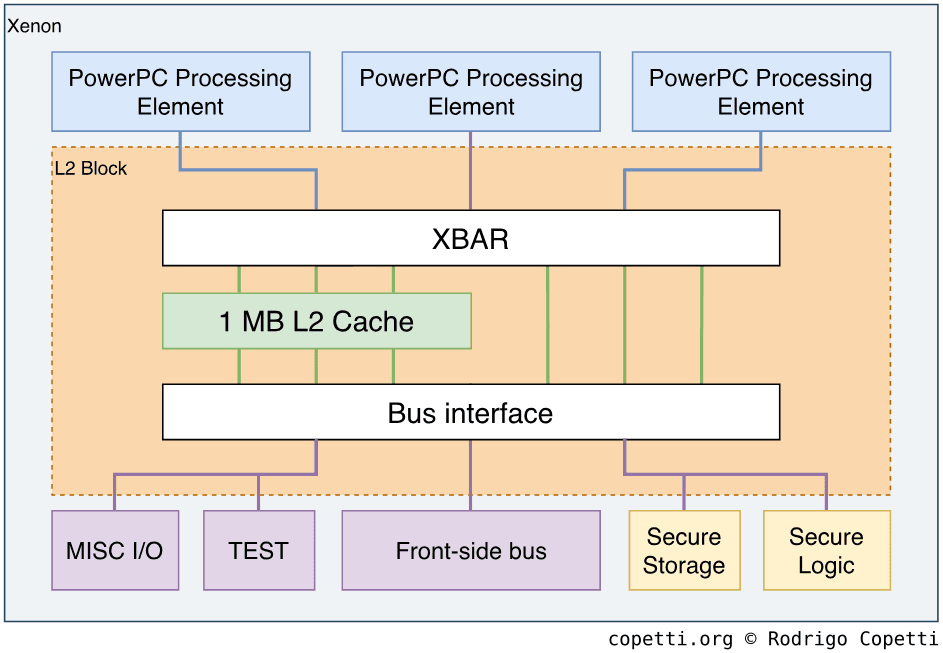

Now that we’ve positioned Microsoft and IBM on the map, let’s talk about the new CPU. This is how Xenon materialised at the end of the Xbox 360 project…

Don’t worry, all of these components will be explained throughout this article, starting with the ‘PPE’ blocks shown at the top left corner.

A new look at CPU history

The Cell project, with its obsession with vectorised computations, introduced very interesting proposals to radically tackle the ongoing constraints that hindered technological progress. These constraints, however, are very complex. So it wouldn’t be fair to say that Cell’s methods were the only -or even best- solution. In other words, by studying Xenon’s architecture (which competed side-by-side with Cell’s) we can gain a different perspective on how CPU architecture evolved throughout that era (the early 00s) and subsequently influenced the next decade of CPUs.

In doing so, you’ll perceive that Xenon takes a more conservative approach than Cell. If we take another look at the previous diagram of Xenon, you can notice that the latter is equipped with the famous PowerPC Processing Elements (PPEs), which is also the most important piece of Cell. However, Xenon’s is now equipped with three of them. Additionally, the Synergic Processors Units (SPUs) are no more.

After all, Microsoft didn’t want processors of very different natures squashed in their CPU. They instructed IBM to compose three powerful cores and enhance them with the ingredients game developers would expect to find. With this approach, IBM and Microsoft were also able to add non-standard features without disrupting the traditional modus operandi of developers.

Truth to be told, this also resulted in aggressive budget cuts to keep this design (and the rest of the system) at a competitive price range. To put it in context, multi-core CPUs for PCs weren’t on the store shelves while IBM was building Xenon, and when they debuted in 2005 (coincidentally, the same year the Xbox 360 reached the stores), AMD priced their cheapest Athlon X2 at $537 (equivalent to ~£452 in 2021 money) and Intel charged $241 (equivalent to ~£203 in 2021 money) for their low-end Pentium D [5] - and let’s not forget the box only included the CPU.

How this study is organised

We’ll now take a look main components that comprise Sony’s counterpart. To avoid repeating existing information, I’ll focus on the novelties of Xenon.

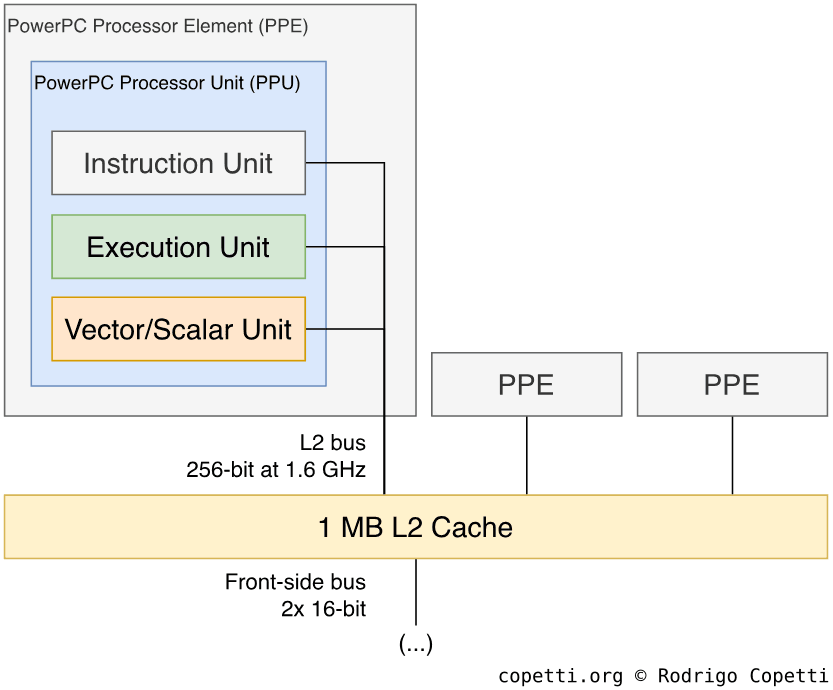

Having said that, the new CPU runs at 3.2 GHz and it includes so much circuitry that, for this study, we have to split it into different groups:

- The three leaders that execute the program’s instructions. At first, each resembles Cell’s PowerPC Processing Element (PPE), but you’ll soon see that they are actually a superset of it. Additionally, since we’ve got three of them now, it may seem as if the whole chip behaves like a Ceberus monster, where each core may claim control of the whole system. Alas, that’s not feasible in a computer, so the first core is the designated master core while the others will be taking assistant roles.

- A single interface that interconnects the cores with the rest of the system. This bus is called XBAR (pronounced ‘Crossbar’).

- Like in Cell, there are other proprietary interfaces used for debugging or maintenance (i.e. temperature) but these will not be mentioned until we reach the ‘Anti-piracy’ section.

- The security block which Microsoft oversaw to implement the anti-piracy system. It’s a very complex section, so to avoid overwhelming you with information, I’ll explain it in the ‘Anti-piracy’ section as well.

The different approach for Xenon

To explain the aforementioned groups, I’ve organised the study of Xenon into these areas, in that order:

- The bus connecting all the cores, the XBAR and its special L2 cache block.

- The new refinements of the PowerPC Processing Element (PPE).

- The unusual abundance of general-purpose memory.

- The new programming model suggested (and, in some ways, enforced) by Microsoft.

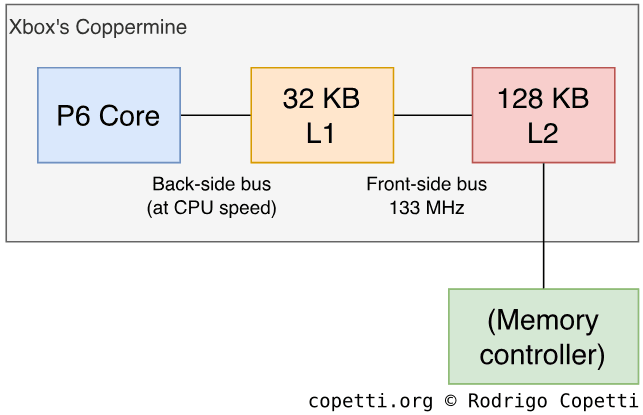

Inside Xenon: The messenger

The original chip (Cell) was required to house twelve independent nodes actively moving data around, this forced IBM engineers to devise a complicated system that could tackle emerging bottlenecks, which materialised in the form of the Element Interconnect Bus (EIB). With the Xbox 360, Xenon only accommodates three units (the three PPEs), so the EIB has no purpose here. Thus, a simpler solution called XBAR was produced to focus solely on the three PPEs, with space for extra functionality.

XBAR relies on a mesh topology that doesn’t direct traffic in a token-style manner. Instead, each node is provided with a dedicated lane to move its data through [6]. This may appear more optimal than the token topology of the EIB, but that’s because the XBAR only needs to serve a small number of nodes. Furthermore, the XBAR operates at full speed (3.2 GHz).

To be fair, until now I only talked about the particular interface that interconnects the PPEs. Well, the XBAR is just one piece of the sizeable chunk IBM designed for Xenon. It turns out the leftover space gave them room to incorporate another very important block that speeds up the transactions between the PPEs and the rest of the system: L2 Cache.

Shared cache

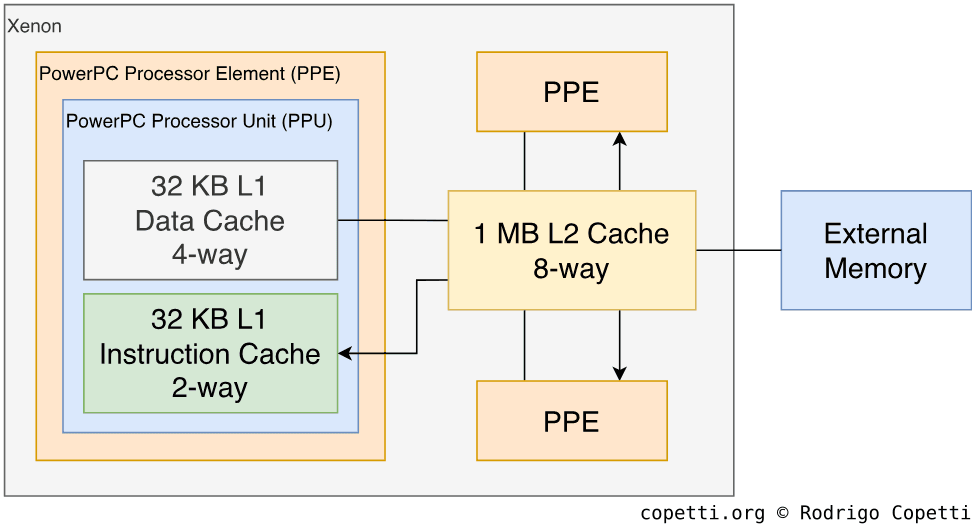

Once the PPEs pass through the XBAR, they get access to 1 MB worth of L2 cache. The L2 block is also connected in a meshed manner, where each PPE gets a separate 256-bit bus but is now clocked at 1.6 GHz (half the PPEs’ speed) [7].

Coincidentally, Cell also houses 512 KB of L2 cache for its single PPE. I only described it in one sentence in my previous article. Now, however, we find ourselves with a larger space that’s also shared between three cores, so I find it necessary to dive into the properties of the L2 block so we can understand how it will condition the performance of the PPEs.

First things first, every time the cache fetches data from memory (in the event of a ‘cache miss’), it does so by pulling a large slice called ‘cache line’, which is 128 Bytes wide in the case of Cell and Xenon. Then, L2 records the cache line on an internal list for locating it in the future. Moreover, in Xenon/Cell, L2 is 8-way associative, which means that cache sets may store up to eight different cache lines. Don’t worry if you don’t know what this means, the theory behind CPU cache can be hard to follow, especially if you only want to learn about game consoles. In layman’s terms, the greater the number of associations, the fewer probabilities of cache misses, but the slower it becomes to iterate through the internal list.

The choice of an 8-way associative cache was not a rash decision for Xenon, as providing eight associations can alleviate the six simultaneous threads (each PPE is dual-threaded) trying to access the L2 block at the same time. This also balances frequent cache misses and lookup times. All of this, while keeping the costs down. For comparison purposes, the expensive Intel ‘Smithfield’ (a Pentium D from 2005) provides two cores with 2 MB of L2 cache each! [8]

It wouldn’t be the first time Microsoft trimmed the cache for pricing purposes, so it will be up to developers to optimise its usage. To assist with this, XBAR bundles additional logic like ‘cache locking’ which will be further explained in the ‘Graphics’ section.

Inside Xenon: The leader(s)

This is as far as we go with our description of the XBAR and L2 cache, let’s now talk about the actual CPU. Just a reminder that, since I’ve already dissected the standard PPE (found in Cell) for the PS3 article, I’ll be focusing on the novelties here.

To start with, Xenon’s PPEs don’t feature a PowerPC Processor Storage Subsystem (PPSS) anymore, presumably since the interfacing part is handled by the XBAR and the L2 cache is now shared across the three units.

To be honest, I’m not sure why technical manuals keep calling Xenon’s PPEs a ‘PPE’ as they better resemble a PPU.

Anyway, let’s go over the significant changes that Microsoft liked to brag about when being compared with the PlayStation 3.

The new vector units

As the Synergistic Processor Elements (SPEs) were Sony’s secret weapon and Microsoft was only interested in homogeneous systems, IBM presented an alternative approach to speed up the manipulation of vectors and matrices in Xenon [9]. In a nutshell, IBM boosted the VMX unit (the SIMD block found within the PPEs) which evolved into VMX128, now housing more registers and opcodes.

The initial VMX specification implemented in the PlayStation 3 provides 32 128-bit registers and instructions for operating up to three 32-bit scalars. This worked to an acceptable degree with general-purpose applications that depend on SIMD operations, although the real performance would be unlocked once the SPEs are added into the equation. By contrast, Microsoft wanted programmers to port SIMD-hungry applications without extra hassle, and the new VMX128 unit reflects that.

VMX128 supplies 128 128-bit registers instead, along with an adapted instruction set to manipulate the larger set of registers. To accomplish that, IBM changed the opcode format to allocate 7 bits (as opposed to 5 bits) for referencing its extended register file [10]. This is possible thanks to some trickery applied on the last five bits at the end of the 32-bit opcode [11]. The last five bits are mostly, but not completely, unused by VMX. Consequently, VMX128 is incompatible with a subset of VMX instructions (related to integer multiplication and additions).

Furthermore, VMX128 adds new instructions that compute the dot product of two vectors composed of up to three 32-bit floating-point numbers; and others that handle Direct3D’s data compression formats [12] (it’s worth mentioning that DirectX is the sole API for programming this console). Finally, thanks to the symmetric design of Xenon and its multi-threaded model (dual-issuing), VMX128’s register file is duplicated, so there are 256 128-bit registers per core!

