Supporting imagery

Model

Released on 21/04/1989 in Japan, 31/07/1989 in America and 28/09/1990 in Europe.

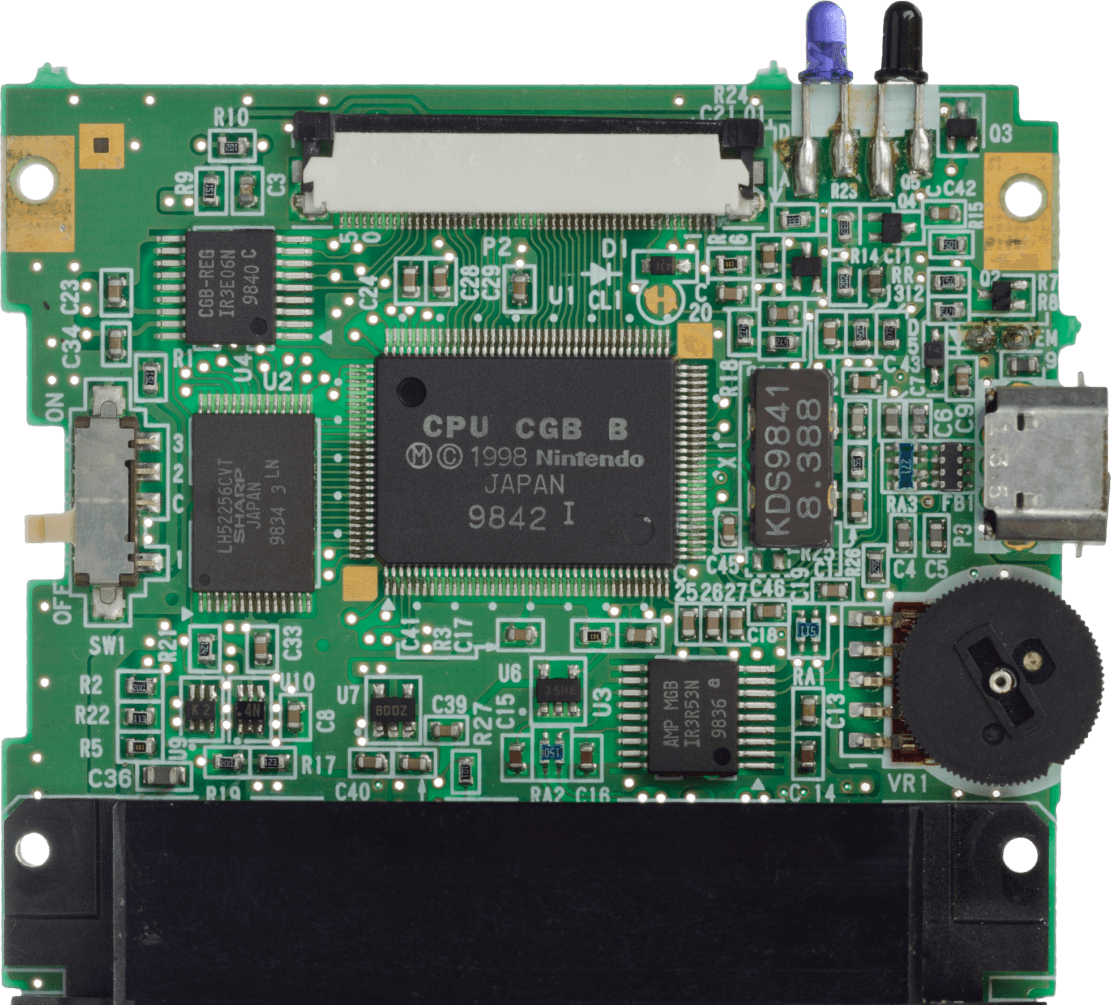

Released on 21/10/1998 in Japan, 18/11/1998 in North America, 23/11/1998 in Europe.