As we reach the end of this section, there’s still one question left unanswered: which is faster for vector operations, 1 VMX + 6 SPEs (as in the PS3) or 3 VMX128 units (as in the Xbox 360)? Well, their designs are too divergent, so it’s hard to quantify. One could say ‘The SPE can execute up to two instructions per cycle while Xenon takes 12 cycles to add two vectors (due to the long pipeline of the PPE)’ but that’s relative, as the SPE’s memory scope is restricted to its local memory (requiring DMA calls to interact with the outside), while Xenon’s PPEs can access any memory location. So, in conclusion, these are two contrasting models and programmers will just have to get the best out of them.

A new but short-lived instruction

With the advent of a larger cache system, Microsoft and IBM extended the PowerPC instruction set to accommodate some instructions that operate these blocks from the program side, in case programmers wish to make manual interventions (such as caching data ahead of time or saving L2 space). In any case, the standard PowerPC specification already provides the dcbt (‘Data Cache Block Touch’) instruction to fetch data from memory into the L1 cache (individual for each core) [13]. Nonetheless, Microsoft took a step forward and added xdcbt (‘Extended Data Cache Block Touch’) to fill the L1 cache without even going through L2 (shared across all cores) [14]. This makes sense as the shared L2 is a new addition of Xenon. However, bypassing L2 is a risky operation as two cores may end up seeing different data (cache incoherency), so it will require correct handling from the program side to keep cache incoherency and race conditions out of the way.

As luck would have it, xdcbt worked fine until Microsoft started receiving error reports from game studios [15]. Initially, Microsoft relied on this instruction for common routines available through their API (such as memcpy()) but they didn’t account for the consequent lack of cache coherence. Thus, uses of xdcbt were subsequently removed from their APIs. Yet, studios found a bigger problem: branching instructions followed up by xdcbt always execute the latter. It turns out the branch predictor will attempt to execute xdcbt (as any other instruction that may be undone later on, if the prediction turns out to be incorrect) with the exception that once the cache blocks are mangled, there’s no way to undo it (becoming a hazard). Thus, the program will not synchronise the caches as it assumes xdcbt hasn’t been triggered, leaving the PPEs in a disarrayed state.

In the end, Microsoft purged xdcbt from the compiler due to its non-deterministic (thus unpredictable) behaviour, and what’s left of it is just an anecdote.

Revisiting old paradigms

There’s a recurring subject found in noteworthy writings from 2005 like ‘Inside the Xbox 360’ by Jon Stokes [16] or ‘Understanding the Cell Microprocessor’ by Anand Lal Shimpi [17], and that is the lack of out-of-order execution that once debuted in early PowerPC chips like Gekko, but for some reason is completely absent in Cell & Xenon. If you recall from the GameCube article (which I wrote two years ago), Gekko is an out-of-order CPU, meaning it’s able to analyse the instruction stream as instructions come in, and subsequently reorder them to better distribute the load on Gekko’s internal units.

By then, CPU cores employing out-of-order execution were in the order of the day (pun intended). IBM’s PowerPC 604 (1994) brought it to high-end Macintosh computers, Intel’s P6 (1995) introduced it to the x86 line and MIPS implemented it with the R10000 (1996) CPU, a successor of the R4000 (found on the Nintendo 64). Afterwards, all of a sudden, Cell and Xenon arrive with an in-order execution style… care to explain?

To understand this turn of events, let’s take a closer look at the Out-of-order execution (OoO) model. OoO is not a Lego piece that engineers fit and then move on to the next part. Pipelined CPUs are susceptible to a whole new range of hazards, which means that the slightest addition may lead to a complete redesign. For instance, OoO requires altering the register file to fit register renaming [18], a clever technique where the CPU houses more registers than the instruction set references, enabling the CPU to store multiple copies of the program state and prevent dependency problems that arise after altering the original order of the instructions. All in all, while these solutions are interesting, they add complexity to the CPU chip, and that can pose a threat to future scalability.

The PowerPC Processor Element (PPE) derives from POWER4 which is itself an OoO core. However, POWER4 is an independent (and power-hungry) chip by itself, while the PPE is either surrounded by 7 SPEs (as with the PlayStation 3/Cell) or by two more PPEs (as with the Xbox 360/Xenon). These changes take up space and the dimensions of the CPU chip are critical in terms of price and heat emission. So, in the end, I imagine IBM didn’t see enough advantages for applying OoO on an application-specific machine like the PS3 or Xbox 360.

An alternative solution

Look at it this way, why was OoO invented in the first place? To prevent the CPU from idling (as idling = wasted resources). So, will the applications (3D gaming) be prone to this issue? Maybe, but it’s also true that OoO is not the only possible solution to this problem! Introducing Thread level parallelism (TLP).

What if instead of sorting out which instructions should be executed first, we duplicate the resources into two (or more) groups called ‘threads’ and let the program switch between the different groups of resources (multi-threading) as it sees more fit. This is what IBM’s engineers went for, hence the reason the PPE is dual-issued. The new technique, called Thread level parallelism (TLP), differentiates itself from Instruction level parallelism (ILP) by letting the program, as opposed to the CPU, to come up with its own solution. With Xenon and Cell, it’s now left to the compiler and the program’s multi-threading implementation to produce an efficient sequence of instructions.

The interesting thing is that neither approach is better or worse, out-of-order processors are still found in the market (Intel/AMD still supports OoO along with an obscene amount of other techniques, while ARM adopted OoO with the Cortex-A9 in 2007). On top of that, those CPUs have multi-threaded cores and even bundle multiple cores within the same chip, so you get a mix of both techniques (TLP and ILP).

Eroded relationships

Conversely, whilst the omission of out-of-order may look justified from a engineering standpoint, this would ultimately wither trust in IBM’s long-term abilities. Apple, sensing that future PowerPC chips would no longer stand against Intel [19], was the first to abandon its partnership and switch to Intel in 2005 (just in time for Yonah). Nonetheless, this didn’t worry IBM, who preferred to focus on its server and gaming sector.

The long-term outcome of the PowerPC CPU, however, became extinction. The aforementioned technical constraints (after all, IBM used to be a trailblazer in out-of-order design), combined with questionable business ethics (the fact IBM secretly designed for two close rivals at once), resulted in the loss of the entire console market: Sony and Microsoft selected AMD CPUs for their next-generation console. A decade later, Nintendo’s Wii U would become the last console to bundle a PowerPC chip.

Inside Xenon: Main Memory

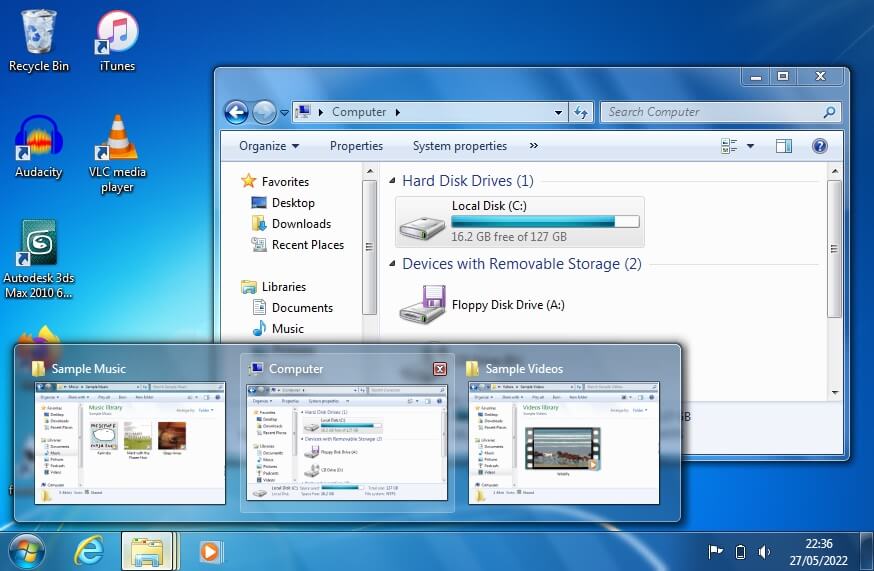

Unlike its competitor equipped with 256 MB of XDR DRAM, there’s 0 MB of external memory installed next to Xenon. That’s right, a 100% decrease compared to the Japanese counterpart.

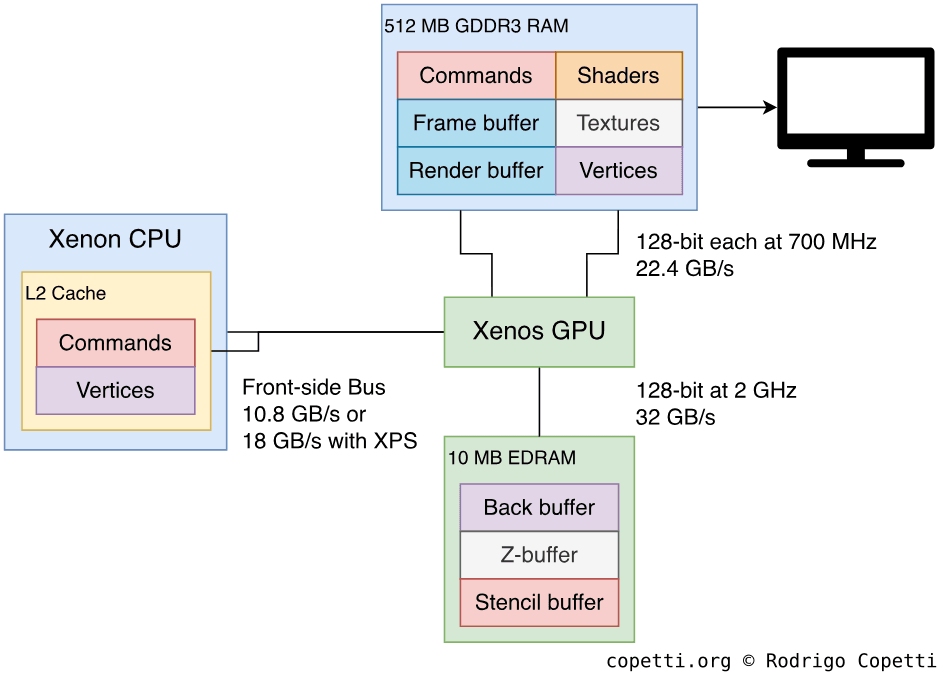

Okay… let me rephrase that. On the motherboard, multiple chips provide a total of 512 MB of GDDR3 SDRAM, but they are sitting next to the GPU, not the CPU. So… you probably guessed it. Just like the original Xbox, Microsoft went for the Unified Memory Architecture (UMA) layout, where all components share the same RAM chips. This provides more flexibility in the amount of memory reserved for the CPU or GPU. However, a single point of access for various components means the far away components (like the CPU) will suffer higher latency compared to the hypothetical case where the CPU was given dedicated memory. This was duly noted by IBM and Microsoft engineers and subsequently tackled with the aforementioned L2 cache along with extra circuitry (which is explained in the ‘Graphics’ section).

The type of memory chips (GDDR3) is the same one found in the Wii and PS3. Conversely, the Xbox 360 gets the crown for including the largest amount. In fact, it’s been reported that Microsoft initially planned to house 256 MB, but later doubled the amount out of fear for Sony’s upcoming competitor [20]. Though, unlike Sony, Microsoft was extra sensible with the retail price, so it had to cut down on other features. That’s why the hard drive was made optional. Furthermore, Microsoft expected Samsung (its memory supplier) to deliver their chips operating at 1.4 GHz but then settled for 700 MHz at the time of shipping the console.

Memory Controller

With all being said, how can Xenon access this memory? Well, the CPU communicates with the GPU through an interface called Front-side Bus, this combines serial and parallel communication models to keep costs down and reduce latency as much as possible [21].

On the outside, there are two unidirectional lanes named ‘PHY’, each is made of 16 buses that operate at the exceptional speed of 5.4 GHz [22]. In there, information is transmitted in serial form. Internally, however, the CPU and GPU only understand whole words. Thus, both endpoints are tasked with serialising the data before sending it through PHY and/or deserialising it after receiving it. The CPU’s inner interface is 64 bits wide and runs at 1.35 GHz, while the GPU’s is 128-bits wide and runs at 675 MHz [23]. If we do the math, both lanes provide a bandwidth of 10.8 GB/s.

The Front-side bus route only takes you to the GPU. So, between the GPU and the GDDR3 chips, two memory controllers inside the GPU manage this connection using one 1024-bit bus each. To reduce latency, the memory controllers use address tiling for GPU-related operations and path-finding to reduce CPU congestion. In general terms, Microsoft states that there’s a bandwidth of 22.4 GB/s between GPU and memory.

It’s all jolly on paper, but let’s not forget that the CPU still has to walk a long road to get to memory. To give you an idea, if you grab PIX (the CPU profiler included with the SDK) and run the sample tests that come with the utility, you’ll see that for every cache miss, the CPU spends ~600 cycles to get to memory! This is one of the features of UMA-based systems you don’t see marketed very often :), but also helps you understand why cache is so critical.

Inside Xenon: Programming styles

With all being said, how can anybody take advantage of this fascinating chip? Well, there’s only one way: Multi-threading.

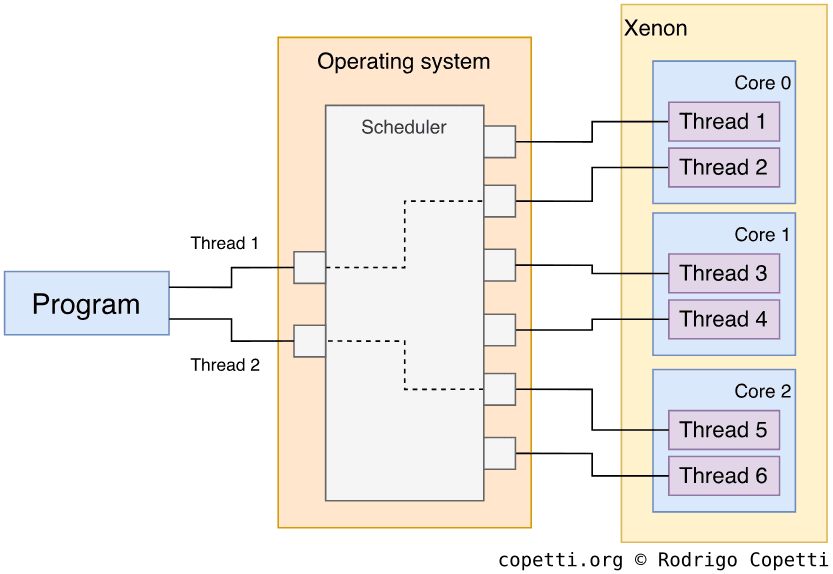

From the programming perspective, a CPU that’s made of multiple homogeneous cores sharing the same memory is what we call a Symmetric Multi-Processing (SMP) design. This conditions how the application will be designed and implemented. As of 2022, this is the de-facto layout for consumer multi-core CPUs (i.e. x86 and ARM) as well.