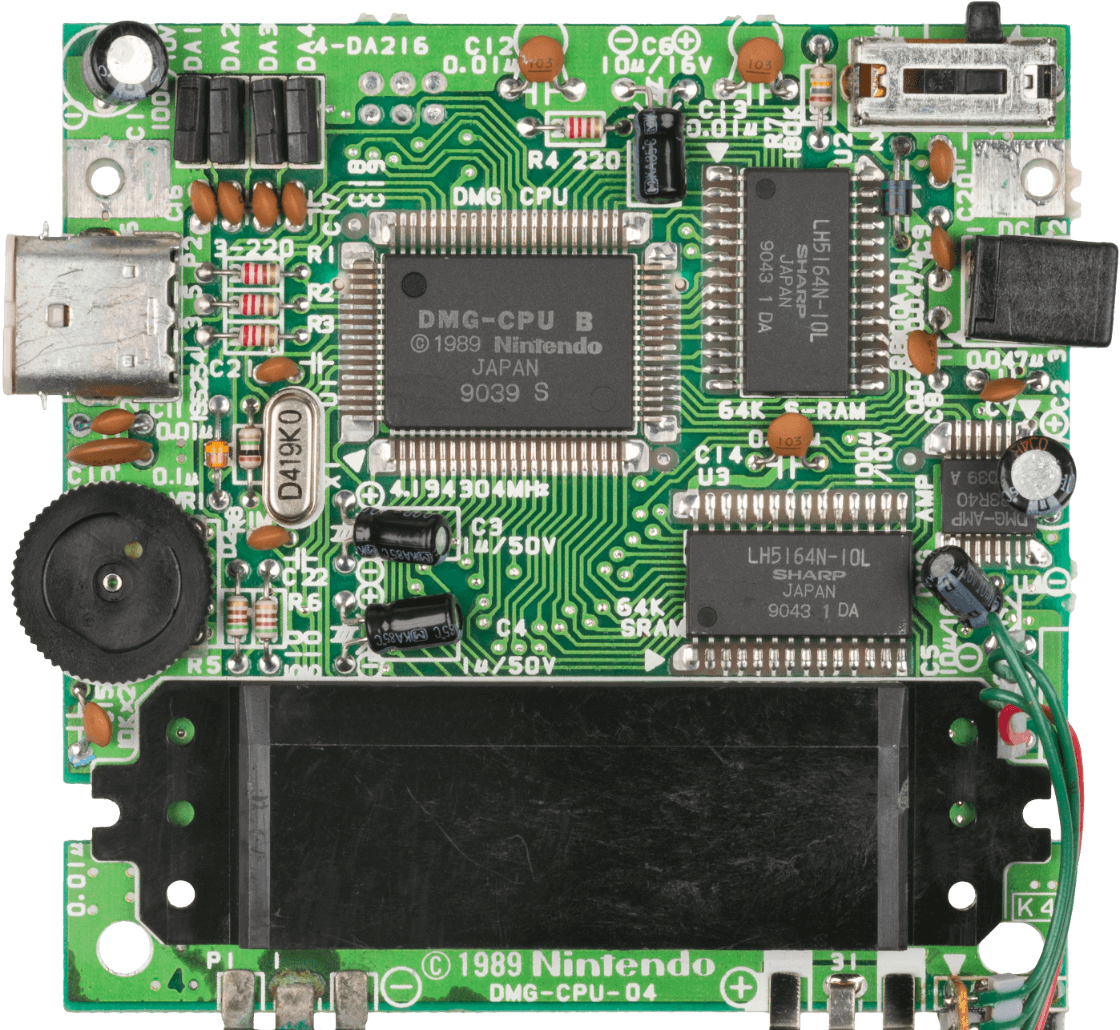

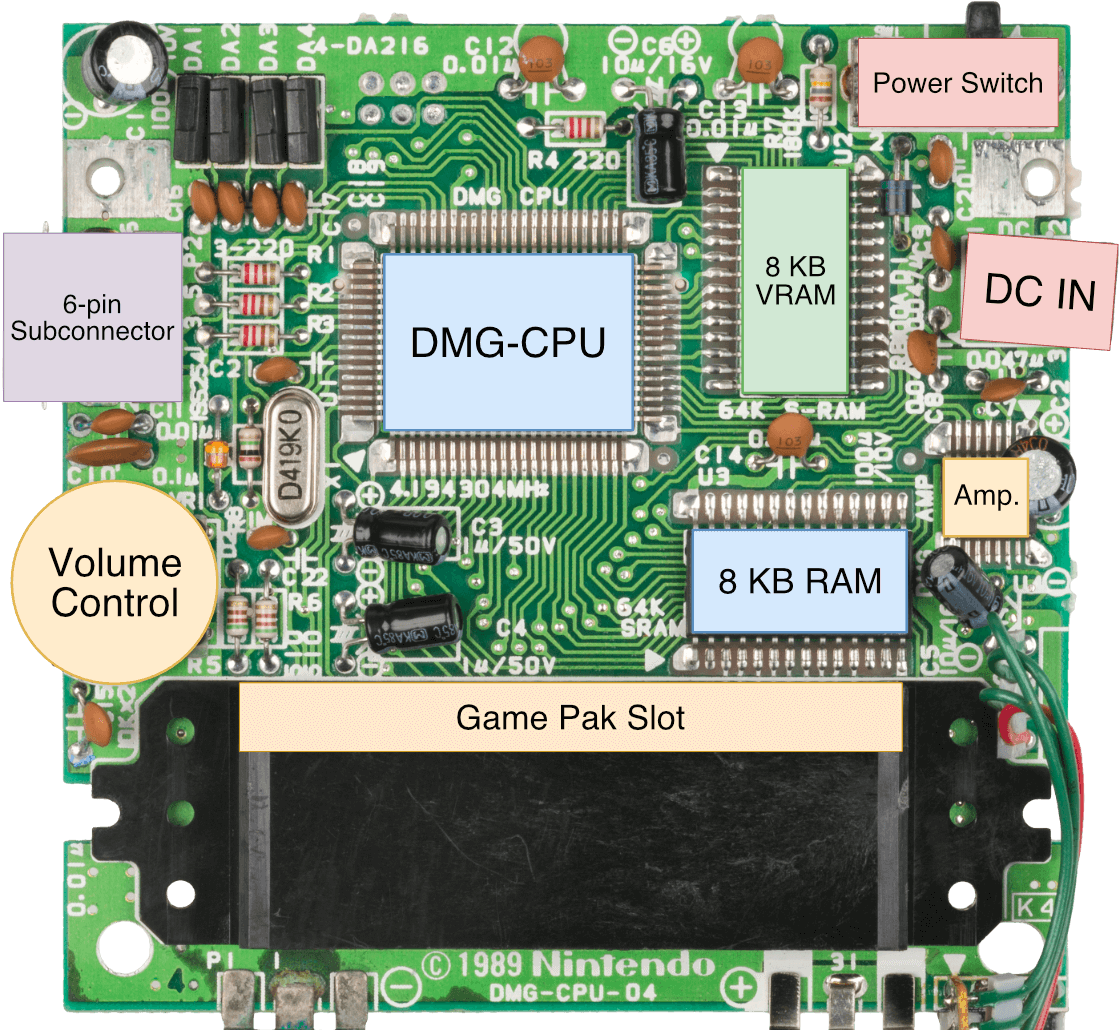

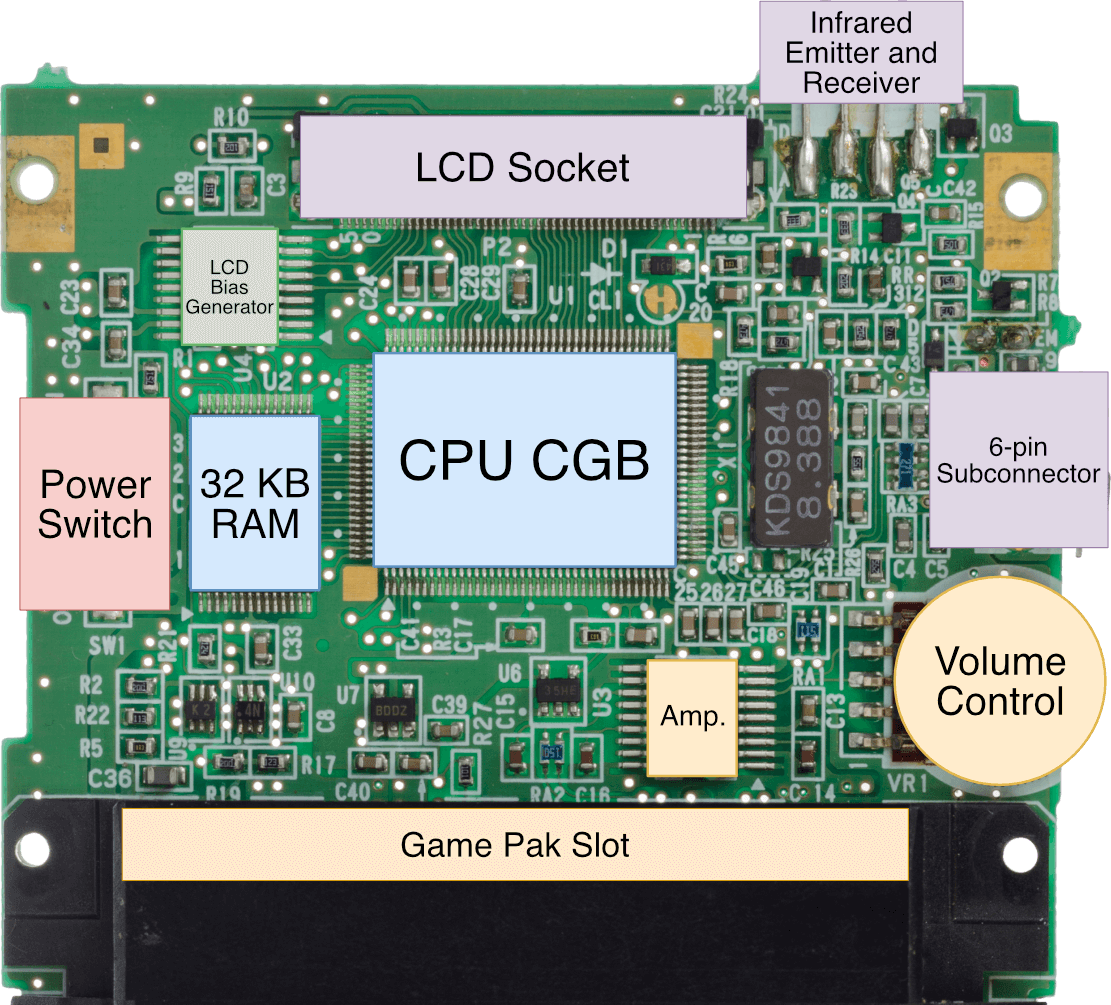

Motherboard

Showing revision '04'. Note that 'DMG' is the identifier of the original Game Boy model.

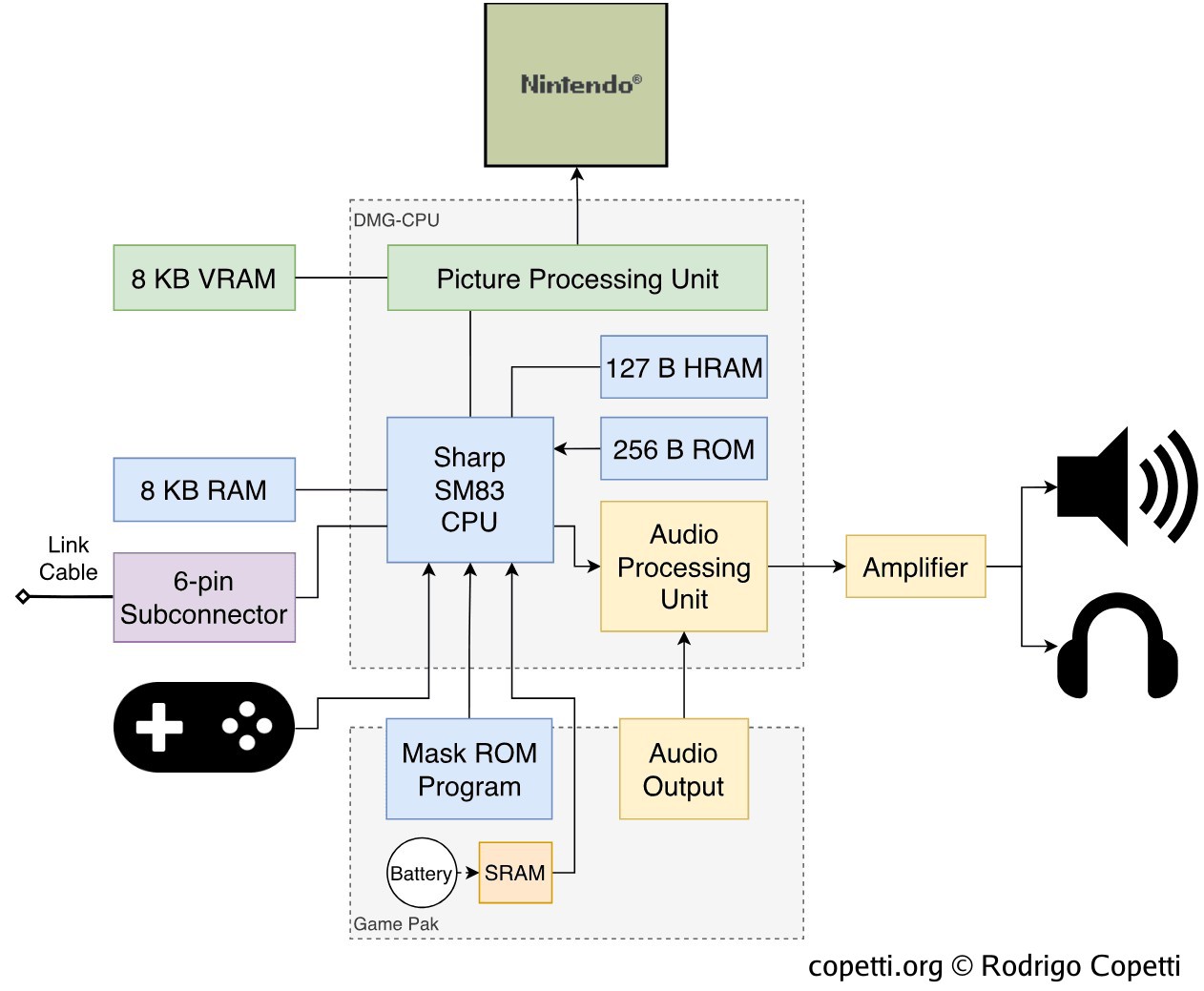

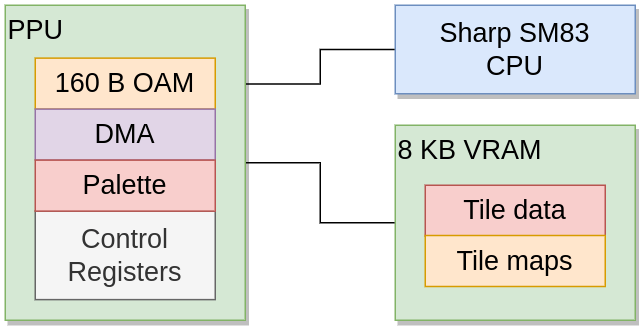

Diagram

Based on the original Game Boy.

A quick introduction

The Game Boy series can be imagined as a portable version of the NES with limited power, but you’ll see that it included very interesting new functionality.

The rainbow analysis

The immense popularity of this console resulted in a variety of revisions (i.e. Game Boy Pocket, Light, and even in the form of Super Nintendo cartridges). As a matter of fact, the Game Boy brand covers two generations. Within the 4th generation we find the monochrome Game Boy and its revisions, and in the next generation resides the Game Boy Color (shipped after the demise of the Virtual Boy). The good news is that this article covers both ends. So, in the end, you’ll get a good understanding of how the Game Boy works and how its technology subsequently evolved to become the Game Boy Color.