SMP programming abstracts access to physical CPU cores with the use of ‘virtual threads’. A virtual thread is a sequence of instructions the programmer defines. Threads can then be submitted to a ‘scheduler’ for their execution. The scheduler is another program (often part of the operating system) that handles how virtual threads are dispatched to the physical CPU cores.

This abstraction layer allows the programmer to avoid discriminating against the type of core used (therefore making the program cross-compatible with similar platforms) and hard-coding the number of cores (making it scalable).

It’s no surprise that this style became a standard in future console generations, as it’s easier to scale and program with symmetric systems than asymmetric ones (i.e. Cell). The latter often depends on unusual programming styles, eroding compatibility with other systems.

Also, it’s worth mentioning that, while SMP programming is not necessarily restricted to one platform, Xbox 360 developers will only be writing threads for Xenon (which provides a total of six threads). This enables them to optimise their multi-threading design for the Xbox platform as well.

Graphics

Here’s a peculiar aspect of Xenon. While the chip, by itself, incorporates interesting technology to make it a powerful contender against the competition, Xenon was never conceived as a one-man band. To make this console, as a whole, extremely competitive and long-lasting, Xenon was closely bonded to another chip, the GPU.

The graphics chip is designed and manufactured by no other than ATI, Nvidia‘s direct rival. To put it into perspective, a new company called ’ArtX’ was set up by former SGI employees who developed the Nintendo 64’s graphics chip, the Reality Co-Processor. Afterwards, Nintendo hired them again to produce the GameCube’s Flipper chip… at the same time ATI was in the process of acquiring them [24]. By then, ATI was competing in the PC arena with their ‘ATI Rage’ graphics cards and will soon inherit Flipper’s engineers. Fast forward to 2005, Nvidia (now supplying Sony) was now facing ATI again in the console market.

Good old competition, one can only wonder what new innovative product will come out of it.

Overview

Since the early naughties, Nvidia and ATI have been trying to outmatch one another in terms of performance, often by adding incremental improvements to their flagship brands.

Nvidia enjoyed considerable leverage after the introduction of programmable pixel pipeline which later became part of the OpenGL and Direct3D specification. Thus, ATI had no other choice but to follow suit. However, in 2003, ATI recovered its user base after Nvidia’s anticipated ‘GeForce 5’ line disappointed Direct3D 9 users, who were expecting better performance and functionality from Nvidia’s flagship card [25]. As a result, attention shifted towards ATI’s Radeon 9000 series.

These events allowed ATI to keep the crown for a while longer, but unbeknownst to Nvidia, ATI had been working on a new disrupting ingredient that could hold Nvidia for another decade. This project eventually materialised in the form of Unified Shaders and debuted in no other than the Xbox 360, with the new graphics chip called Xenos.

A new foundation on the way

You’d be surprised that Microsoft’s push for homogeneous computing also dragged the GPU into this mix.

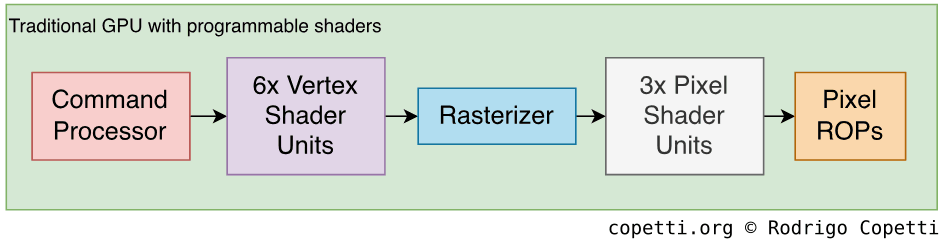

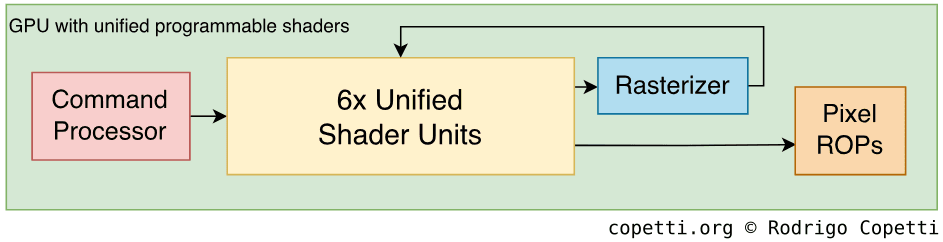

You see, there was a time when GPUs were mere rasterisers with ‘take it or leave it’ functionality, meaning they provided a fixed set of functions and programmers could either activate them or not. Later on, thanks to SGI’s innovations, workloads were offloaded from the CPU thanks to the new programmable vertex pipelines. Finally, the ‘mere rasteriser’ definition was rendered obsolete (pun intended) as Nvidia promoted a new stage called programmable pixel shader which gave programmers the liberty to control what happens after rasterisation.

This pattern shows us that, as GPUs grow in performance and functionality, they eventually open up to allow developers to implement the exact functionality they seek. However, this also increases the overall complexity of the silicon.

Over the years, both vertex and pixel pipelines kept enlarging to accommodate current needs, with new scalability problems emerging. Space, costs and heat emissions have a limit. So, which tasks should be prioritised? Vertex operations or pixel effects? A weak vertex pipeline will stall the pixel pipeline. Alternatively, a disappointing pixel unit won’t attract users with its dully-composed frames.

Thus, architects at ATI took two steps back and asked themselves ‘Is there any way to simplify this model instead of adding more transistors on top of it?’ which later became ‘Why are pixel and vertex pipelines segregated?’. And so, the two stages were ultimately merged into a single -unified- block of circuitry. This is what we call the Unified shader model and a GPU implementing it still provides both programmable vertex and pixel pipelines, but the circuitry used for computations is shared.

The new model has two primary benefits: a more balanced scaling (as it will now improve both pixel and vertex pipelines to the same degree), and programmers can now develop shader programs that are not constrained by the limitations of an individual pipeline type. Though the latter will require major changes in the API to standardise its behaviour and availability, which won’t arrive until 2006 with DirectX 10 or in 2010 with OpenGL 3.3.

Suffice to say that the unifier shader model is now another standard in the graphics industry.

Architecture of Xenos

To construct Xenos, ATI borrowed material already present in their consumer products. Though it’s hard to say which existing card they based Xenos on. Wikipedia pairs it with the ‘R520’ core (found in the Radeon x1800) [26], though I find it hard to believe as the R520 contains fundamental differences (related to the new unified architecture) that make me doubt about such relation. In the absence of any reliable source, I turned to the Xenia emulator Discord where I luckily received a lot of input from the community, especially TriΔng3l, who works in emulating Xenos.

In essence, Xenos is based on R400 (also known as ‘Crayola’), a new architecture from the ground up that never materialised in the form of a consumer card (except Xenos, being the only incarnation to this day). Instead, ATI shipped R500-based cards to PC users, which are a continuation of the R300 architecture. Curiously enough, some R520 cards incorporated part of Crayola’s technology, but were marketed as ‘ATI Avivo’ and only used for accelerating video decoding.

In the end, ATI brought the unified shader model to the masses through their new R600 architecture (an evolution of R400), also known as ‘TeraScale’, released in 2007 with the Radeon HD 2000. And the rest is history.

Interestingly enough, the R400 branch carried on in the smartphone world with the ATI Imageon Z430 [27], later called Qualcomm Adreno 200, which also went through many iterations. This is another example of innovative technology that finds its way into the mobile market!

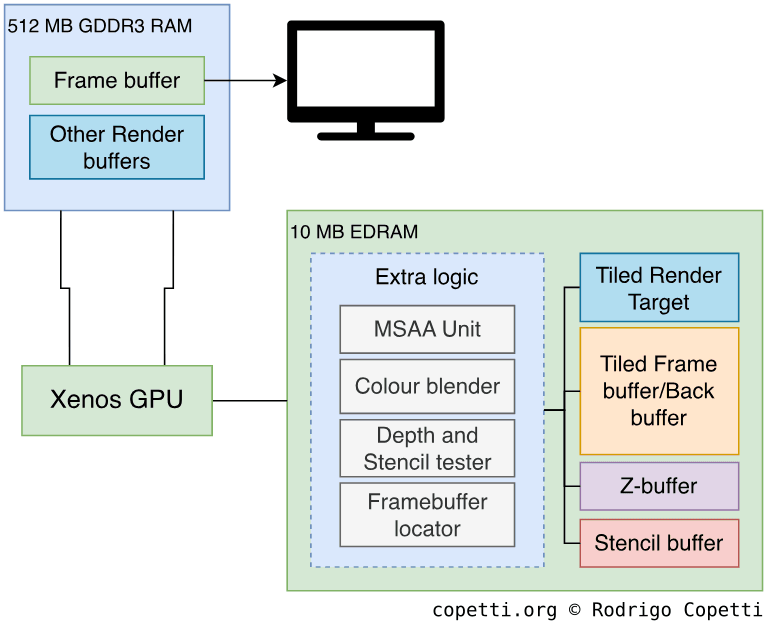

Organising the content

Another unusual element from Xenos is its triple memory architecture (so much for emphasising the UMA…). Xenos relies on two different chips to render graphics, one is the aforementioned 512 MB of GDDR3 DRAM (which is shared with the CPU) and the other is a smaller but way faster memory chip residing within the same package (which only Xenos has access too). The latter piece provides 10 MB of Embedded Dynamic RAM (EDRAM) [28]. Curiously enough, EDRAM is not a new ingredient, having been found in the Graphics Synthesiser, the Graphics Engine and, most importantly, Flipper (also ATI’s invention).

Those 512 MB store most - if not all - the materials Xenos needs to render a frame, including textures, shaders and many types of buffers as the game sees fit. On the other side, the 10 MB of EDRAM are left for small elements that require rapid access, such as the Z-buffer, the stencil buffer, the back buffer (intermediate frame buffer) and any other custom buffer if needed. This mitigates congestion from the shared GDDR3 RAM and speeds up operations that make use of those buffers.

As if this wasn’t enough, there’s a third source that can feed the GPU, and that is a direct line to the CPU! Unlike anything seen before, the CPU can stream commands and geometry without going through the traditional steps of storing command buffers in external memory, thereby saving once again traffic from main RAM. This is what Microsoft advertised as Xbox Procedural Synthesis (XPS) and made possible by two changes [29]:

- Firstly, the CPU’s front-side bus was adapted so the GPU can directly fetch data from the CPU’s L2 cache (where the CPU may procedurally generate the geometry) in blocks of 128 Bytes (the size of a cache line).

- Secondly, a separate cached location was added into Xenon so the GPU can notify its current state to the CPU as fast as possible. Microsoft calls it the Tail pointer write-back and keeps both components in sync while the CPU updates the L2 cache and the GPU pulls from it. According to Microsoft, this routine provides a theoretical bandwidth of 18 GB/sec [30].

Overall, this synergy is what has enabled the Xbox 360 to achieve such a high level of performance without requiring overpriced hardware.

Constructing the frame

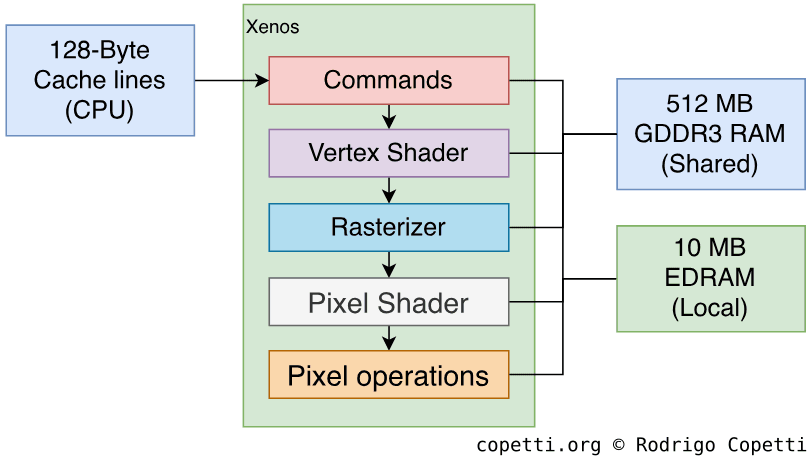

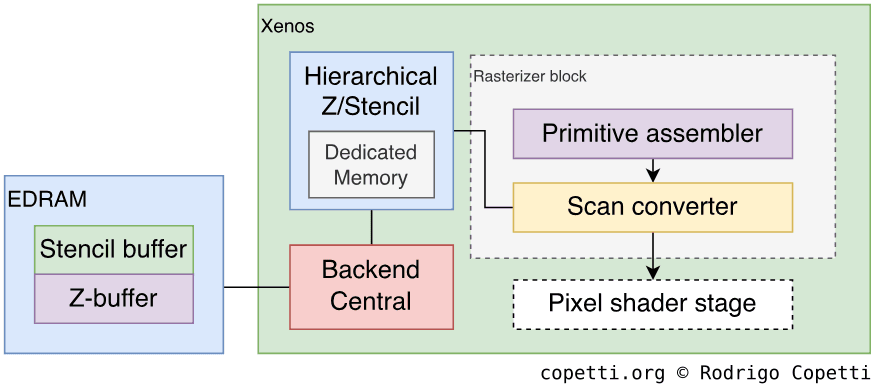

Having said all that, how does Xenon actually render a frame? Well, similarly to other GPUs in the market, there are many steps involved. Take a look at this diagram of Xenos’ pipeline.

As you can see, the pipeline stages are not different at all compared to other graphics chips that don’t employ the unified shader model. This is because the actual change happens at the circuitry level and not at the API level (for now). This way, developers are not forced to learn new techniques that will disrupt their traditional methods, but they’ll soon find that the new underlying design will benefit them in terms of performance and extra functionality (on top of the ‘traditional’ one).

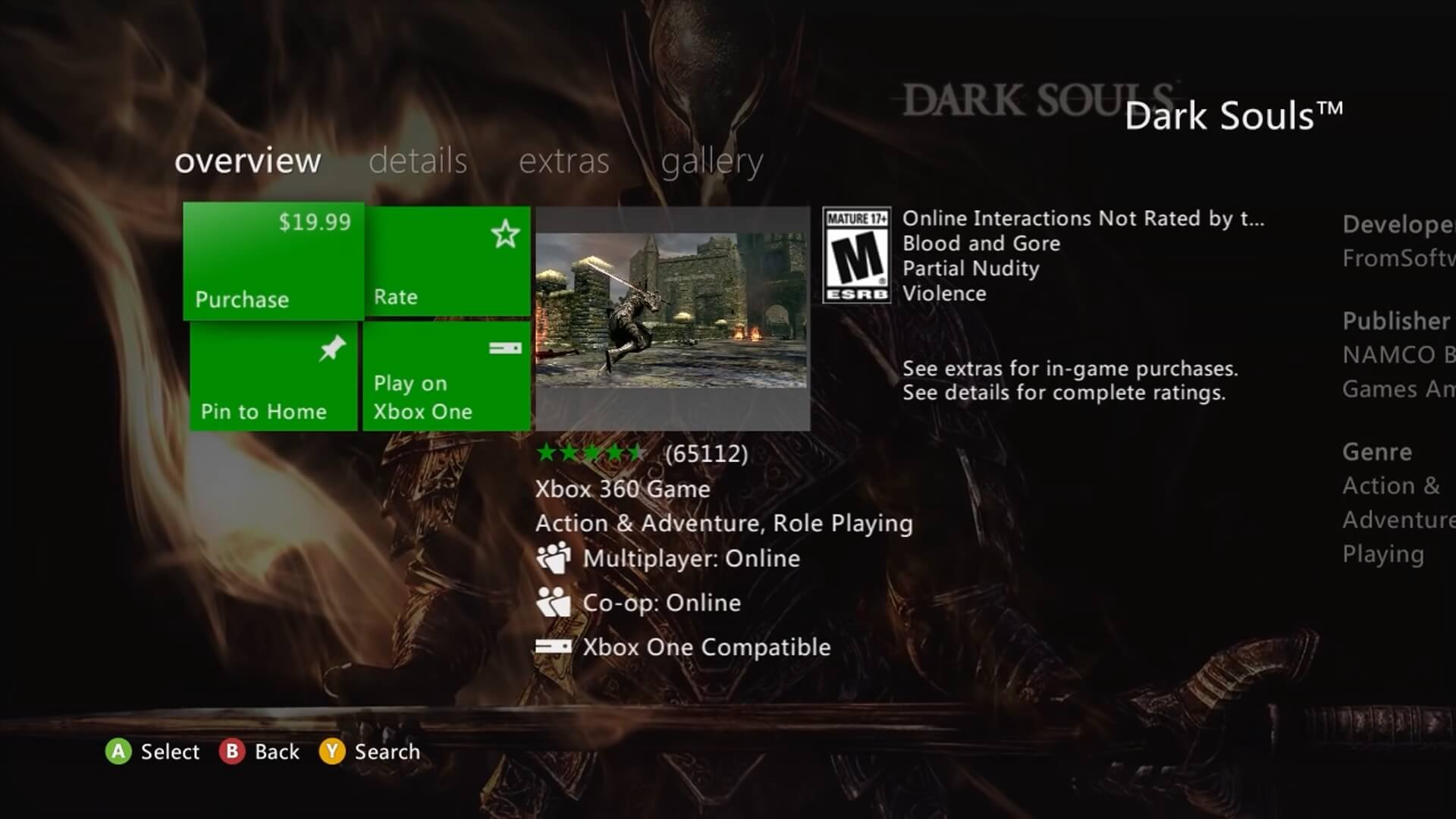

Conversely, this GPU is strongly aligned to a proprietary API developed by Microsoft called Direct3D 9. This API has enjoyed increasing adoption in the PC market due to its wide compatibility rate with off-the-shelf graphics cards, making the job of game developers a bit more enjoyable. And even though Xenos will also expose some behaviour not seen in the off-the-shelf market, Direct3D is the only high-level API that Microsoft provided to talk to Xenos. So, what we find in the Xbox 360 is a semi-customised version of Direct3D 9 that makes room for the extra functions of Xenos. Curiously enough, Direct3D influenced the design of Xenos in the same way Xenos influenced future revisions of Direct3D (starting with version 10).

Now it’s time to make a full dive and see how this pipeline works, just like we did in the other articles.

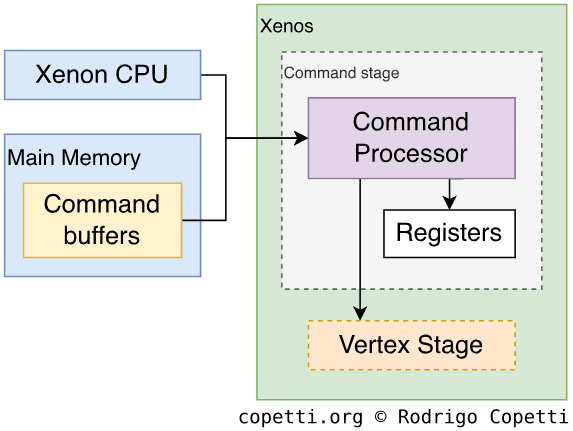

Commands

Welcome to the tour of the 12th polygon factory of this series. As always, the starting point is the command stage. Commands tell the GPU what, where and how to draw something on the screen. This time, however, commands may be stored in Main Memory (within a buffer) or directly streamed by the CPU. Both are subsequently fetched by the Command Processor [31], which parses it and forwards it to the respective unit that performs the required operations (as commands may encode different types of instructions, such as ‘draw a triangle’ or ‘set X register’).

It’s worth mentioning that by this generation, the traditional practice of using Display Lists for composing commands has been long superseded by a new structure called Command Buffer (as OpenGL and Direct3D call it). While both terms sound similar, the new entity makes room for new operations that weren’t originally envisioned when Display Lists were conceived (primarily related to vertex, pixels and GPU control). As the APIs evolve, Command Buffers are adapted to reflect modern needs, while Display Lists have been deprecated since 2008 (OpenGL removed them with OpenGL 3.2) [32].

Furthermore, Direct3D 9’s command buffers (found in the official SDK of the Xbox 360) provide the option to embed an interesting data format called Index Buffers. This enables developers to reuse existing vertex points to avoid duplicating geometry data in memory [33].

Finally, this GPU can also conditionally execute commands depending on arbitrary conditions set by the developers. In Direct3D’s world, this is called Predication and saves the GPU from processing geometry that may be occluded, for instance.

Vertex Shader

Since the times of Flipper (or even the RCP, as it shared its core team members), ATI maintained the initiative of providing a geometry block to accelerate vertex operations. With Xenos, it is now fully programmable using Direct3D’s High-Level Shader Language (HLSL), which is similar to C but used for implementing vertex shaders without needing assembly, although the latter is still possible.

Both Xenos and RSX implement the Vertex Shader Model 3.0 (vs_3_0) specification, which outlines a common set of capabilities and limitations. This includes providing 512 or more slots for instructions, branching opcodes and support for texture fetching, among others. The difference, however, is that PlayStation 3 programmers must use Nvidia’s CG compiler (once a collaborative work with Microsoft’s HLSL) while Xenos developers rely on Microsoft’s toolkit instead, and thus use Direct3D’s HLSL compiler.

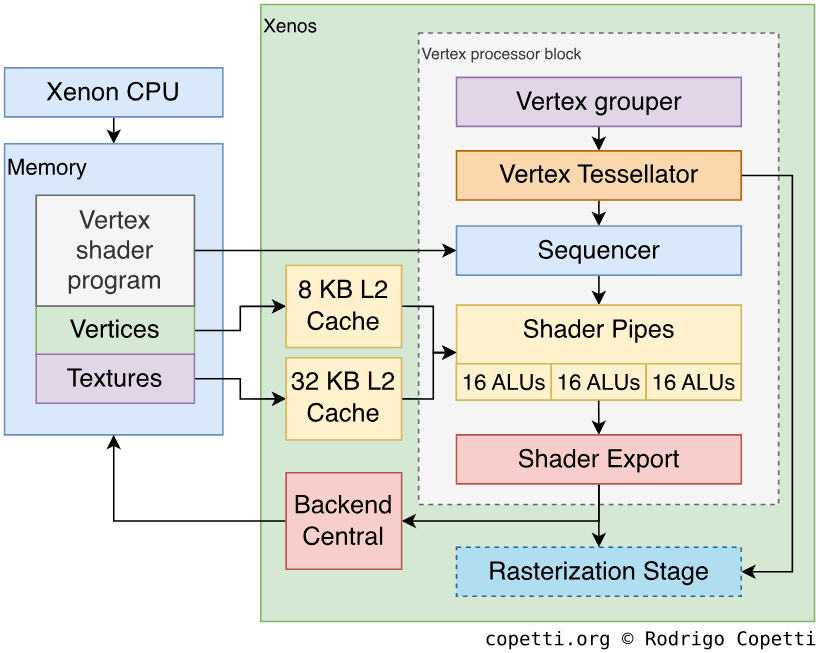

Furthermore, let’s not forget that the hardware carrying out those operations relies on a new formula. The new unified design means vertices are processed through a shared but bigger pipeline, which works as follows:

- Based on the received commands, the Vertex grouper reads the memory addresses where vertices are located in main RAM and the Tessellator transforms non-triangular geometry (i.e. quadrangles and parametric curves) into triangles, so the rest of the GPU can process it. The latter can also split triangles into smaller primitives, so bigger detail can be achieved without consuming extra bandwidth. The grouper can read 16 Bytes of data per clock and caches the last 14 vertices processed.

- The Sequencer loads the vertex shader and pulls vertex data using 8 KB of cache.

- Now that all vertex data is ready to be processed, 3 Shader Pipes (groups of 16 ALUs, each) execute the shader program. Each shader pipe receives batches of 64 Bytes. Vector-to-vector arithmetic takes four cycles while vector-to-scalar operations take only one.

- The Shader Export buffers the results and sends them back to the start of the line where Primitive Assembler picks them up for rasterisation. Alternatively, the shader export can forward the results to the Backend Central, where they are exported to main RAM.

- The latter capability means a shader can write raw data into main RAM, remember this when we reach the ‘Anti-piracy’ section…

Rasterisation

Once the primitives have been transformed or subdivided as requested, the rasteriser begins the transformation to pixels.

Firstly, the Primitive Assembler receives vertex data from the Tessellator and/or Shader Export and begins building triangles out of vertices. This operation takes one cycle, except when vertices require clipping and culling applied (to discard unseen triangles outside the bounding area).

Secondly, the Scan converter receives triangles and packs them into 8x8 pixel blocks called tiles (yes, the same word appropriated by 2D consoles…). The converter generates one tile per cycle and sends them to a dedicated unit that performs early Z and Stencil test. So far so good? Well, here’s the interesting part: the latter unit implements a new and efficient rejection technique called Hierarchical Z (Hi-Z).

Instead of testing each pixel of the triangle, Hi-Z evaluates groups of pixels (2x2 pixels in this case) by calculating the maximum and minimum Z-value among the four pixels. Then, if the maximum z-value of the quadrant is less than the respective value stored in memory, the whole portion is assumed to be occluded and the quadrant is discarded [34].

The Hi-Z block uses dedicated memory for these operations, this memory can store up to 16 different Z-values for Z-testing 64 pixels per cycle. The downside is that available memory only allows Xenos to perform Hi-Z if the framebuffer’s resolution is no greater than 1280 x 720 pixels along with MultiSampling Anti-aliasing with up to two samples (2x MSSA) activated.

Finally, the scan converter gets back groups of 2x2 blocks (so 16x16 pixels in total) and sends them in batches of 64 pixels to the next stage, where the pixel shader adds the eye-catching effects.

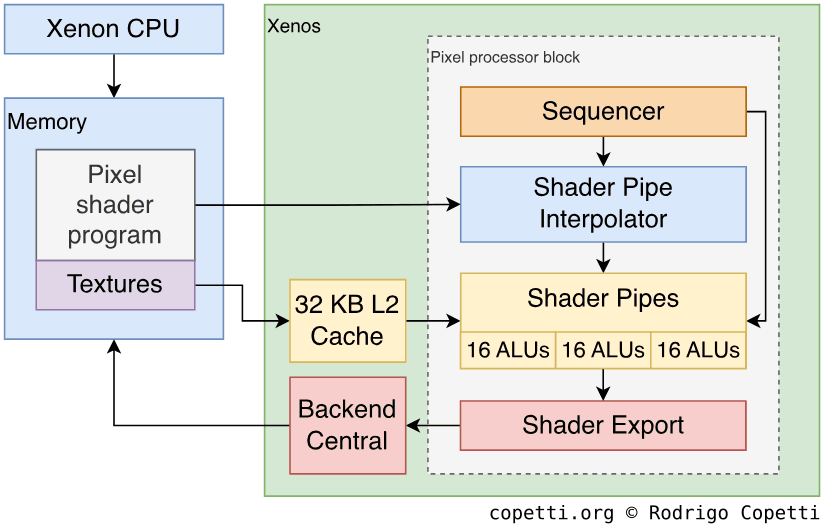

Pixel Shader

To execute the pixel shader, Xenos re-uses the same components of the vertex pipeline with slight detours. Similarly, HLSL’s Pixel Shader Model 3.0 (ps_3_0) specification states what developers can accomplish at this stage, which is not significantly different from Sony’s counterpart. Nevertheless, since the underlying foundation has been simplified (well, unified), resources have been homogenised, improving the balance of performance across all stages.

That being said, the pixel stage works as follows:

- The Sequencer loads the pixel shader program and forwards pixels to the interpolator.

- The Shader Pipe interpolator interpolates colours between four vertices (creates intermediate values to fill in the gap between two extremes) that will be used by the pixel shader. It can generate 16 colours per cycle.

- 32 KB of Texture cache fetches and decompresses textures from main RAM, then, the Texture pipes send up to 16 texels per cycle to the shader pipes. The texture pipes can instantly apply bilinear filtering, but they also offer trilinear and anisotropic filtering at the cost of extra cycles.

- The 3 previous Shader pipes are now used to execute the pixel shader, each pipe operates vertex made of 16 2x2 pixel blocks coming from the interpolator. The ALUs can process 32-bit floating-point numbers (IEEE 754 compliant) without penalties.

- The Shader Export and Backend Central forward the results to memory. The latter outputs two blocks of 2x2 pixels (8 pixels in total) per cycle. Other kinds of data that can be exported include new Z-values for the Z-buffer and arbitrary data to main RAM.

- The result from the shader export doesn’t necessarily have to be the final frame buffer, games with lots of scenery often render multiple buffers (called ‘render targets’) that are used to derive the final frame. This is called Multiple-pass rendering and Xenos supports outputting up to four Multiple Render Targets (MRT) at the same time [35].

Pixel Operations

This is as far as it goes for rendering, but one thing we haven’t explored yet is how those 10 MB of EDRAM benefit all of this. Well, this chip is very special, because it contains internal logic to perform automatic Multisample Antialiasing (MSAA) along with Depth and Stencil testing. Its internal bandwidth (between its internal logic and internal memory) provides an absurd 256 GB/second, which makes it very attractive for storing intermediate buffers (as opposed to storing them in main RAM).

The only drawback is that 10 MB is not enough for storing large buffers, especially those needed for rendering high-definition frames (1280x720 pixels wide with 2x MSAA enabled), let alone 1920x1080 frames. But fear not, as ATI supports tiled rendering (the same featured in the Dreamcast!). This enables to render portions of the screen, store the results in EDRAM (for performance reasons) and, finally, reconstruct the tiles in main RAM to form the final frame. Tiled rendering became so critical that Microsoft took a step forward and devised Predicated Tiling [36], a function in Direct3D that automatically sets up and optimises the rendering pipeline specifically for tiled rendering. This prevents developers from manually programming each pipeline stage to handle tiles.