CPU

Instead of placing many off-the-shelf chips on the motherboard, Nintendo opted for a single-chip design to house (and hide) most of the components, including the CPU. This type of chip is called System On a Chip (SoC) and, in this case, it’s been specifically crafted for this console, enabling Nintendo to tailor it to their needs (power efficiency, anti-piracy and extra I/O, among other things). At the same time, this chip can’t be found in any retail catalog, meaning competitors back then had a harder time cloning it.

That being said, the SoC found on the Game Boy is referred to as DMG-CPU or Sharp LR35902 [1] and, as the name indicates, it’s manufactured by Sharp Corporation. This company, along with Ricoh (the NES’ CPU supplier), enjoyed a close relationship with Nintendo.

The CPU core

Within DMG-CPU, the main processor is a Sharp SM83 [2] and it’s a mix between the Z80 (the same CPU used on the Sega Master System) and the Intel 8080. It runs at ~4.19 MHz, which is faster than the average 1-MHz CPU, but remember clock speeds can be deceiving.

Now, back when I did the analysis of the Master system, I explained the Z80 is itself a superset of the 8080. So, what does the SM83 actually have and lack from those two? [3]

- Neither the Z80’s

IXorIYregisters nor the 8080’sINorOUTinstructions are included. This means that I/O ports are not available. I’m not certain if that’s just a measure to reduce costs, but one thing for sure is that components will have to be completely memory-mapped [4]. - Only Intel 8080’s set of registers are implemented. Consequently, there are only seven general-purpose registers, unlike the Z80 with its 14 registers (due to the addition of an ‘alternative’ set).

- Includes some of the Z80’s extended instruction set (only bit manipulation instructions).

Furthermore, Sharp also added a few new instructions that are not present in either Z80 or 8080. They optimise certain operations related to the way Nintendo/Sharp arranged the hardware. One example is the new LDH instruction (meaning ‘load from high memory’ [5]), which has been specifically included to operate on the last 256 bytes of the memory map (where addresses start at $ff00) and, most importantly, fits in one fewer byte (and is thus slightly faster).

The Color effect

Almost 10 years later, after the abandonment of the Virtual Boy and its cutting-edge hardware, a humble successor arrived: the Game Boy Color. Inside it, there’s a new SoC named CPU CGB that carries a few additions. However, its SM83 CPU core remains the same, except for its doubled clock speed (now running at ~8.38 MHz).

It’s hard to think that after a decade Nintendo would still bundle the same CPU, but such a decision does come with the following advantages:

- Developers can re-use their acquired skills to program the new console.

- There’s a cost saving by not having to re-design their system to work for a new architecture.

- Backwards compatibility becomes possible without considerable effort. In fact, Nintendo implemented it by programming two modes of operation on CPU CGB:

- Normal mode: The SM83 operates at ~4.19 MHz.

- Dual-speed mode: The SM83 operates at ~8.38 MHz.

Albeit, this comes at the cost of adopting outdated technology by late-90s standards. You only have to look at the state of the CPU market to notice the capabilities Nintendo was missing out (to be fair, Nintendo did try with the Virtual Boy).

Hardware access

The SM83 maintains an 8-bit data bus and a 16-bit address bus, so up to 64 KB of memory can be addressed. The memory map is mainly composed of the following endpoints [7]:

- Game Pak (the game cartridge) space.

- Work RAM (WRAM), High RAM (HRAM) and Display RAM (VRAM).

- I/O (joypad, audio, graphics and LCD).

- Interrupt controls.

These will be explained throughout this article.

Memory available

Nintendo fitted 8 KB of RAM on the motherboard, this is for general purpose use (which they call Work RAM or ‘WRAM’) [8]. Notice that this is four times larger than what the NES included.

There’s an additional 127 B of RAM housed in the SoC. It is called High RAM or ‘HRAM’, and provides a small space for data that can be accessed faster via the SM83’s unique LDH instruction. This is very similar to the 6502’s ‘Zero Page’ mode [9], which also optimised performance based on the memory location. Now, High RAM is not technically faster to access than general RAM, but it’s an area prioritised for the CPU. You’ll see what this means when you reach the ‘Graphics’ section, where I discuss the DMA component.

Later on, with the Color variant, Nintendo enlarged WRAM to 32 KB. However, since the CPU remained unchanged (particularly its addressing capabilities), it’s not possible to connect all the new memory without first overflowing the available address space. To tackle this, Nintendo’s engineers implemented bank switching. Originally found in NES cartridges, the Game Boy Color uses the same principle to access those 32 KB only using 8 KB of memory space. The trick is simple: the last 4 KB can be swapped using seven different banks. Consequently, the CPU bundles an extra register (called SVBK) acting as the bank switcher, this is what developers must use to examine the extended memory.

Graphics

All graphics calculations are done by the CPU, and then the Picture Processing Unit or ‘PPU’ renders them. This is another component found inside DMG-CPU and could be described as an improved version of the predecessor’s graphics chip (of the same name).

The picture is displayed on an integrated LCD screen, it has a resolution of 160×144 pixels and, in the case of the monochrome Game Boy, shows 4 shades of grey (white, light grey, dark grey and black). Since the original Game Boy has a green LCD, the picture will look greenish.