Thanks to the new bandwidth achieved, game designers may push for a level of quality that otherwise would’ve been unfeasible with a traditional rendering system. This includes applying extended antialiasing methods (4x MSAA) or even High-dynamic-range (HDR) rendering. You see, HDR requires 64-bit pixels, where each channel is encoded as a 16-bit float. This has always been very expensive in terms of bandwidth, but in exchange, it provides the right precision to obtain realistic lighting and colour effects, something the Xbox 360 can now enjoy.

The impact on the industry

The state of the industry after 15 years has demonstrated that the unified shader model was meant to become another building block within GPUs. Interestingly enough, when Direct3D 10 and OpenGL 3.3 debuted in 2006 and 2010, respectively, not only did they standardise this model, but they also defined new features and applications that were now possible to implement. For instance, a new pipeline stage called Geometry shader was added in Direct3D 10 to expand the uses of the tessellator.

On a related note, Xenos also introduced new encoding methods for storing HDR pixels using no more than 32-bit values (thus, saving bandwidth and storage). One of their proposals was to encode the three primary colors using 10-bit floats and leave the remaining two for the alpha channel (transparency) [37]. A year later (2006), Direct3D 10 and a new OpenGL extension took this idea further and implemented the (now standardised) ‘packed float’ structure, consisting in encoding Red and Green using 11 bits and Blue using 10 bits [38].

Similarly, over the next years since the console’s release, the concepts of Xenos’ shader exports would be embraced by many new APIs, namely Apple & Khronos’ OpenCL, Nvidia’s CUDA, Direct3D 10’s DirectCompute and OpenGL 4.3’s Compute shaders. All of which provide a platform to access the power of GPUs without necessarily having to render anything, just perform computation using the fast shader pipes. Overall, this was another great leap for General-purpose GPU programming.

Now, if you wonder if any of these advancements were later incorporated into the Xbox 360. I’m afraid by the time this console debuted, the unified shaders were still a relatively new concept. So, unfortunately, none of the consequent developments (i.e. Direct3D 10) got ever back-ported to the Xbox 360. But hey, that’s a legacy left for the next generation of consoles to enjoy!

On the other side, the PC market experienced a different revolution that strangely didn’t originate from ATI. It turns out Nvidia won the race on becoming the first company to ship a graphics card using the unified model, I’m referring to the GeForce 8 series (and its Tesla architecture) that landed in 2006 [39]. Ironically, it was the same year the PlayStation 3 arrived (also powered by Nvidia’s technology, though with an older architecture…).

Video Output

Unlike the PlayStation 3, which arrived a year later, the release of the Xbox 360 in 2005 got caught up in the middle of a transition from analogue video (i.e. RGB and composite) to digital (i.e. HDMI), so the first shipments of the console didn’t bundle the famous HDMI connector that quickly displaced the analogue video salad.

Instead, the first revision (called Xenon, like the CPU) is only equipped with a multi analogue socket called ‘A/V’. This carries all the signals previously featured with the original Xbox, with the addition of VGA-compliant pins [40] (its predecessor had the wires in place but, for some reason, were never powered [41]).

Later on, in 2006, the follow-up motherboard revision called Zephyr ultimately added an HDMI socket to catch up with Sony’s quality of signal. Internally, the original video encoder (known as the ANA chip) had been replaced with the ‘HDMI ANA’ (or HANA) block [42].

As outdated as this may seem today, Microsoft still required developers to consider their games being played on CRT screens, which are prone to overscan. Thus, games couldn’t place any important indicators within the Danger Zone.

Short-lived features

Following the requirements of the Video Electronics Standards Association (VESA), Microsoft released a software update in November 2008 to support 16:10 aspect ratios, although only available through the VGA signals. Games were still only required to support 16:9 and 4:3 ratios, so using 16:10 would show a black backdrop (a.k.a. letterbox). Curiously enough, the operating system contains routines to allow games to detect whenever 16:10 is activated, though they were never made public.

Additionally, Microsoft shipped a software update in May 2011 to add support for 3D TVs, much like the PlayStation 3 did.

New attitudes towards resolutions

Even though the video encoder can broadcast signals in a multitude of formats, including PAL, NTSC, 720p and 1080p, Microsoft pushed publishers to focus on 720p for two reasons:

- The general consensus from 2005 predicted that most consumer TVs will soon be equipped with high-resolution and widescreen screens.

- Since it would take time to master Xenos’ capabilities, launch titles were assumed to not use all of the GPU resources. Thus, games painlessly added HD support to compensate.

With the same rationale, why is 1080p not the focus instead? Well, 1080p puts a significantly higher workload on Xenos, which limits effects like anti-aliasing. Instead, Microsoft suggested developers to render at 720p and direct the internal video scaler to upscale the frame to 1080p, if required. To assist with this, Microsoft released another software update in October 2006 to enable 1080p output (initially, only 1080i had been available).

Audio

As CPUs evolved to become multi-core jack of all trades, the grounds for housing dedicated audio hardware slowly dissipated. In the end, Microsoft decided that the Xbox 360’s audio department would be the responsibility of the CPU, and as such, the audio pipeline was implemented through software. So, the operating system provides routines which games access through the official SDK. This brings in new advantages, as the general-purpose capabilities of CPUs are not restricted to a fixed set of audio functions.

A year later, the PS3 would follow suit, and thus cement this practice across the video game industry.

The hidden audio chip

Conversely, in the case of the Xbox 360, we find a huge exception to this rule: Microsoft fitted a hardware audio decoder on the motherboard [43]. Although, this circuit is hidden within the Southbridge chip (explained further in the ‘I/O’ section) and it only supports one codec called Xbox Media Audio (XMA). The latter is a variant of Microsoft’s proprietary Windows Media Audio (WMA), which you may have heard about already. In any case, why was that codec so crucial that Microsoft invested extra hardware in a console already facing budget cuts?

A codec-rich industry

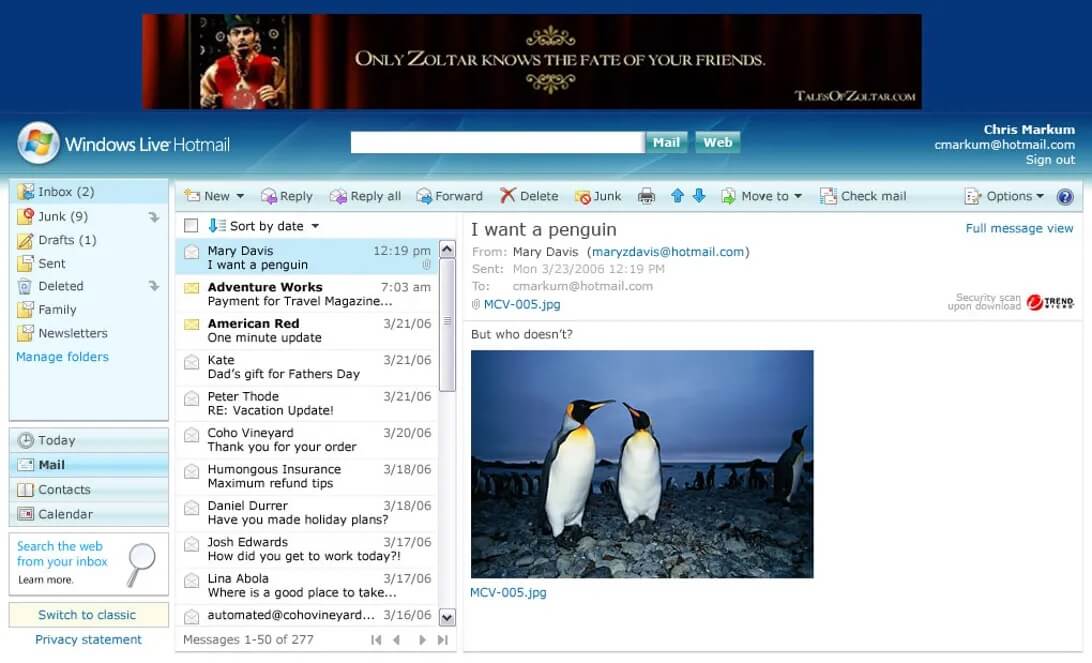

Back in the naughties (and even the late 90s), during the rise of the World Wide Web and affordable multimedia products (e.g., accelerator cards, SIMD-capable CPUs, and fast network bandwidth), many companies that were once narrowly focused on productivity software suddenly ventured into a new area of multimedia services.

It so happened that, all of a sudden, users began asking to watch full-motion movies on a PC, listen to music while working on a spreadsheet, and even compile their own audio CDs (the iconic rip and mix). We, of course, take all of this for granted now, but mind these ‘abilities’ had to be implemented at some point in history. Initially, they were delivered through third-party software (Nero and Winamp, to state a few) and later bundled with the operating system: Windows XP had built-in CD burning features, albeit mediocre, and Mac OS X 10.1 integrated iTunes.

Now, if we focus on the events surrounding the music world and its never-ending sharing systems, we also see that the MP3 became the de-facto codec for transmitting music [44] and that brought huge demand for media players that could decode MP3 (well, technically, MPEG-1). That being said, what was Microsoft’s response to this trend? Well, develop another codec to displace MP3, a new format called Windows Media Audio or ‘WMA’ [45].

One more push for WMA

Unfortunately for them, the adoption of WMA was not as popular as MP3, presumably due to Microsoft’s licensing schemes. To top it off, Microsoft later fragmented their user base by releasing non-backwards compatible revisions and offering multiple tiers. Yet, the company still kept pushing for adoption by other means, for instance, through DirectX’s audio playback libraries, namely ‘DirectShow’ [46].

You can see now that it’s not difficult to put two and two together. The original Xbox was conceived as a ‘DirectX-compatible console’ and, while one could debate about such statement, the same slogan also applied to the Xbox 360. So, it’s no mystery that WMA carried on in this console.

However, Microsoft didn’t bring WMA in its current form. Instead, they enhanced it to make it an attractive codec for game studios (already adopting Sony’s ATRAC3). In essence, Microsoft grabbed the high-end WMA tier (called ‘WMA Pro’) and added more levels of compression that were favourable to the bandwidth capacity of the Xbox 360. Finally, they renamed it Xbox Media Audio or ‘XMA’.

For the coup de grace, Microsoft added dedicated circuitry to offload CPU cycles during decompression tasks, so the CPU can focus on other parts of the game.

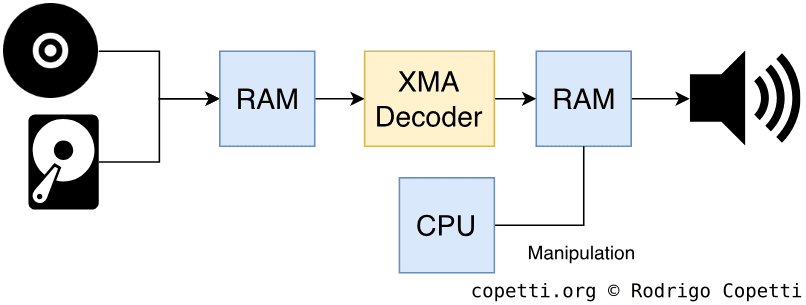

A look at the XMA accelerator

In terms of functions, The XMA decoder can decode up to 5.1 audio channels with a sample rate of 48 kHz and a resolution of 16-bit. No surprises here!

Moving on, the decoder works as follows:

- It starts by reading XMA-encoded data from main RAM.

- Decodes it.

- Outputs PCM data, ready to be streamed, in an arbitrary location in main RAM.

- Finally, the CPU can apply effects on it and/or forward it to the audio DAC for hearing.

All of this is abstracted with the use of Microsoft libraries, which handle how data is streamed, optimised in cache and moved around in memory. Developers have multiple APIs at their disposal, each offering thinner-to-thicker layers of abstraction. Be as it may, the thinnest API won’t provide direct access to the XMA decoder, as it’s still a proprietary and undocumented block of circuitry, after all.

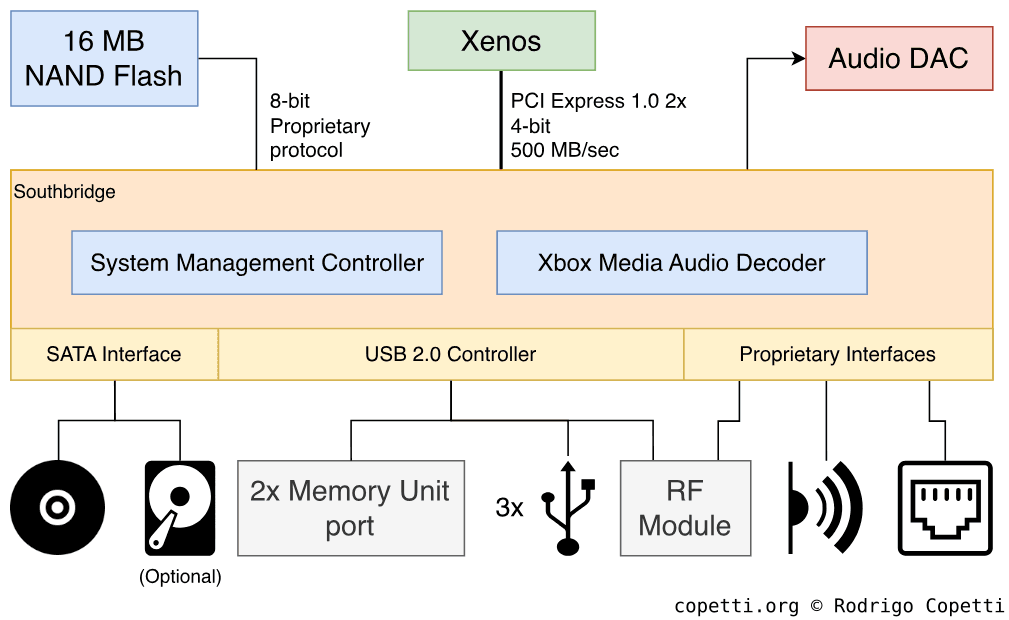

I/O

Following in the footsteps of the original Xbox, all I/O operations are handled through a thick and opaque chip called Southbridge (though in various documents I’ve seen it referenced as ‘I/O chip’ or ‘XBS’ as well). The Southbridge connects to most, if not all, internal and external interfaces. This chip is only connected to the GPU (not the CPU), so Xenon has to go through Xenos to reach it and subsequently request data from any socket.

The Southbridge communicates to Xenos using the PCI Express protocol, composed of two unidirectional serial buses, one for each direction. In the case of this console, each bus can transfer up to 500 MB/sec [47].

Clever L2 access

To keep up with the demand, the Southbridge can write to main RAM. Consequently, there needs to be a mechanism in place to maintain data coherence between the CPU’s caches and the changes done by the Southbridge. Hence, the latter is equipped with an automatic trigger that flushes the CPU’s L1 and L2 if, and only if, the memory address the Southbridge wrote to had been cached by the CPU. Nevertheless, the CPU will have to cache that memory again, though programmers won’t need to worry about manually synchronising the CPU caches every time the Southbridge fiddles with main RAM.

The core of Southbridge

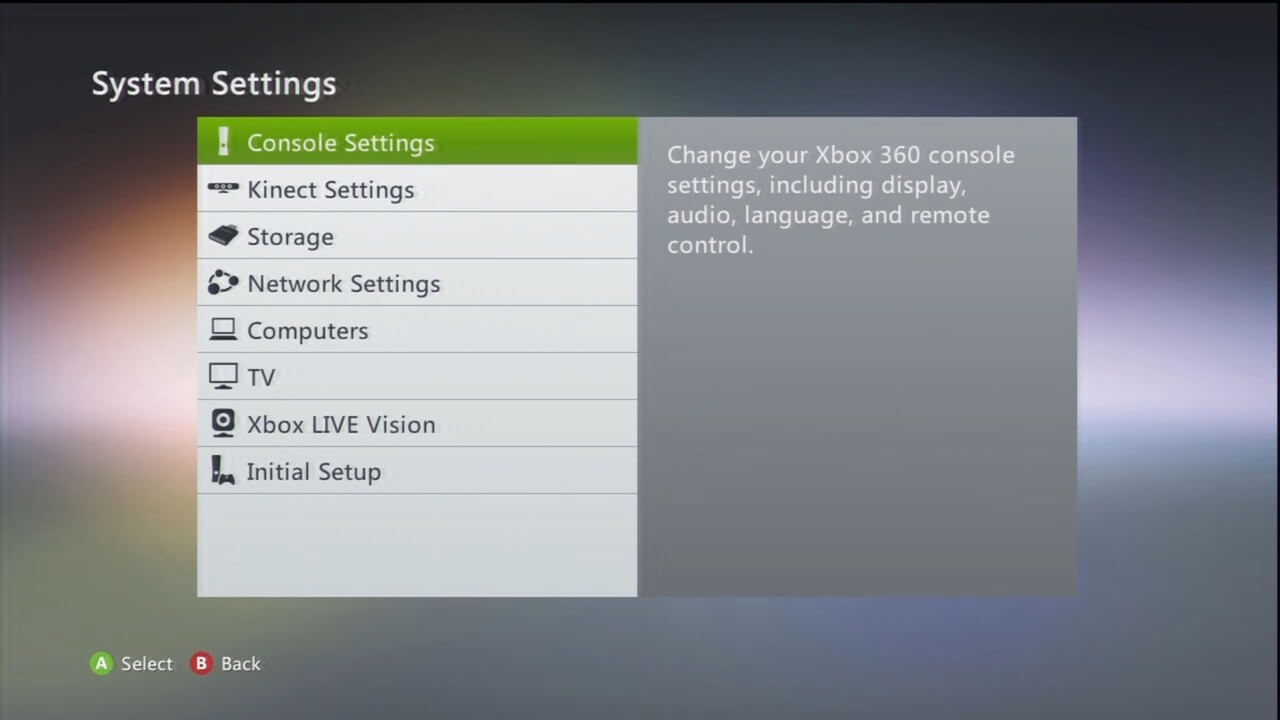

You’ve seen before that the abundance of services in 7th generation consoles has led to the inclusion of many black boxes. These are meant to offload most of (if not all) the security and I/O tasks away from user-accessible components like the CPU and GPU.

The Xbox 360 is no stranger to this. Hidden within the Southbridge chip there’s a component called System Management Controller (SMC) and, like the Wii, it draws current even on standby mode. The SMC abstracts lots of I/O operations, including power management, real-time clock, temperature control, LED control and the infrared sensor [48]. The CPU communicates to the SMC using a FIFO command buffer, though this task is restricted to the Kernel only (more about it in the ‘Operating System’ section). So, neither the user nor the game can fiddle with it.

Internally, the SMC is nothing more than a classic Intel 8051 microcontroller with its own ROM and RAM [49]. Upon getting power, it boots its internal program and proceeds to read from a separate NAND chip to fetch configuration files.

There are other interesting aspects of the SMC, but we’ll discuss them in due time (don’t worry, I’ll be waiting in the ‘Anti-piracy’ section…).

External interfaces

The set of external ports is not particularly overwhelming, but there are a fair number of them.

In any case, the console offers:

- Three USB 2.0 A sockets: one is found at the back of the console and it’s meant to connect to an external accessory (like an official Wi-Fi module) that Microsoft sold separately. The other two are on the front and can be used to connect wired controllers.

- With the arrival of the ‘Slim’ Xbox 360 model in 2010, an internal Wi-Fi card has since been bundled with (internally connected with USB as well) and two more USB sockets were added on the back.

- A special socket (combining USB and proprietary interfaces) for the RF module, also known as the front panel that lights up when the console turns on. This component also handles the communication between the wireless controllers (through a proprietary wireless protocol) [50].

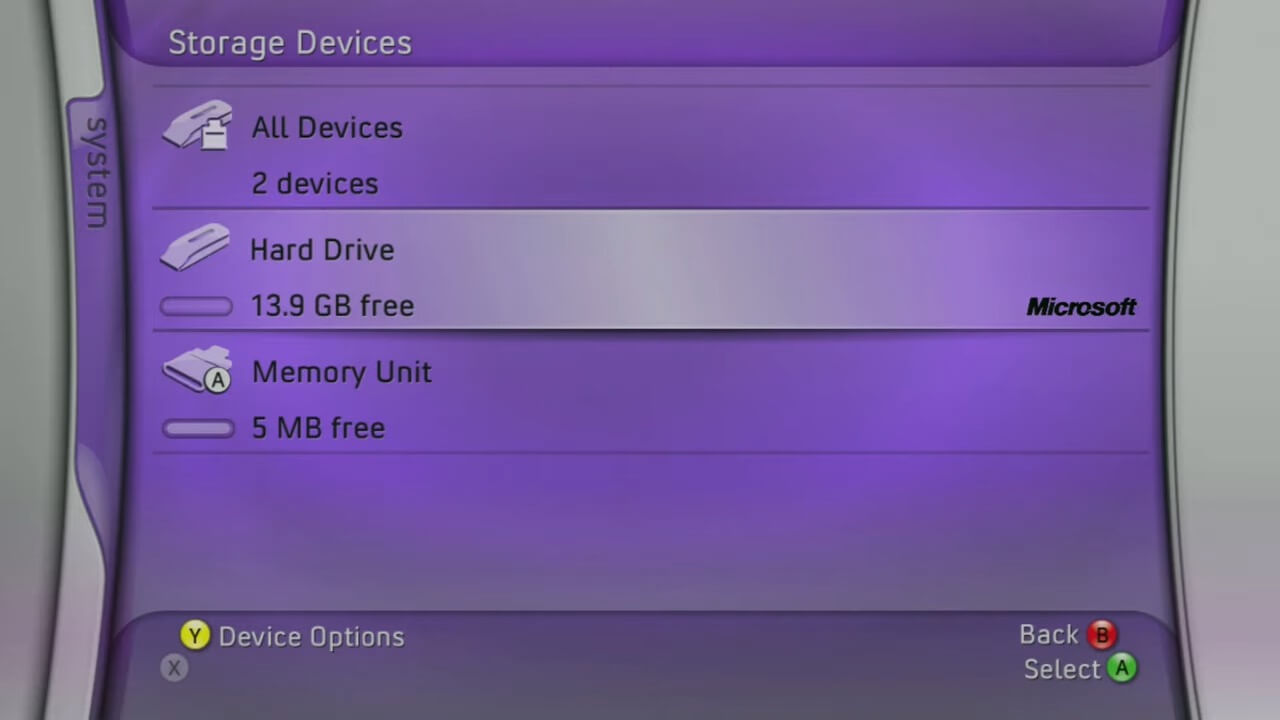

- Two Memory Unit ports: these are mangled USB ports that fit a Memory Unit, a proprietary Memory Card of up to 512 MB of size [51].

- An RJ45 port for Ethernet connectivity.

- Infrared Receiver to capture infrared light sent by an Xbox-themed remote controller (an optional accessory).

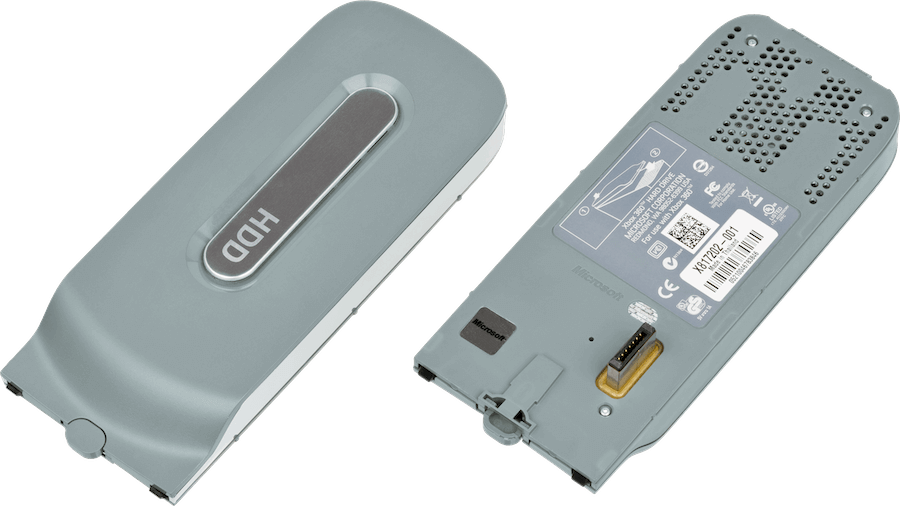

- One SATA II socket: mixed with power lines (resulting in a proprietary socket) and exposed at the top of the case (if the console is placed vertically) to connect the optional external hard drive.

Wired with a chance of Wireless

While Sony went straight for wireless controls using Bluetooth technology, the Xbox 360 shipped with different kinds of controllers depending on the ‘edition’ purchased (this doesn’t necessarily affect the motherboard revision, only the amount of accessories bundled with the box).

As you may guess, wireless controllers were only given out with the posh ‘premium’ editions, while the low-end & HDD-less ‘Arcade’ model shipped with a single wired controller (this time, using a standard USB A cable). Wireless controllers required two AA batteries, though Microsoft also sold a rechargeable battery block.

The console can handle four controllers at the same time, whether wireless or wired, but note that the console only provides three user-accessible USB ports.

Compared to the old duke, the controller doesn’t take two memory cards anymore, but it keeps the headphone jack (2.5 mm TRS type). The wireless model has a special socket on the front to plug the ‘Play and Charge’ cable, an optional accessory to connect wireless controllers to the console and charge the battery at the same time. The cable uses a proprietary bus layout composed of USB-compliant pins with additional undocumented ones [53].

Internal interfaces

These are the interfaces that the Southbridge handles to interconnect chips within the motherboard:

- One SATA II socket to plug the internal DVD drive.

- A proprietary 8-bit bus to communicate with a 16 MB NAND Flash chip.

- Another proprietary bus to talk to the Audio DAC.

That interactive accessory

I don’t tend to give too much attention to accessories because they deviate from the main focus of the article, but there is one special case where Microsoft dedicated an obsessive amount of marketing effort. They were even convinced that ‘gamepads are a thing of the past’ and it’s only a matter of time before this new product would eradicate current user interaction methods.

Well, that didn’t happen, but Kinect is still worthy of study. Released in November 2010 with huge fanfare, Kinect is a sensor bar (very different to the Wii’s sensor bar, Kinect’s ‘competitor-slash-inspiration’) that captures the user’s position, movement and voice in an effort to provide control of the game without requiring any physical object in the user’s hands.

The construction of this device isn’t anywhere simple, and as such, the sensor carries many forms of technologies:

- An RGB camera to capture images of the room and the player [55].

- A IR emitter and IR sensor that projects IR light and captures its reflection, respectively. This allows deriving a z-buffer of the room, thereby identifying the depth of objects.

- A microphone that listens to the player.

- A chip salad that handles the sensors and signals to produce meaningful data from it. This includes 64 MB of DDR2 SDRAM (as a working area), 1 MB of Flash memory (where the main program is stored), a Marvell AP102 SoC (presumably containing the main CPU inside) and a PS1080-A2 DSP (to process the image coming from the cameras), among others. All of this is fitted on three different boards stacked together [56].

The sensor is operated through the use of Microsoft’s opaque APIs, which in turn communicates to super-secret software installed on both the Kinect and the Xbox 360’s Operating System. The Kinect uses a USB 2.0 A connection to plug into the console. The ‘Slim’ re-design of the Xbox 360 released in the same year was also branded ‘Kinect compatible’ as it could supply power to the bar as well (with the provision of an extra proprietary port on the back of the console), older models require a separate power brick for the Kinect.