If you’ve read the NES article before, you may remember that the PPU was designed to follow the CRT beam. However (and for obvious reasons), we got an LCD screen in the Game Boy. Well, the new PPU also follows that methodology as LCDs require to be refreshed too. In doing so, this console will enjoy CRT-based effects that previously enabled NES developers to come up with imaginative content.

Organising the content

The PPU is connected to 8 KB of VRAM or ‘Display RAM’. In doing so, it also provides arbitrated access to the CPU. Those 8 KB will contain most of the data the PPU will need to render graphics. The remaining materials will instead be stored inside the PPU, as they require faster access rates.

The game is in charge of populating the different areas with the correct type of data. Moreover, the PPU exposes registers so the game can instruct the PPU on how that data is organised. Nevertheless, there are many rules to follow (you’ll see it in the following sections).

Constructing the frame

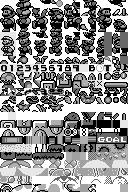

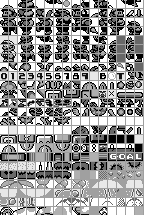

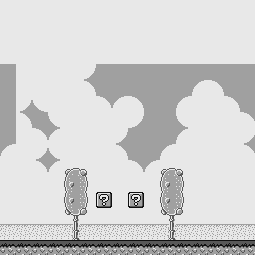

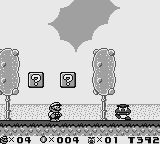

Let’s see how the PPU manages to draw stuff on the screen. For demonstration purposes, Super Mario Land 2 will be used as an example.

Tiles

The PPU uses tiles as a basic ingredient for rendering graphics, specifically, sprites and backgrounds [10].

Tiles are just 8x8 bitmaps stored in VRAM in a region called Tile set or ‘Tile pattern table’, each pixel corresponds to one of the four shades of grey available. In practice, however, the shades of grey are selected through a ‘colour’ palette. The monochrome Game Boys contain registers that define these palettes. As explained before, there’re only four colours/shades of greys to choose from, so a single 8-bit register can fit a palette of four shades without issue. That being said, the system provides three registers (thus, three programmable palettes) with restricted use (more about this explained later).

Furthermore, tiles are grouped into two pattern tables.

To build the picture, tiles are referenced in another type of table called a Tile map. This information will tell the PPU where to render the tiles. Two maps are stored to construct different layers of the frame.

The next sections explain how tile maps are used to construct the layers.

Background Layer

The Background layer is a 256x256 pixel (32x32 tiles) map containing static tiles. However, remember that only 160x144 is viewable on the screen, so the game decides which part is selected for display. Games can also move the viewable area during gameplay, that’s how the Scrolling Effect is accomplished.

One of the two tile maps can be used to build the background layer. Also, there’s only one palette available for this layer.

Window

The Window is a 160x144 pixel layer containing tiles displayed on top of the background and sprites. This layer doesn’t scroll.

The remaining tile map can be assigned to the Window layer, it also shares the same palette with the Background layer.

All in all, this may sound like a silly feature. Since the Window has no transparency and thus completely obscures the Background, you may wonder ‘What is it useful for?’. Well, both Background and Window can be used concurrently at different parts of the screen. This is intended for displaying information chiefly at the bottom of the screen, but whereas on the NES this required performing complex and timed writes, the Game Boy’s PPU can automatically handle it.

Thus, games normally use it to display player stats, scores and other ‘always-on’ information.

Sprites

Sprites are tiles that can move independently around the screen. They can also overlap each other and appear behind the background, the viewable graphic will be decided based on a priority attribute.

This layer also has an extra colour available/required: Transparent. Initially, this means they can only display three different greys instead of four. Luckily, this layer in particular is provided with two dedicated palettes to choose from.

The Object Attribute Memory or ‘OAM’ is a map stored inside the PPU that specifies the tiles that will be used as sprites. Instead of using a tile map, sprites are defined in OAM. Games typically fill this region by calling the OAM DMA unit found inside the chip, the DMA fetches data from main RAM or game ROM and sends it to OAM. Now, whilst DMA is at work, the CPU can’t access external memory (hence the importance of using HRAM during that period).

Apart from the tile index, each entry contains the following attributes: X-Y position, chosen palette, priority and flip flags (allowing to rotate the tile vertically and horizontally).

The PPU is limited to rendering up to ten sprites per scan-line and up to 40 per frame, overflowing this will result in sprites not being drawn.

Result

Once the frame is finished, it’s time to move on to the next one! However, the CPU can’t modify the tables while the PPU is reading from VRAM, so the system provides a set of interrupts triggered when the PPU is idle. You can recall this behaviour from the times of the NES.

When a single scan line is complete, the Horizontal Blank period starts. This allows to fiddle with the part of the frame that has not yet been drawn.

When all scan lines are complete, the Vertical Blank period starts, and a dedicated interrupt is called. The game can now update the graphics for the next frame.

There’s an extra state called OAM search that is triggered at the start of the scan-line, at this point the PPU is processing which sprites will be displayed in that scan-line, so the game can update any region except OAM.