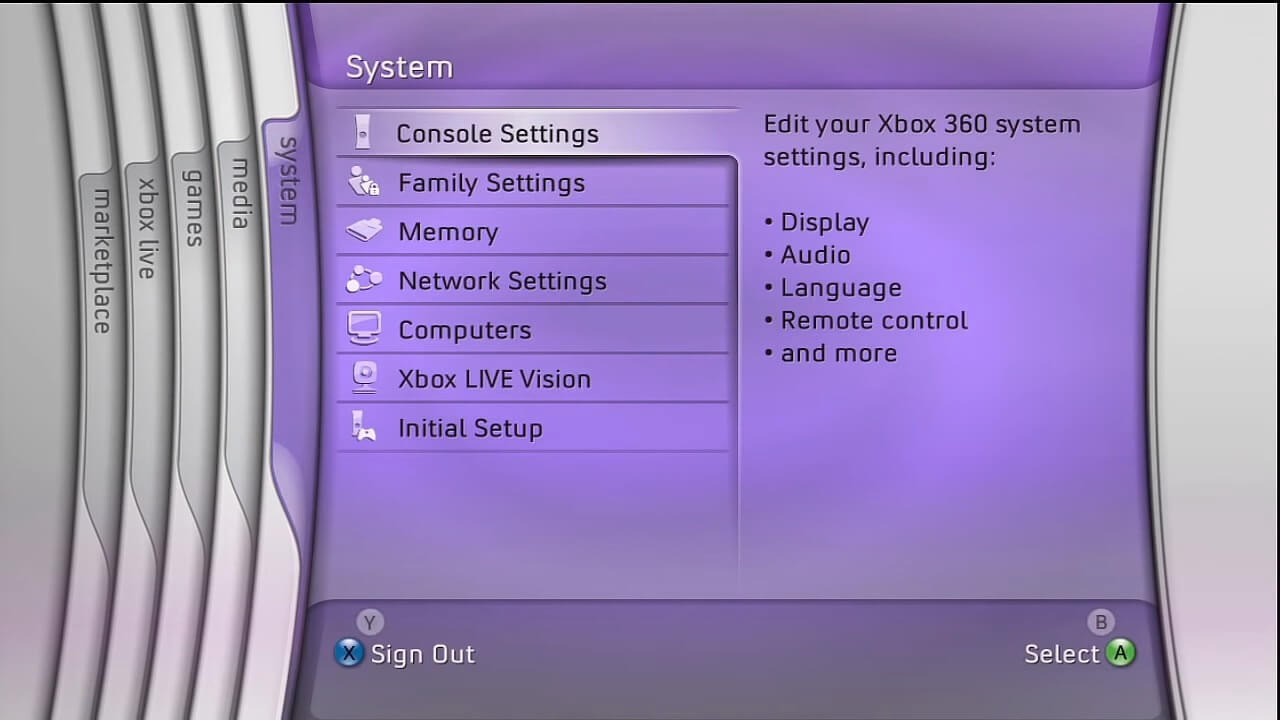

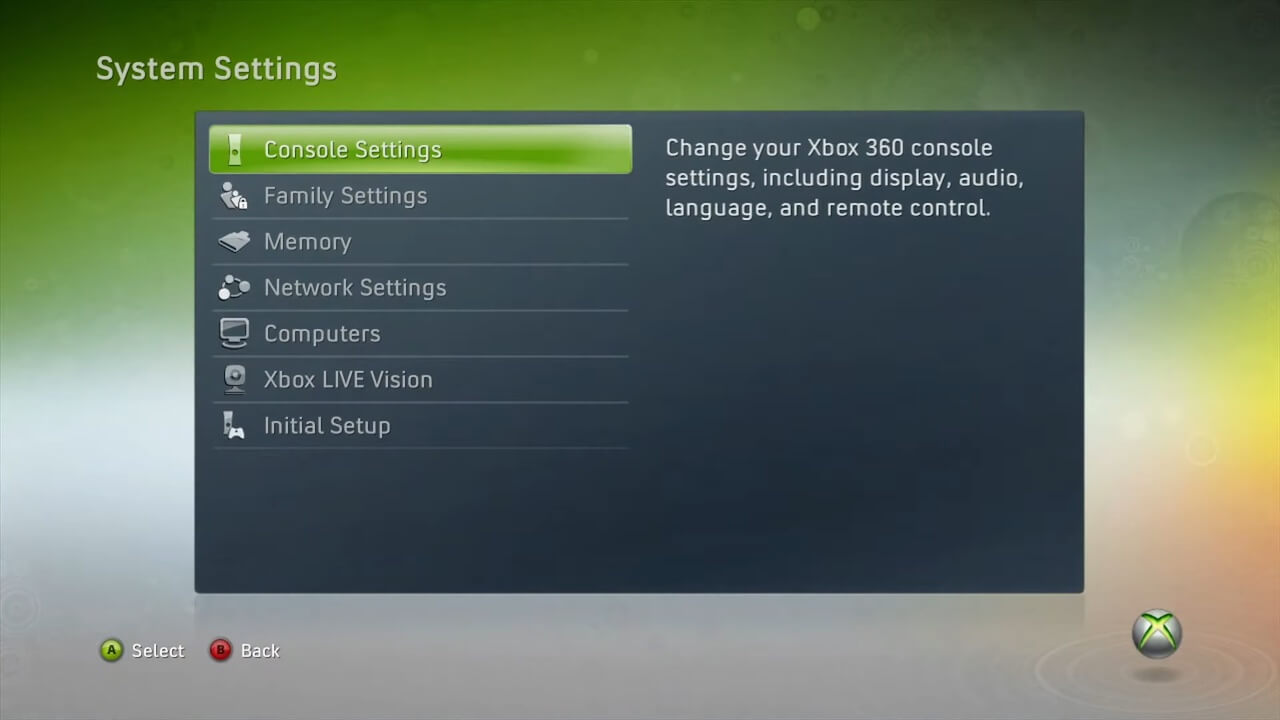

Operating System

The Xbox 360 was subject to the same needs and fashions that the PlayStation 3 went through. So the former offers many services, including online gaming (through Xbox Live), a digital marketplace, media player, file system explorer (albeit extremely simple) and other utilities.

Overview

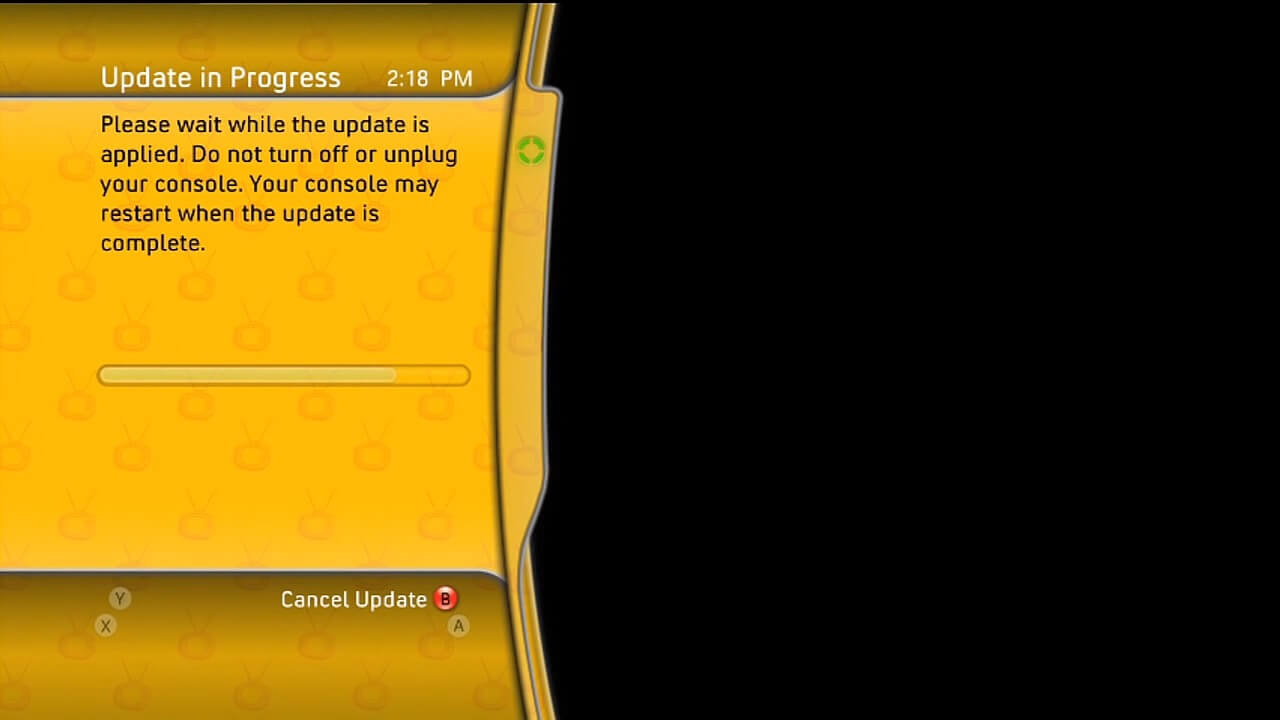

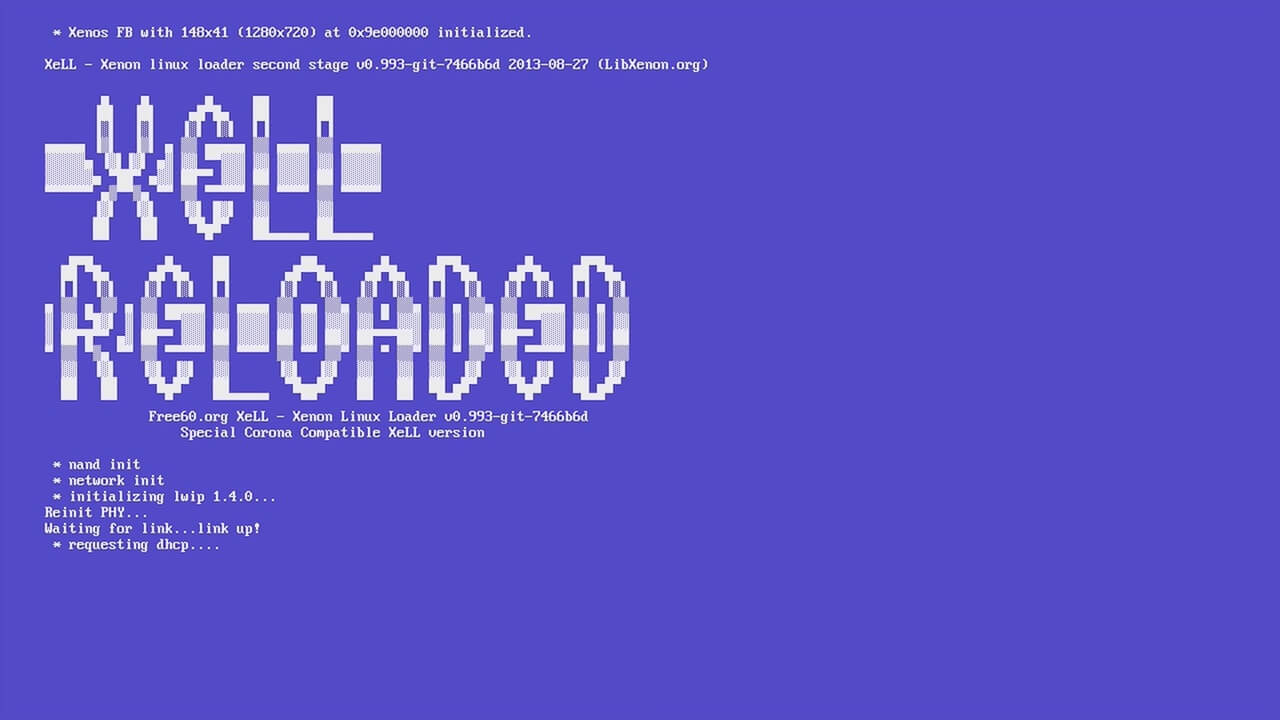

The Operating System of the Xbox 360 is a collection of bare-metal utilities and userland applications tightly squashed together to fit into 16 MB of NAND. Just like the PlayStation 3, Microsoft built their OS to provide multimedia and networking (i.e. multi-player) capabilities, plus the ability to play games and secure the system from external intrusion.

That being said, the system contains a few core components that take care of the low-level area of this console (hardware access, security and resource management). The rest is composed of applications (i.e. the splash animation, the interactive shell called ‘Dashboard’ and the game itself) and user data (i.e. game saves, user profile, network settings).