Secrets and Limitations

The inclusion of the Window layer and extra interrupts allowed for new types of content and effects.

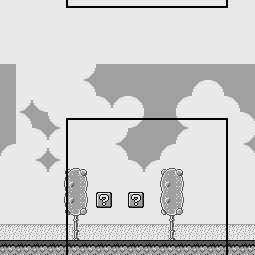

Wobble effect

Horizontal interrupts allowed to alter the frame before being finished. This means that a different scrolling value could be applied at each line, resulting in each row of the frame being shifted at different paces.

This achieved an interesting Wobbling effect (I’m not sure that’s the official name of it).

The Color additions

The Game Boy Color’s PPU behaves as a superset of the original. You will see now what are the additions of the so-called ‘Color’ model of this brand.

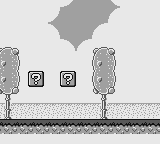

Modes of operation

A hybrid Game Boy Color game running in CGB mode.

To begin with, for compatibility reasons, the new PPU has two modes of operation. Yet, Nintendo wanted Color users to see enhancements even with the monochrome-only games. Consequently, the two modes of operation are as follows:

- CGB mode: Extended PPU mode with all the visual improvements that comprise the new Game Boy Color games.

- DMG mode: Traditional mode with all the extras disabled. However, you’ll see in the ‘Operating System’ section that monochrome games are nonetheless enhanced with colour palettes.

Organising the (new) content

The CGB motherboard now houses 16 KB of VRAM instead, which is double the original VRAM amount. Due to the CPU’s addressing limitations, this new arrangement is implemented in the form of two 8 KB banks, with a new register (called VBK) acting as a switcher. On the other side, the PPU can access the two banks at the same time. At the end of the day, this means programmers only need to fill the VRAM banks with the help of VBK, and then specify in the tile map the bank where the tile is found, so the PPU can take care of the rest.

That being said, what can you do with the extra VRAM? Many things:

- Store twice as many tiles.

- Store more palettes, which offer a wider colour gamut as well.

- Extend the tile metadata space to encode more effects and address extra palettes.

The visuals

Thanks to the new PPU, programmers can now define colour palettes with 32,768 colors to choose from.

Firstly, developers must now populate a new area called Palette Memory, which stores up to sixteen colour palettes (half for the Background and Window, half for sprites) that encode four colours [11]. Each entry fits in a 16-bit value (2 bytes) and only 15 bits are used. Palette Memory is not addressed by the CPU, however, a new register is used as a buffer to write over this memory (a methodology found in the Super Nintendo). Overall, that’s how the CPU defines palettes.

Having said that, Background and Window tiles can reference any of those eight palettes. The same happens with Sprite tiles, except they are constrained to three-colour palettes, as one entry is reserved for the ‘transparent’ colour.

The extra space

Moving on, Tile sets are now twice as big. Thus, programmers can store double the amount of tiles in VRAM. Background/Window Tile maps have been extended as well, resulting in extra meta-data being encoded. Consequently, expanding the capabilities of these layers. For instance, their tiles can now be horizontally and vertically flipped, saving the game from storing duplicated graphics in VRAM (which, in turn, can be exploited to draw more unique content).

Furthermore, CPU CGB also bundles one extra DMA unit, which can copy the contents of the Game Pak or WRAM to VRAM. It operates in two modes [12]:

- General-purpose DMA: The transfer will happen at any time and the DMA will get priority over any other memory access. So, programmers need to be careful about when to use this component (i.e. during or outside scanning) and how (the amount of data to copy), as misuse can lead to screen tearing (VRAM access will be blocked during the transfer).

- Horizontal Blank (H-Blank) DMA: The transfer will only happen during H-Blank periods. This avoids screen artifacts, but can only transfer content in batches of 16 Bytes, and pauses during LCD scanning.

Once more, this unit offers programmers new possibilities to provide richer content, as it takes advantage of periods originally left for idling.

Audio

The audio system is carried out by the Audio Processing Unit (APU), a PSG chip with four channels [13].

Curiously enough, this is one of the few sections that hasn’t evolved between models. In fact, it can’t even be sped up, since if you change the speed of the oscillators, you won’t hear ‘better’ sounds, but a higher pitch.

Functionality

Each of the four channels is reserved for a single type of waveform:

Pulse

Pulse waves have a very distinct beep sound that is mainly used for melody or sound effects.

The APU reserves two channels for one pulse wave each. These use one of four different tones constructed by varying their pulse width. The first channel has an exclusive Sweep control available.

Due to the limited number of channels, the melody will often be interrupted when effects have to be played as part of the gameplay. This is very noticeable in games like Pokemon Red/Blue when, during a battle, the Pokemon’s cry will overlap all the channels used for music; this is also why no Pokémon battle music uses percussion.

Wave

The APU allows defining a custom waveform to be heard from its third channel. The wave is composed of 32 4-bit samples which are stored in a wavetable.

This channel also allows controlling its frequency (enabling it to produce different musical notes from the same entry) and volume.

Noise

Noise is basically a set of random waveforms that sound like white static. One channel is allocated for it.