A tumultuous progress

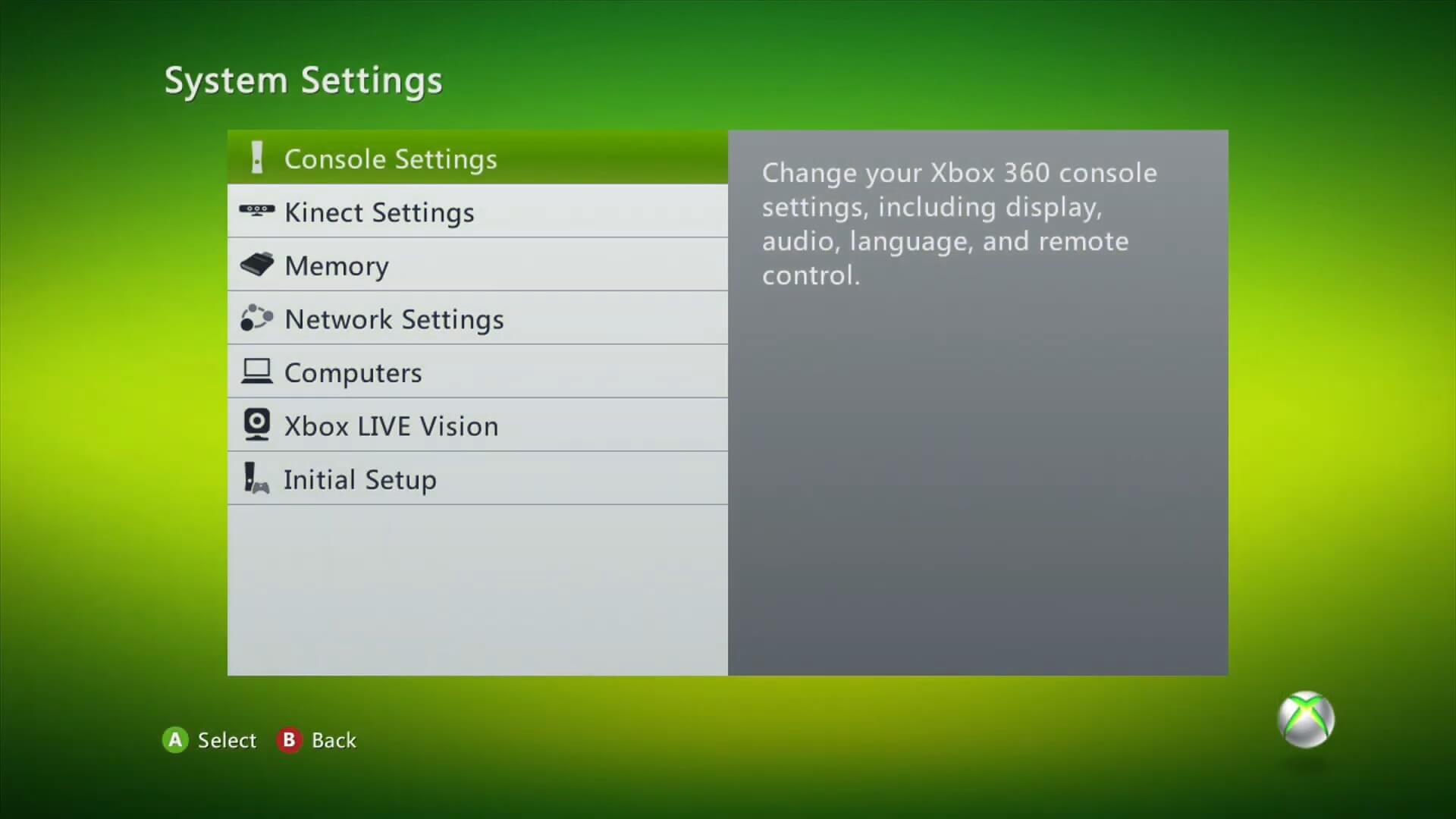

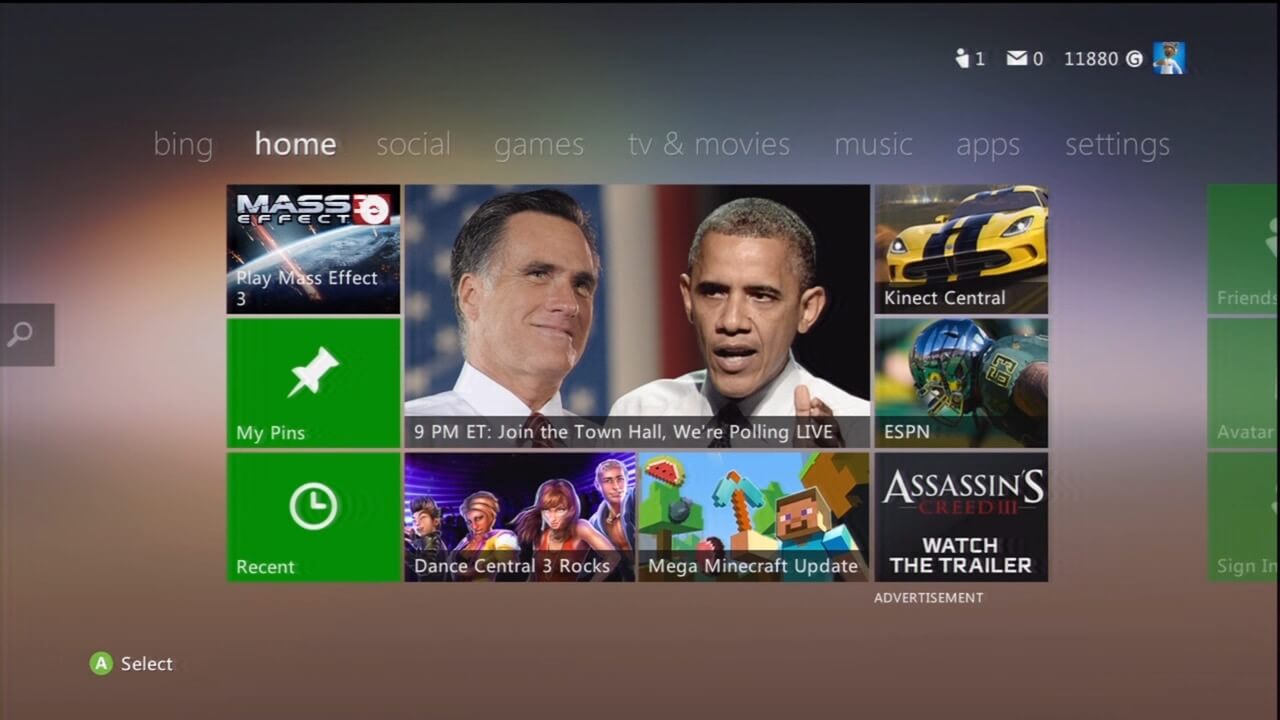

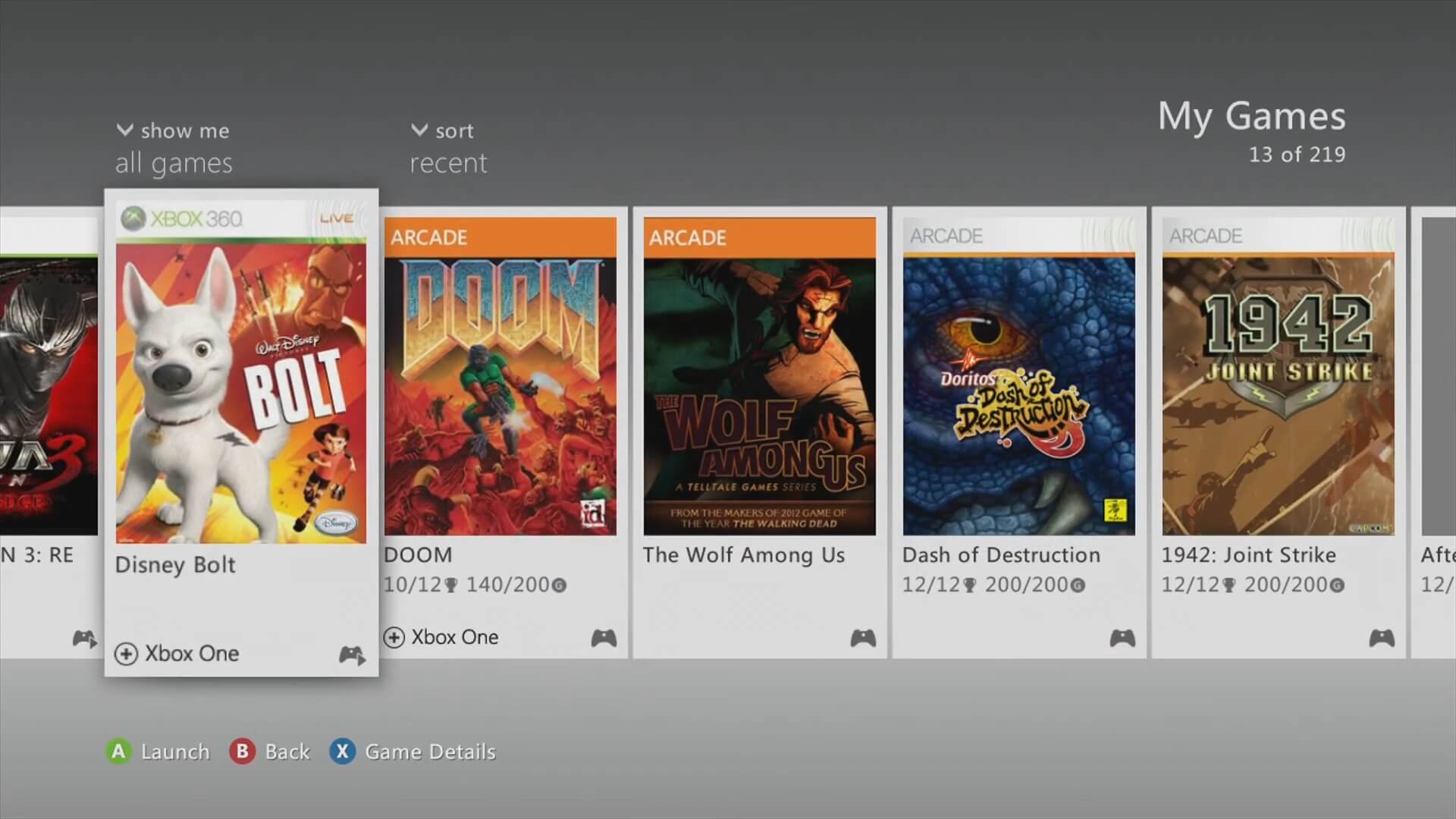

Throughout the life of this console, I noticed a more chaotic evolution than its competitor, which involved constant re-branding and radical redesigns of the user interface. I presume Microsoft was trying to shift from one target audience to another. So, to understand this section better, I’ve organised its evolution into these periods:

- The multimedia hub era (2005-2008): as the first home console to debut in the 7th generation, high-definition graphics, Xbox Live (online platform) and HD movies were the main selling points. And in the case you got bored with them, you could resort to buying accessories [57] (i.e. the remote controller, the headset, the HD DVD reader) to ‘enhance’ your experience.

- The competitive era (2008-2011): with the PlayStation 3 and the Wii now occupying store space, Microsoft found itself in need to aggressively compete for the consumer’s attention. First, a new system update called ‘New Xbox Experience’ overhauled the old interface to increase user personalisation (i.e. 3D avatars) and enhance the social aspect of this console. Meanwhile, a new ‘killer app’ lands in the form of a physical accessory: Kinect. Nobody knows its outcome, yet it proves a very engaging topic of conversation.

- The cloud era (2011-2013): as all the previous enthusiasm slowly dissipates, Microsoft simplified its user interface to align with its other platforms (Windows 8 and Windows Phone 7) and provided users with the chance to move their local data to the cloud (a.k.a Microsoft’s servers). In the process, third-party advertising became more prominent in the user interface (possibly to increase their source of income). Nonetheless, users are now expecting the successor of the Xbox 360.

- The capitulation (2014 onwards): with the new successor (Xbox One) reaching the stores, Microsoft dedicated minimum efforts to their (now old) console. Users will only receive system updates in the form of bug fixes.

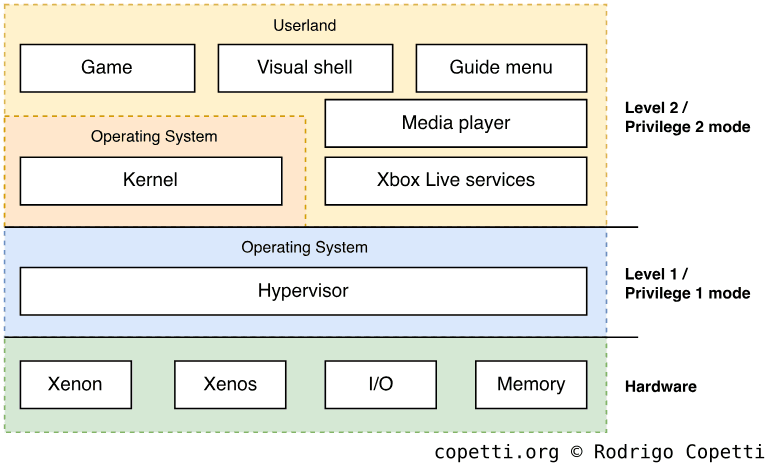

A recallable security design

If you recall my deconstruction of the PlayStation 3’s operating system, the latter was divided into three areas:

- The Hypervisor, which has complete control of the hardware.

- The Kernel, interfacing user programs (mostly games) with the hypervisor, and in doing so it provides an extra layer of protection.

- The user space, encompassing all programs executing on top of the kernel, including games and other apps (i.e. the shell and media player).

This design is correlated to the PPU’s privilege levels (affecting both Cell and Xenon) which prevents ‘casual’ applications, like games, from accessing sensitive resources, such as decryption keys.

IBM enacted three privileges (instead of just two) to allow multiple operating systems running at the same time. With this idea, each OS would only live under the two lowest levels while the highest level would be reserved for the program supervising all operating systems. In practice, the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 only require a single operating system (except for OtherOS, but that was quickly scrapped). Consequently, Sony and Microsoft designed a hypervisor that enforces their respective security model and performs memory management tasks. Conversely, the architectural differences between Cell and Xenon led to very distinct implementations of hypervisors, so each is subject to unique flaws and strengths.

The most notable difference between the security model of the Xbox 360 and the PlayStation 3, is that the former runs both the Kernel and user-space programs under the same privilege mode (the second level) [58]. So, all critical tasks rest within Hypervisor, which enjoys extra acceleration from the hardware side (I’ll explain more about it in the ‘Anti-piracy’ section).

Architecture

Let’s take a deep dive at the operating system’s main components, note this doesn’t include the boot loaders, but for that, I’ve dedicated a separate section. For now, we’ll check the components that reside in memory after the console boots up.

The Hypervisor

The Hypervisor is an incredibly small program that only occupies 128 KB [59]. Furthermore, by being assigned the highest privilege level available, it’s tasked with:

- Preventing programs from accessing areas beyond the permitted boundaries.

- Combined with the use of page tables, it restricts which areas of memory can be executed by the CPU. This technique is called Write Xor Execute or ‘W^X’.

- Encrypting executable code.

- Refusing to load executables that aren’t signed by Microsoft.

- Protecting memory data from being tampered with. This is done by encrypting the data in main RAM and decrypting it just after the CPU fetches it from L2 cache.

- This is a complex but interesting feature which is explained further in the ‘Anti-piracy’ section.

The hypervisor is operated through the use of ‘system calls’ [60], external programs invoke these to request functions from the hypervisor. Though whether the hypervisor complies or not is a matter of the program’s accreditations.

The Kernel

Since the Hypervisor focuses on bare-metal services, an extra layer of abstraction is added in the form of a Kernel. The latter also resides in memory but gets assigned a lower privilege level. The main job of the Kernel is to expose routines that userland programs can benefit from, for instance:

- Device drivers: in essence, I/O is interfaced by the Kernel so programs are not hard-coded to specific hardware (resulting in platform-dependent code), which would prevent old games from working on late Xbox 360 revisions.

- File system management: a file system defines how data is organised in a physical medium, the Xbox 360 supports many types of media and the Kernel implements various file systems for each one. This enables programs to manipulate persistent storage using files and directories and not raw sectors.

- Bootstrapping core applications: once the Kernel is up and running, it makes sure that the user interface and other executables are running, allowing the user to interact with the console.

- Thread scheduling: remember the previous paragraph about programming styles? Well, the thread scheduler is found here. Furthermore, the scheduler implements preemptive multitasking as its method for alternating between threads and avoiding jams.

- To balance performance across all running services, the scheduler applies some constraints. For instance, the fourth hardware thread is reserved for the audio pipeline and software downloads; and the second hardware thread is prioritised for concurrent file system operations.

To work, the kernel reserves 32 MB from main RAM to allocate all of its resources.

The User land

Userland programs encompass any executable running on top of the kernel. These are found in the form of a special container called Xbox EXecutable or ‘XEX’ [61]; and follow a similar structure to the traditional EXE container used by Windows - albeit tailored to the specifications of the Xbox 360. The most important difference is that XEX’s executable code follows the PowerPC ISA binary structure (instead of x86) and it must be encrypted to run (the code is signed with Microsoft’s private keys and the headers/meta-data store a hash to prevent tampering).

From the boot animation to the game itself, everything is a distinct XEX file. Some are automatically loaded by the Kernel (the boot animation and the interactive shell) and others by the user (the game, the media player, etc) using the shell. When the user or the Kernel request to run a XEX, the Kernel copies it to main memory and the Hypervisor checks its signature, re-encrypts it, marks the area as ‘executable’ and finally instructs the CPU to run it [62].

While this console doesn’t provide any fancy multitasking between games (which is not a priority for a console, in my opinion), the Kernel still takes the aforementioned 32 MB of main RAM as its working area. This is what makes it possible to open the Xbox Guide (that popup menu that shows up after pressing the ‘Xbox logo’ button on the controller) and/or play music mid-game. To switch between full-screen applications, the Xbox Guide contains an entry to return to the dashboard (loading it up again) so the user can select another program.

Finally, all user data is grouped into a virtual Profile. Thus, the Kernel runs another program called ‘XAM’ which provides profile-related services (achievements tracking, avatar selector, save data storage) [63]. A new profile is set up upon powering the console for the first time and there can be more than one profile stored.

Backwards compatibility

As a compelling side note, the Xbox 360 can run a considerable subset of games belonging to the previous Xbox (to avoid confusion, let’s call it the ‘classic’ one). This was done through pure and hard software emulation and, while it didn’t provide the same degree of compatibility of the CECHA PS3 revision, I believe the methods were more clever, cost-effective and consistent.