Games use it for percussion or ambient effects.

This channel has only 2 tones available to use, one produces clean static and the other produces robotic static. Its frequency can also be controlled.

Secrets and Limitations

The mixer outputs stereo sound, so the channels can be assigned to the left side or on the right one, this is only possible to hear from the headphones though! The speaker is mono.

Furthermore, the mixer chip is also connected to a dedicated pin on the cartridge, allowing it to stream an extra channel with the condition that the cartridge outputs the analogue sound (only possible with extra hardware). Nevertheless, no game in the market ended up using this feature, and you won’t find this pin on the Game Boy Advance’s backwards compatible subsystem either.

Operating System

Unlike the NES, which booted straight into the game, the Game Boy was designed to always boot from an internal 256 Byte ROM, and only then jump into the game code. The boot process is as follows [14]:

- After the console is switched on, the CPU starts reading at address 0x0000 (Game Boy’s ROM location).

- RAM and APU are initialised.

- The Nintendo logo is copied from the cartridge ROM to Display RAM, and then it’s drawn at the top edge of the screen. If there is no cartridge inserted, the logo will contain garbage tiles. The same may happen if it’s improperly inserted.

- The logo is scrolled down and the famous po-ling sound is played.

- The game’s Nintendo logo is matched against the one stored in the console’s ROM. Afterwards, a quick checksum is done on the cartridge’s ROM header to make sure the cartridge is correctly inserted. If any of these checks fail, the console freezes.

- The console’s ROM is removed from the memory map.

- CPU starts executing the game.

Interestingly enough, the Nintendo logo displayed on the screen is not cleared from VRAM, so games can apply some animation and effects to introduce their own logo.

The revised sequence

Once again, in the case of the Game Boy Color, we find drastic changes in the contents of the ROM. For instance, the size of the ROM is now 2 KB [15] and the routines exhibit new behaviour:

- The boot sequence will now check if it’s got a Game Boy-only or Game Boy Color game inserted, and then set the corresponding registers to activate DMG or CGB mode. The boot code checks for specific game metadata (within the cartridge’s ROM) that is structured differently for CGB games.

- In the case a DMG game is inserted, the boot program will also fill Palette RAM with calculated palettes, these are based on a simple but clever algorithm that also relies on the game’s metadata. This is what makes monochrome games look coloured when running on the next-gen console.

- At this stage, the user may press a button combination that will alter the boot code’s palette of choice.

- The Nintendo logo check now makes use of HRAM as well (to no avail, however).

Games

Games are written in assembly and they have a maximum size of 32 KB, this is due to the limited address space available. However, with the use of a Memory Bank Controller (mapper), games can reach bigger sizes. The biggest Game Pak (cartridge) found in the market has a 1 MB ROM (or 8 MB, in the case of the Game Boy Color).

Game Paks can include a real-time clock and an external battery along with SRAM to hold saves, although all of these are optional.

Types of cartridges

Due to the two modes of operation the Game Boy Color supported, Nintendo listed three different types of Game Boy games:

- Game Boy: A type fully compatible with all Game Boy models. It always runs in DMG mode.

- Game Boy Color enhanced: A hybrid that runs differently depending on the host console. While fully compatible with the monochrome model, it will be visually enhanced (due to running in CGB mode) when running on the Game Boy Color. However, the overall functionality will still be constrained to maintain compatibility with the Game Boy.

- Game Boy Color exclusive: Only compatible with the Game Boy Color, but it takes full advantage of its hardware.

External communications

For the first time, games can communicate with other Game Boys using a Game Boy Link cable, which provides multiplayer functionality, for instance. The interface relies on a very primitive type of serial connection.

The original Game Boy transfers information at 8 Kbit/second (1 KB/sec), while the Color variant may reach up to 512 Kbit/second (64 KB/sec), the latter speed was known as ‘high speed’ mode.

The latter variant is also bundled with an Infrared emitter and receiver (made of an LED and a phototransistor, respectively) [17]. This made it possible to exchange data wirelessly between Game Boy Colors, as seen in games like Pokemon Gold and similar. However, you will find that the system doesn’t implement any communication protocol, only a single register (RP) that encodes the IR sensor’s action (emit or receive), the single bit (0 or 1) being transferred and the last bit received. Nevertheless, to alleviate things for developers, Nintendo did include a reference implementation in the official Game Boy Developer manual [18].

Anti-piracy

As you’ve seen in the ‘Operating System’ section, the console will never run a game right away, it first executes a series of checks that prevent the execution of unauthorised cartridges and also makes sure the cartridge is correctly inserted.

To be able to pass these checks, games had to include a copy of Nintendo’s logo (in the form of tiles) in its ROM header [19], this way Nintendo could make use of Copyright and Trademark laws to control the distribution. Pretty clever, huh?

Conversely, Sega v. Accolade later awarded any company with the right to use copyrighted logos for this kind of requirement, as it falls under fair use.

That being said, more anti-piracy measures can be implemented inside games, like checking the SRAM size (it’s normally bigger in Bootlegs) and checksumming the ROM at random points of the game.